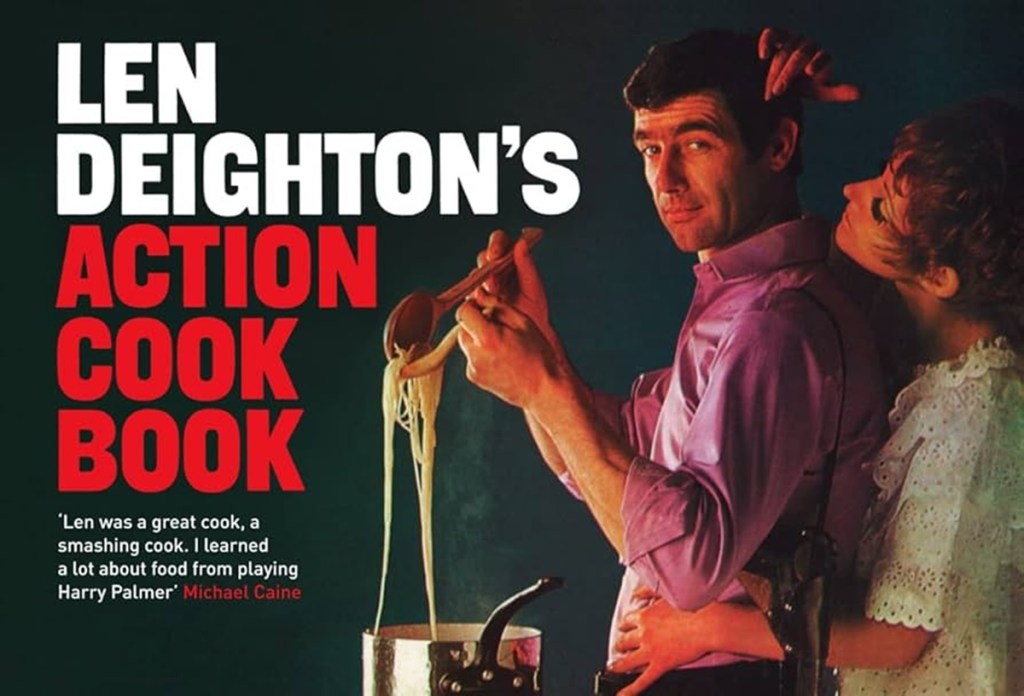

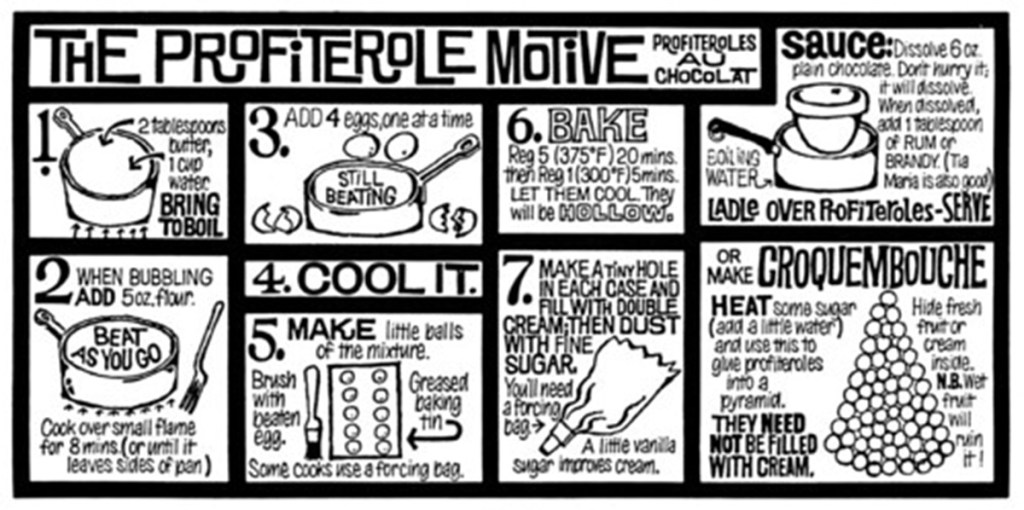

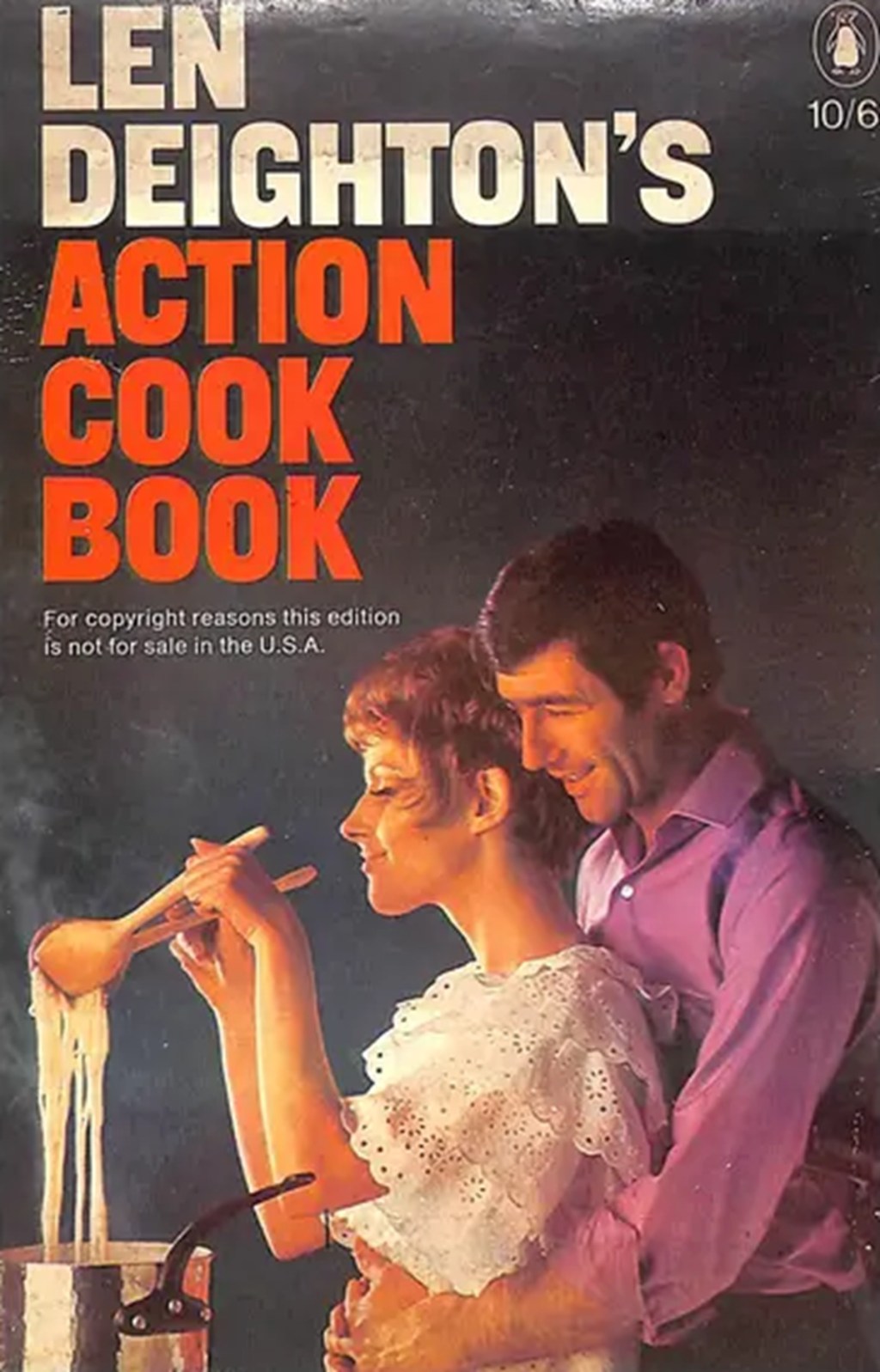

First published by Jonathan Cape in 1965, Len Deighton’s Action Cookbook is a collection of ‘cookstrips’ – or highly stylised comic book-styled graphical renditions of sophisticated twists on straightforward recipes – that the one-time chef at the Royal Festival Hall had originally created to assist him with rattling through preparing dishes for the benefit of patrons struck by sudden pangs of ravenousness on their way to see the latest André Marchal recital. After being spotted by the Daily Express‘ design editor Raymond Hawkey, a couple of the strips found their way into the paper before moving with Hawkey to The Observer‘s newly launched colour supplement, where they would run as a weekly fixture between March 1962 and August 1966. Although the quietly macho undertone that characterised the collected cookstrips could potentially be considered moderately ‘problematic’ from a modern perspective, as indeed could possibly even some of the food itself, to disregard them for that reason would be to the considerable detriment of the positive impact that Len Deighton’s Action Cookbook had in a decade that was still only gradually inching away from the societal expectations of the Post-War Consensus. Vibrant and witty, the cookstrips encouraged young men with a James Bond fixation to get their hands if not dirty then at least herby and immerse themselves in a prospective leisure pursuit