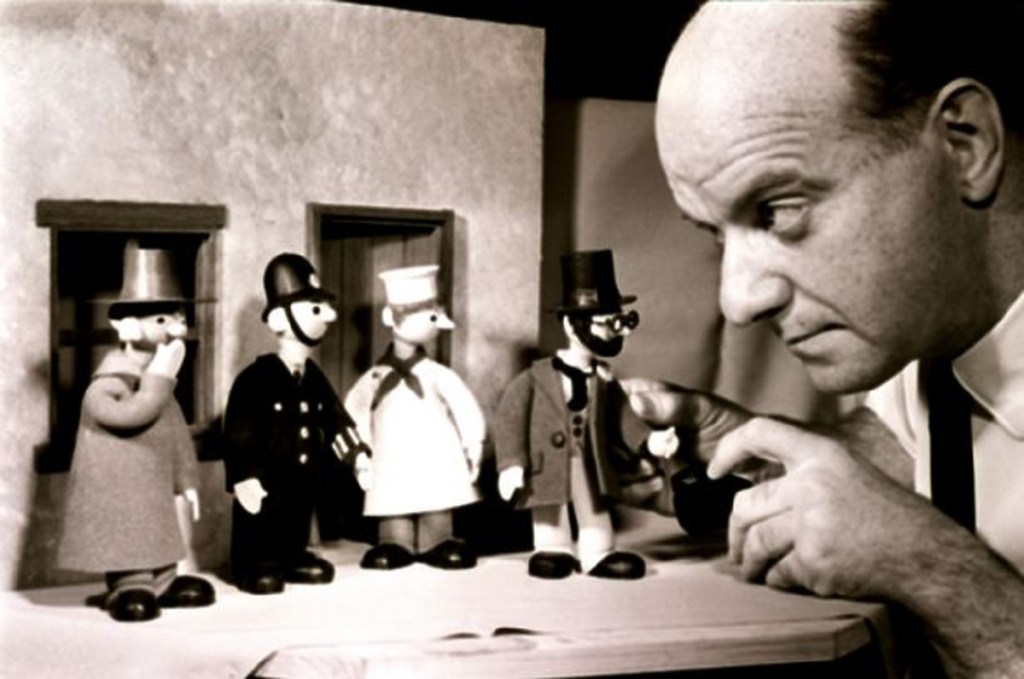

Although viewers of a certain age and indeed the mothers who were doing the watching with them will have been aware of his smart military bearing and somewhat impractically dimensioned moustache for over a month by that point – and you can find much more about that first ever showing of the first ever episode and why anyone who saw it then will have to all intents and purposes have been watching an entirely different programme to the rest of us here – Captain Snort made his first appearance popping up in and out of the Camberwick Green Music Box as part of the BBC’s Watch With Mother strand on 7th February 1966. Although such influences were almost certainly some way down Freddie Phillips’ list of musical references to say the least, it is nonetheless striking just how closely Captain Snort’s sturdily paradiddled introductory song, complete with brisk ahead-of-the-beat guitar chords and call-and-response toy trumpet salutations and indeed affirmation that he was in scarlet and gold a soldier man who lives in Pippin Fort, resembles the sort of psychedelic nursery rhyme-styled character studies that the likes of The Move, The Beatles, Pink Floyd and slightly more notoriously David Bowie would very shortly begin to bother the pop charts with. It is probably fair to say that this similarity was more a byproduct of wider overarching cultural trends and concerns than of John Lennon saying “we should just copy that thing with the Clown, only with more backwards”, but what makes Freddie Phillips’ inadvertent excursion into the world of Uncle Arthur, Three Jolly Little Dwarves and Lucifer Sam all the more remarkable is that it was most likely written and recorded some time around the spring of 1965. For context this would have been more or less while The Beatles were busy doing reshoots for Help!, David Bowie and The Manish Boys were performing I Pity The Fool on BBC2’s Gadzooks! It’s All Happening, Pink Floyd were still called The Tea Set and improvising extended versions of Louie Louie with a conspicuous lack of exclamation marks, and The Move were still ambling around as members of Carl Wayne And The Vikings, Mike Sheridan And The Nightriders and The Mayfair Set with only the faintest of inklings that pooling their Beat Boom out-evolving resources to do a song about the green and purple lights affecting your sight might be a sound career move. He may well not have been quite the psychedelic visionary that this extraordinary quirk of timing might suggest, but Freddie Phillips’ career is nonetheless as a fascinating one for entirely different reasons; as is the story of the making of Camberwick Green, Trumpton and Chigley themselves which, in an intentional channelling of Mr. Dagenham’s ability to sell anything anything anything money can buy, you can read much more about in The Golden Age Of Children’s TV here.

