Although – and you will win absolutely no prizes whatsoever for surmising this – the wild and outrageous yet genuinely dangerous story of the UK’s leading countercultural magazine Oz, which despite being more or less put together on some borrowed tables in a glorified squat somehow briefly became a national talking point with huge cultural and social influence even before the editors were fitted up on obscenity charges, is a longstanding obsession of mine, this overview of the associated obscenity trial was originally written as a personal response to the aftermath of the terrorist attack on the offices of Charlie Hebdo in 2015, and the ensuing attempts by numerous bad faith actors from all corners of the political spectrum to manipulate the global public reaction to their ideological advantage. I would probably have reworked this and reused it as more of a direct feature about Oz itself and the ferociously yet aimlessly censorious atmosphere of the early seventies and the endless demands that an indefinable ‘something’ must be done about an equally indefinable ‘it’, except, well, with absolutely no reference to any current news story whatsoever your honour… the central tenor of the original piece doesn’t get any less relevant, does it? Some wags and indeed some who depressingly appeared to be entirely serious did send scoffing rejoinders that Oz did indeed sometimes feature material that while quantifiably not obscene by legal standards – and those standards have actually relaxed since the early seventies – would certainly be considered unacceptable nowadays. Well, of course it did and I am well aware of that – for a start I have deliberately avoided using a couple of more pertinent illustrative images here for that exact reason – but it doesn’t really change anything about the background of the ‘Schoolkids Issue’ and the trial itself, they did also at the same time champion a number of progressive causes including influential support for gay rights, and the last time I checked, you were actually still allowed to be interested in something without that necessarily constituting an automatic legally binding endorsement of any and every aspect of it. Incidentally, speaking of not necessarily endorsing any and every aspect of it, I seem to have somehow omitted to mention John and Yoko’s bizarre cacophony of a protest single that probably didn’t help very much God Save Oz, but rather than describing it myself I’ll refer you instead to the fascinating chat about it in The Big Beatles Sort Out here. Incidentally you can find a longer version of “Am I Waking You Up?”, with a good deal more on the wider public response to the Oz trial, in Can’t Help Thinking About Me, available in paperback here or from the Kindle Store here.

On 21st June 1971, three young men were dragged before a court over a cartoon.