that had previously been very much considered little other than an unrewarding duty for the lady of the house, in an encouraging manner that emphasised both the sense of personal achievement and gratification and the likely beneficial impact on your social standing that transforming yourself into an aspirant Michelin Star-recipient could present. Len Deighton himself perhaps did not find himself similarly rewarded for this quiet instigation of a gradual culinary revolution, but it is possible he was not unduly concerned about this; between the launch of the cookstrips and their collation in handy paperback form, he had written his very first best-seller in the form of hugely topical espionage thriller The IPCRESS File. Its central protagonist – ‘hero’ might be pushing it slightly – was a down at heel and decidedly unglamorous geezer-about-town turned secret agent who very evidently had more than a few cookstrips pinned to the corner of the bedroom that also served as his kitchen wall; Harry Palmer. Who of course was never directly named in the original series of novels, but we’re getting a little ahead of ourselves there.

A whole three decades later, a new monthly magazine aimed specifically at cornering a birthday gifted aftershave-scented gap in the market attempted to reintroduce a degree of the aesthetic and ethos of Len Deighton’s cookstrips into a world that had moved forward as much as it had moved back. Although it would eventually become clear what its core readership really wanted – or indeed what they really really wanted – and the admittedly never exactly not-present pop stars and children’s television presenters in their bra and pants quotient would be sharply upped to an ultimately overwhelming degree, Loaded in its initial iteration strove hard to educate and inform as well as eroticise, and accessibly-toned features on science, literature and cinematic classics and indeed how to rustle up a deceptively impressive main course came packed densely around the Elizabeth Hurley photoshoots, while early noted figures of aspiration included Peter Cook, Chris Morris and Damon Albarn, and in a surprising break from ‘tradition’ the likes of Jo Brand and Donna MacPhail were presented as hilarious comics with scorching live shows rather than set to one side with the expected not remotely suspicious masculine dismissal that while you are not sexist, you just do not find women funny, not for any reason or anything, you just don’t because you don’t. Key to Loaded‘s intended original aesthetic were a string of films Michael Caine had made in the sixties and early seventies, and in particular a loose trilogy in which his interpretation of the authority disrespecting, convention despising, culturally open-minded, gastronomically enthusiastic and ‘bird’-respecting – well, by the standards of the day at least – Harry Palmer was so vividly realised that it became as good as impossible to read the original novels without hearing them in his voice. Even the one that they never got around to making a film of.