Far less open to cultural conjecture, however, is the influence that the music heard with welcome repetition in the assorted Trumptonshire shows had on successive generations of creatives and people ‘remembering’ stuff in restaurants alike and on musicians in particular, whether directly and contemporaneously as was – apparently – the case with Jimi Hendrix, or in a more diffuse and indirect sense on the likes of Blur as they looked back to the popular cultural totems of their childhoods in order to forge a ‘new’ identity to push forward with as a response to outright aesthetic hostility. If you have no idea of what I may be referencing here and why, and assuming that you have already acquainted yourself with my thoughts on the matter in Looks Unfamiliar here, then you can find features on both of the above in this Mr. Brackett-paced stroll through the archives alongside a look at where you can find similarly much better than it has any right to be music from children’s television programmes in the BBC Records And Tapes back catalogue as well as Emma Burnell on Looks Unfamiliar, which does at least include a look at a storybook with a markedly similar mid-sixties pop art character study aesthetic to its illustrations – so we can actually forge some semblance of a vague thematic conceptual unity for once – and if you want to defy Damon Albarn’s anti-materialistic disdain for all matters ‘Meal Deal’, if you felt dropping by at the Blur-plagued service station and buying me a coffee here it would be very much appreciated. Though that all said, we will actually be kicking off this archival ramble with something of an altogether different tone, partially concerning the unsung genius who conjured up Trumptonshire in the first place…

There is probably little point in relitigating just how rotten a year 2016 was, and how many good people lost – and indeed how many good people we lost – whilst outright bastards seemed to just keep on flourishing. Although you don’t hear too much about Paul Nuttall these days, do you? Nor indeed his once wildly newsworthy gentlemen’s club, which I still believe should have been called ‘Nuttall Men’. This was written late one evening late in that miserable twelve month stretch as I sat waiting for a delayed train and had the misfortune to have The News forced into my awareness unbidden, which provoked this eruption of deeply emotive fury in which I tried to make sense of the frankly increasingly nonsensical present by immersing myself in something that I did understand – the late autumn of 1965, and the inescapable fact that no matter what authority figures might delude themselves into believing, they will never inspire public affection in a manner that popular cultural, remembered or forgotten, will. It was initially a very long and probably wildly unpunctuated social media status that several people begged me to publish as a proper post, so I did. Looking back now it feels more informed by hope than despair, which I now realise was probably my unwitting intention all along. You can find All Dead, But Still Alive here.

Looks Unfamiliar: Emma Burnell – They’re Only Eating Macaroni

Recorded on the day after Boxing Day, which caused Emma to warn me that it had ‘better bloody work as a hangover cure’, this was a welcome return for one of Looks Unfamiliar‘s most popular guests, which despite also featuring psychedelically-tinged children’s storybook The Royal Potwasher and the frustration engendered by evenings spent trying to figure out The Lords Of Midnight on the ZX Spectrum, soon diverted into the endlessly fathomable thrills of late-night pre-Internet student slackerdom spent watching small-hours imported sitcoms on Channel 4 and prank-calling absurdly formatted radio stations. What was even better still, it suddenly emerged mid-conversation that Emma had sung on the unused theme song for ITV’s undistinguished Tiswas replacement The Saturday Show whilst Big Daddy was still pencilled in as the presenter; the opportunity to finally solve a longstanding Saturday Morning mystery was too good to pass up and this formed the basis of a mini-episode in its own right. Yes, she can still remember the lyrics – one of which was exactly what I’d always guessed it must have been – but I would wager that this was the most of any interest that anyone has had to say about The Saturday Show since 1984. Also, if you don’t know where the show title comes from, please don’t Google it. You can find the full show here and the chat about Melody Radio in a collection of Looks Unfamiliar highlights here.