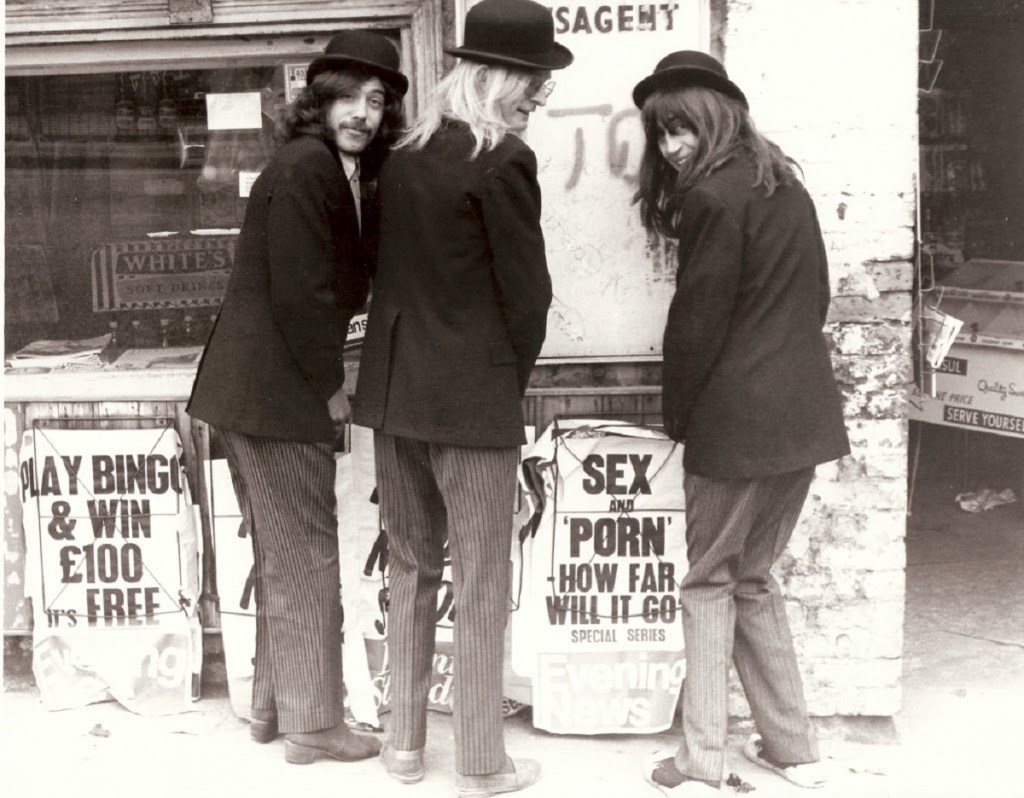

This was the trial on obscenity charges and conspiracy to deprave and corrupt of the editors of Oz, a dazzlingly-designed countercultural arts and lifestyle magazine, which over the past couple of years had outgrown its hippies-in-a-squat publishing origins to become a high street-rivalling must-read, and this trial of its editors was essentially the establishment’s long-awaited revenge on everything that had irked them about the decade of satire, psychedelia and free love. From those young ruffians making fun of our sacred institutions in Beyond The Fringe, through modern art and moves towards sexual and racial equality, to any last utterance by any given Beatle and probably even the opening titles of Zokko!, Oz editors Richard Neville, Jim Anderson and Felix Dennis were effectively being made to stand trial for the sociocultural ‘crimes’ of an entire generation. It was as though the flustered gentleman who had only recently barked at a David Frost-baiting Dennis on live television that he ought to spend more time near a cenotaph had suddenly been given the keys to the Old Bailey. In case you are not unreasonably thinking that this is all a load of paranoid conclusion-jumping educated guesswork by someone who wasn’t even born at the time, I can honestly assure you that it is not, and that the above was made proudly and gleefully explicit in pretty much every utterance by the prosecution and, most notably, presiding judge Justice Michael Argyle. Not being backwards in coming forwards was clearly one of the values that the establishment still held dear.

For the benefit of anyone who’s unfamiliar with the background to the trial, in May 1970 the Oz editors had given over an issue to up-and-coming still-at-school aspirant contributors and named it ‘Schoolkids Oz’. This was far from an unusual move – in the past they had run women-only and even gay-only issues; you can bet they’d wanted to prosecute over that – and the resultant top-drawer material included early efforts from iconoclastic rock journalist Charles Shaar Murray, design critic Deyan Sudjic, publisher Trudi Braun and veteran foreign correspondent Peter Popham. However, the in-retrospect perhaps ill-advised retitling gave the authorities a long-awaited chance to arrest and charge the editors, on the pretence that they believed that it was an issue intended for sale to schoolchildren. Key in their artillery of material liable to deprave and corrupted the supposed army of innocent young minds it was not intended for was a cartoon by Vivan Berger – which you can see in full here – depicting Rupert Bear as a priapic degenerate launching himself at generously-proportioned ladies. Although it’s easy to see why this would have caused unease back in 1970 – and, lest we forget, Rupert was of course the star of a long-running comic strip in the not exactly free thinking Daily Express – with hindsight it’s also possible to appreciate it as an irreverent note-perfect subversion of the mind-numbingly repetitive layout and language of the original cartoons. But were the guardians of our national morals going to listen to that back in 1970? Were they fu[NEE NAW NE NAW etc]

Plenty of people did try to make a stand, though, and in a peculiar way the repercussions still reverberate today. The Policeman’s Jig, a scathing rejoinder to the Oz controversy and also to the recent seizure of prints of Andy Warhol’s Flesh from the rarely so politicised Jake Thackray, was mysteriously shelved by EMI and would not see release for another three decades, while Michael Palin’s published diaries reveal his tangible exasperation at having attended a dinner party full of educated, articulate people who refused to accept any argument against the obscenity charges or in defence of the editors, even from someone who only weeks beforehand had been locked in a fierce dispute with the BBC over Monty Python’s notorious ‘Undertaker’ sketch. Many of them duly turned out in force to speak in defence of the editors, but found their efforts belittled, dismissed or ignored by the judge.