Whatever sentiment – if that is the appropriate word – Loaded may have engendered in the longer term, one of the many overlooked positive aspects of its admittedly complicated legacy was its championing and rediscovery of aspects of popular culture that through their ephemeral nature and lack of elevated critical acceptance had long since fallen into disregard. Or in the case of those Michael Caine films, fallen into the very furthest reaches of the BBC’s television schedules, where in the days when television actually still used to close down overnight it was standard practice to sign off before the globe, the National Anthem and the Test Card with an otherwise overlooked film that attracted a small but fervent audience of those who were permitted to ‘stay up’ to watch it and an even larger and more fervent audience of those who pleaded to be allowed to do so. From portmanteau horror and ‘Swinging London’ comedies to sleazy seventies detectives and sprawling surrealist satire, the BBC1 ‘late film’ – as memorably denoted with a continuity slide showing some film cans swathed in differently-coloured lights to present the tacit illusion that they were both ‘red hot’ and ‘blue’ – was a guarantee of a very different kind of quality to the one that those who would seek to bore you senseless with their own personal interpretation of Truffaut’s deployment of mise-en-scène as if they had somehow entirely missed the fact that À Bout de Souffle is a belting thriller with breathtaking location work and amusingly knowing pop culture references would expect from their critically acclaimed minimalist dramas featuring just the eighty four minutes of long silences. For reasons that are neither entirely clear nor comprehensible, however, those eight Michael Caine outings in particular gravitated towards the outer reaches of the schedules in the week leading up to Christmas, wherein they would frequently appear in various orders and permutations last thing at night on BBC1, with the onset of the unofficial mini-season invariably marked by Radio Times with a single italicised line at the foot of the first film’s billing reading ‘Michael Caine appears in Pulp on Tuesday’. So whisk yourself a quick Ludovic’s Focaccia, put down that Anna Friel interview and resist however many hours of Penn And Teller – Don’t Try This At Home Channel 4 are attempting to lure you away with, as we take a look back at the escapades on either side of the law of Jack Carter, Charlie Croker, Michael Finsbury and company – not to mention the accompanying and suitably sharp cinematography, fashions and soundtracks – as if you were catching them on rolling in after a work or social festive do in that frosty hinterland of the last few difficult to locate doors on the advent calendar. I suppose you think you’re going to see the bleedin’ titles now. Well, you all settled in? Right, we can begin. His name is…

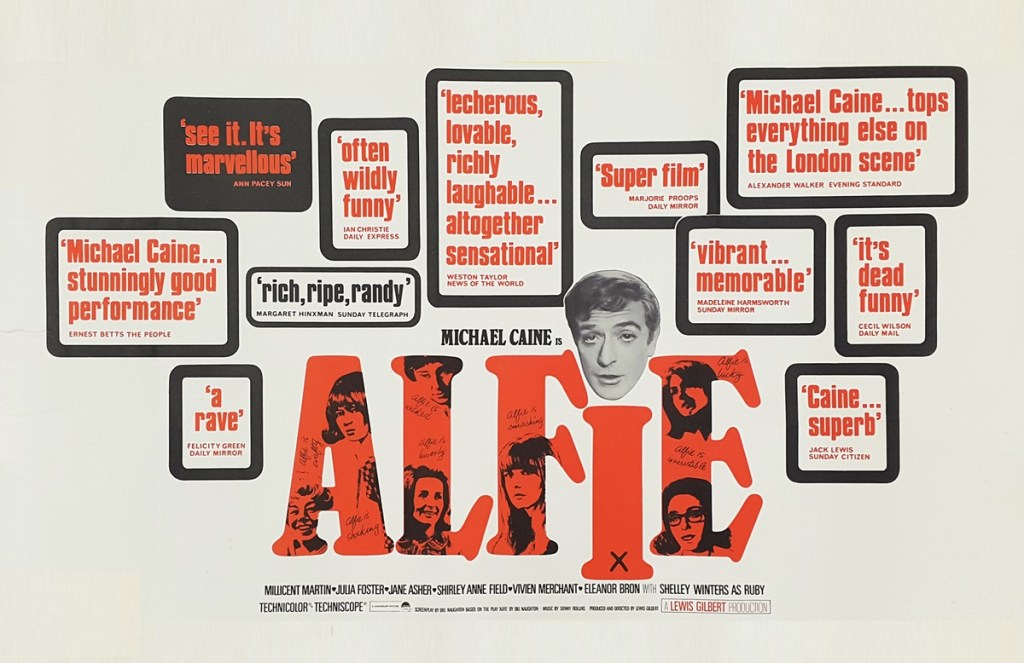

Alfie (1966)

Alfie Elkins, a young chauffeur at large in a London just about displaying the first tentative creaking signs of ‘Swinging’, has it all. At least that’s what his friends – and many, many lovers – think. Does he actually have what he wants, though – or is everyone else living vicariously through him?