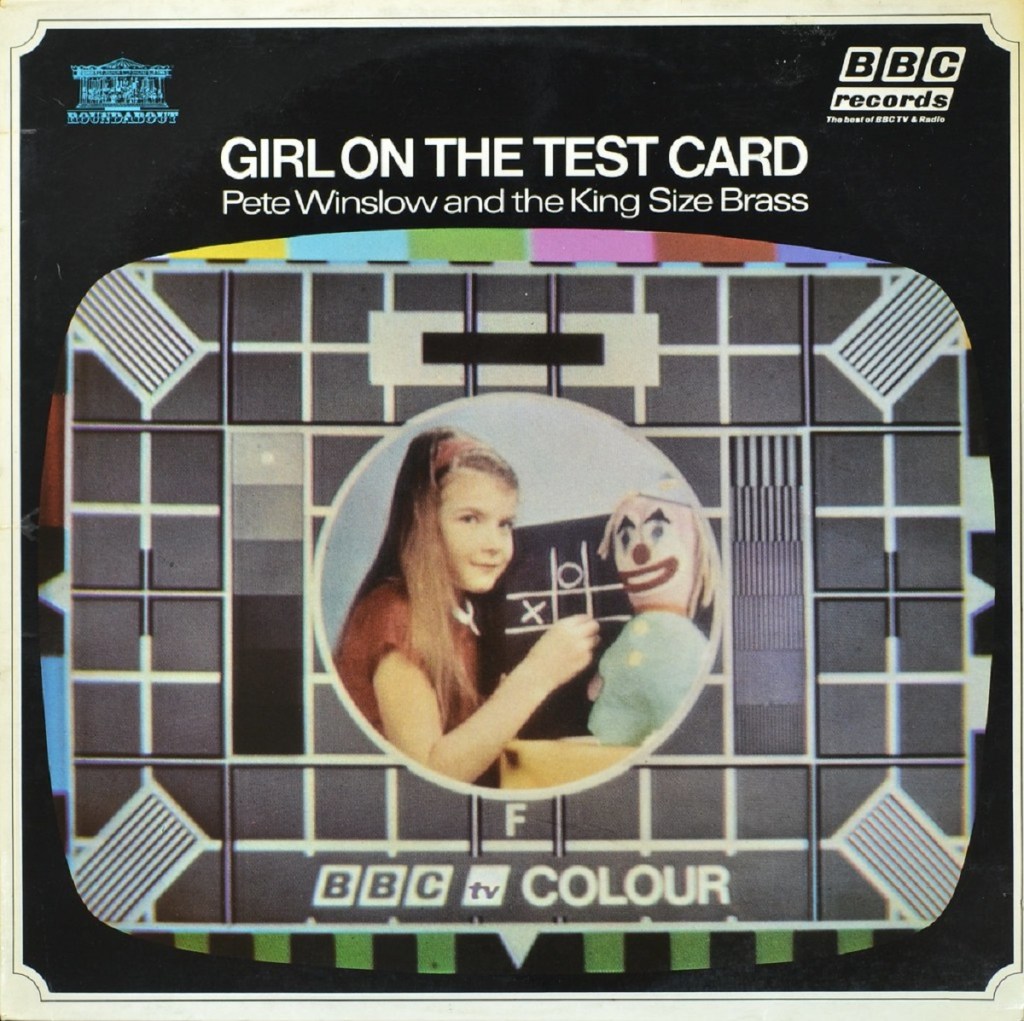

This ‘sleevenote’-accompanied playlist of funky, folky and hard rocking highlights from the BBC Records And Tapes catalogue – taking in juvenile Salvation Army members with a handful of guitar effect pedals, the Play Away team trying their hand at pastiche Blaxploitation soundtrack music, Maggie Henderson retelling a bible story with full-on Stax swagger, assorted BBC Radiophonic Workshop members terrifying late night Radio 1 listeners and some slow-burning stoner jazz recorded to accompany TV’s ‘Clown’ and ‘Girl’ – was put together specifically to promote Top Of The Box, the story behind every single released by BBC Records And Tapes (which in the interests of promotion you can find more about here). Most of the featured tracks were in fact drawn from albums, but at that point I had absolutely no interest in writing a companion volume looking at the label’s long players, which I considered a venture which frankly gave the distinct impression of being an act of wilful madness. How that would change. I was genuinely surprised at how well this went down – it even led to an extrapolated version appearing as a feature in Mojo – which I suppose just goes to show that nobody ever really thinks to look for hidden highlights in the BBC’s admittedly eccentric in-house record label. The title, incidentally, was a play on The Purple Gang’s splendid 1967 single Granny Takes A Trip, which in turn was inspired by the legendary psychedelic King’s Road boutique of the same name. You didn’t get THAT with Yorkshire Television Music Ltd. You can listen to Auntie Takes A Trip here.

Considering how fond I am both of the song itself and – well, fond isn’t quite the word – of the purported inspiration, Kathy Etchingham’s anecdote about Jimi Hendrix supposedly being inspired to write The Wind Cries Mary by a row with her and a chance sighting of BBC Test Card F had long been one of my favourite ‘facts’ to recount, until one day I realised almost entirely by chance that he could not possibly have seen Test Card F before writing and recording the song even if he had been peering through George Hersee’s workshop window at Henry Wood House. Inevitably I wanted to know exactly what he would have been watching, and a quick bit of Charlie Cairoli-anticipating research in fact led me to somewhere unexpected yet all too glaringly obvious. Once again this proved vastly more popular than I had anticipated, although I would also like to note here that while it has since been removed from both the pages for The Wind Cries Mary and BBC Test Card F, this conclusion was once added as ‘fact’ to Wikipedia only with my attribution quickly edited out on the grounds of ‘non-notability’. Worth bearing in mind the next time that they’re badgering you for one pound thirty pence. You can find the original version of The Wind Cries Mickey Murphy here and a massively expanded version with even more research and tons of cultural detours in Can’t Help Thinking About Me here.