A list of public figures who had allowed themselves to be identified as regular readers, ranging from David Frost to Daily Mail columnist Paul Johnson – “hardly a pillar of the permissive community”, as defence counsel John Mortimer noted to much amusement – was met with a threat to clear the court if the jury continued to display reaction. Vivian Berger’s brave taking of the stand was prefaced with a warning that he was “technically an accomplice”. DJ John Peel, eloquently defending Charles Shaar Murray’s references to ‘fuck music’ with well-researched historical detail, was forced with some reluctance to talk about his recent fronting of an awareness campaign about sexually transmitted diseases, and then upbraided by the judge for bringing the issue up despite the fact that he hadn’t; Edward De Bono, one of the most prominent theoreticians of the late Twentieth Century, was reduced in the summing up to “a gentleman from Malta”; activist and broadcaster Caroline Coon was introduced with remarks that, if they were made today, she may even have been able to take legal action over; artist, jazz musician and film critic George Melly grew so irate with the high-handed disapproving discussion of his defence of the word ‘cunt’ that he volunteered that “I might certainly refer to a politician as one”; and leading psychotherapist Josephine Klein was asked “so we have no children of our own?”.

They met their match, however, from a most unexpected direction. Comedian Marty Feldman, at that point still best known to most people as the star of his own off-the-wall BBC2 show of a couple of years previously – so a move roughly equatable to getting Peter Serafinowicz to appear as a key defence witness now – began his evidence by refusing to swear on The Bible because “there are more obscene things in that book than in any issue of Oz“. Over the course of a barnstorming appearance he bluntly swatted aside any and every impassioned and overwrought whimper from the prosecution with hefty and witty counterdoses of reality and logic, and became visibly agitated when he reminded the court that “in a dictatorship, one of the first things that they try to do is to outlaw ridicule”; as child of wartime Jewish immigrants he might well have had some awareness of what happened the last time that people started burning books. When Argyle disingenuously attempted to wave away Feldman’s forceful and impassioned evidence by claiming not to be able to hear him, the comic smartly rounded on the ageing gavel-wielder and asked “am I waking you up?”.

Marty Feldman’s appearance probably did more than anything else to ensure that the jury delivered a guilty verdict, albeit on lesser charges than those originally brought, and that the judge handed down the most draconian sentence – including enforced haircuts – that he permissibly could, but it also, crucially, did a great deal to win over the hearts and minds of the general public. Suddenly these three foul-mouthed long-haired layabouts were the underdogs persecuted by the old, the posh, the rich and the out-of-touch, and few things seem to stir up the populace to quite the same extent; even some of the right-wing tabloids considered the haircuts a bit much. So great was the outcry that within weeks, an appeal hearing accepted that the jury had been grossly misdirected and overturned the convictions. The three editors were once again free in the outside world, where conventional mainstream media careers beckoned for both them and for the ‘Schoolkids’. Well played, The Establishment.

At the start of the trial, John Mortimer had remarked to the jury that the case stood “at the crossroads of our liberty, at the boundaries of our freedom to think and draw and write what we please”, and, depressingly, that’s exactly where we find ourselves yet again. This is why this is not just a straightforward everyday piece about the Oz trial, and why I’m not concluding by recommending some of Deyan Sudjic’s books, or remarking on Felix Dennis’ remarkable retaining of his charitable countercultural values while moving in big business and high society, or even how Charles Shaar Murray’s sustained attacks on the lacklustre solo careers and slipshod yet pedestal-mounted repackages of the same old material did more to undermine The Beatles than any tweedy letter to The Times ever managed. Instead it’s ending with a plea. Never forget, never lose sight of the fact that censorship and opposition to freedom of expression comes in many forms and can hide anywhere. There are people out there that will use the recent senseless brutality over another cartoon to try and hoodwink us into accepting their own curbs on liberty. They will want you to take sides, to believe in a handy off the shelf threat, to accept that their way of tackling things will keep everyone ‘safe’, more often than not for no other reason than, somewhere along the line, their own personal gain; they want you to be, essentially, Michael Palin’s dinner companions.

Don’t let them.

Buy A Book!

You can find an expanded version of “Am I Waking You Up?”, with much more on the background to the Oz trial, in Can’t Help Thinking About Me, a collection of columns and features with a personal twist. Can’t Help Thinking About Me is available in paperback here or from the Kindle Store here.

Alternately, if you’re just feeling generous, you can buy me a coffee here. Yes, hippies, that’s me hassling someone for ‘bread’.

Further Reading

There’s a look at what else frequent visitor to the Oz offices Vivian Stanshall was up to early in 1971 in The Road To Rawlinson End here.

Further Listening

Regular Oz reader David Bowie released a single called Holy Holy while strange events were unfolding at the Old Bailey, so how come it’s almost entirely disappeared from his discography? Find out here!

© Tim Worthington.

Please don’t copy this only with more italics and exclamation marks.