Like so many of the mid-sixties social commentary comedies it once routinely shared the last thing at night on BBC1 timeslot with – most notoriously The Knack… And How To Get It – Alfie is a film that poses a distinct and difficult problem from a present day perspective. Although it addresses some challenging issues in a firmly progressive manner for the time, and at least approaches those that are arguably less progressive with a wry consideration of both sides of the experience, it is nonetheless weighed down by one dominant aspect that appears off-puttingly jarring to modern audiences – in this instance, Alfie’s insistence when addressing the camera on referring to women as ‘it’. While this is unquestionably important to his character in relation to his need to shut himself off emotionally, and in a neat touch subtly softens during the third act, it and indeed ‘it’ has taken on so much additional negative social and cultural baggage since Alfie was originally made that you could honestly understand anyone making a face value dismissal of the entire film as misogynistic drivel on that basis. Without making any attempt to excuse the now uneasy dialogue as a product of its times, however, it is still worth looking past that to consider Alfie as a whole in its original context. It has a surprisingly highbrow background, originally presented as a play on the BBC Third Programme – a radio station so serious in tone and artistically refined that it made its eventual successor Radio 3 look Radio 1 in the middle of Thirty One Days In May – that drew so much critical praise that it was rapidly repeated, before being staged at the celebratedly actorly Mermaid Theatre, requiring delicate negotiation with the Lord Chamberlain’s Office to obtain permission to depict some of the more contentious for the time aspects of the plot.

There is no denying that the big-screen adaptation of Alfie plays up the humorous and bawdy aspects considerably, but ultimately the central thrust of the narrative remains exactly the same – no matter how envied or enabled Alfie’s lifestyle may be by others, it proves detrimental to his physical health, deleterious to his mental health and a much-resented barrier to the genuine opportunities for happiness that come his way; or, as he puts it himself in the final scene, “I’ve got a bob or two, some decent clothes, a car, I’ve got me health back and I ain’t attached… but I ain’t got me peace of mind – and if you ain’t got that, you ain’t got nothing. I dunno. It seems to me if they ain’t got you one way they’ve got you another. So what’s the answer? That’s what I keep asking myself – what’s it all about?”. Caught between who he could be and who others expect him to be, Alfie may be damagingly emotionally unavailable but is never manipulative – rather it is certain of his deceitful and controlling ‘respectable’ associates of both genders who emerge as the relative villains of the piece – and for better or worse is always both aware of and affected by the consequences of his actions. In an intentional move by director Lewis Gilbert, many of the roles of the women that Alfie regards so casually are filled by actresses who were making a very clear name for themselves in traditionally ‘male’ fields, including Millicent Martin, Jane Asher, Eleanor Bron and Pauline Boty. Most significantly, however, there is the subplot about a backstreet abortion – it would be almost a full two years after the release of Alfie that the Abortion Act 1967 fully came into effect – which tellingly is devoid of the drama and turmoil and even ominosity that characterised similar depictions around this time. Instead it is framed as something approaching an everyday inevitability for two characters who have been left with no viable alternative, not to mention a bored and impatient illegal practitioner, and it does not shy away from showing the subsequent emotional impact on Lily and in turn on Alfie; and in a shocking move for the time, the film only very narrowly shies away from showing the actual ensuing physical mess it has left in its wake. It is grim, depressing and undramatic but in no way judgemental – it is simply a relatively graphic depiction of something that at time time was happening everywhere but spoken about nowhere, and it is difficult to think of a more powerful counterpart in a similarly widely-loved mid-sixties comedy film. He does say ‘it’ a lot, though.

Capturing what is on the very verge of becoming ‘Swinging’ London but is thronging with people, buildings and establishments that are taking their time in moving with the times, Michael Caine’s to-camera asides may be far from revolutionary but the manner in which he treats the audience as a possibly judgemental co-conspirator rather than just sharing exposition or a joke genuinely does feel like a fresh approach for fresh times, as indeed do the frequent deployment of dramatic rather than comic cutaways and the stylish credits using photos of the cast in lieu of the traditional text captions. Sonny Rollins’ moody jazz score underlines the sense that the entire film is pitched somewhere between carefree abandon and careful caution, although it is probably best not to go in to the incessantly confusing proliferation of different edits with different renditions of the title song; although I did make at least some attempt at this here if you’re interested. Yet for all of its wit and visual verve, Alfie would be a spectacularly downbeat note to conclude your evening’s viewing on, especially in the week leading up to Christmas, if it wasn’t for Michael Caine’s deft combination of charm and depth, making someone who would now be an eminently cancellable character into one who remains widely loved and recognised. It’s probably best not to dwell on that remake, however. Let alone Alfie Darling…