For various reasons, despite the popularity of my ruminations on Carole Hersee and Bubbles being hired for a revamped line-up of The Jimi Hendrix Experience, I had not entered the New Year in the most positive of frames of mind, and as always reached directly for something that always seems to shake me out of moments of despond – Starshaped, a tour film that accidentally captures Blur unloved and unwanted with huge unexplained ‘inconsistencies’ in their finances and on the verge of being dropped by their record label and somehow, while shuttling dejectedly around European festival dates and spilling constant cups of tea en route, finding a new-found fire and determination and inventing a radical alternative to everything else ‘alternative’ around them and insisting to anyone who will listen that they are right and everyone else will see what they are on about eventually. In particular, there is one moment where they are talking to a journalist who does not quite seem to understand who they are or why they are there when you can pretty much see their expressions and attitudes change mid-sentence. Although its publication would prove to have something of a bittersweet element, my attempts to express the profound effect that Starshaped holds for me in words certainly worked for me. What I was not expecting, however, was just how much it would work for others. Food Processors Are Great! clocked up forty thousand views in less than twenty four hours and also drew a thank you message from Damon Albarn, which I have to admit I would not have expected whilst endlessly relistening to the b-sides of Chemical World back in 1993. You can find the original version of Food Processors Are Great! here and an expanded version with much more about what Blur’s actual fans were up to around the time of Starshaped in Keep Left, Swipe Right here.

If you consider yourself very much here for the mid-sixties proliferation of TV ‘Clowns’ rather than the first stirrings of Britpop, then you will find plenty to enjoy in Not On Your Telly, available in paperback here or from the Kindle Store here.

Mystery Link! If you want to just go straight to a surprise page completely unrelated to any of the above, click here.

© Tim Worthington.

Please don’t copy this only with more italics and exclamation marks.