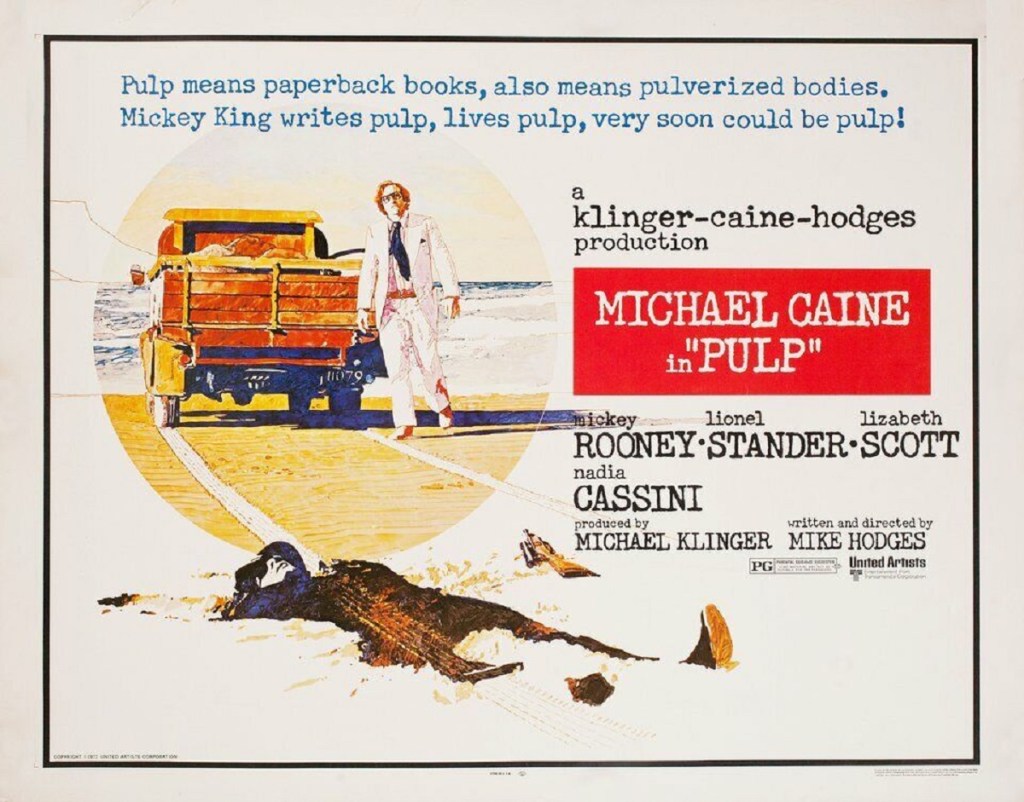

Pulp (1972)

Mickey King is a prolific author of lurid paperback thrillers enjoying the high life – and the tax breaks – in Malta, until he is asked to ghostwrite the autobiography of a mysterious faded Hollywood star and finds himself drawn into a conspiracy so wild and violent that it very nearly makes his books look respectable…

In some regards, it really does feel like Pulp is having its prinjolata and eating it. It wasn’t just Mickey King enjoying the financially unrestrictive high life in the early seventies, and the British film and television industry were awash with co-production funded racy thrillers set in allegedly glamourous semi-exotic and more importantly economically advantageous international locations, thronging with regionally popular co-stars whose participation came as part of the deal and ‘furnished’, as the credits always had it, with motor vehicles, speedboats and light aircraft provided by local manufacturers, with the imperative to include anything resembling an actual storyline very much lowest on the list of considerations. From The Marseille Contract and Shatter on the big screen to The Adventurer and The Protectors if you elected to save your money and stay at home, audiences had little respite from maverick lawmakers and lawbreakers living it up in a world of fish courses and exotic lager labels and already flimsy pretexts for a plot that tended to get forgotten about from about two thirds of the way in until the big waterfront punch-up at the end anyway, much of which traded in a queasy blend of high living European glamour and what can only be described as a just about tolerated degree of mild sleaze; and although it’s unquestionably one of the more likeable examples of the artform, you can find further thoughts on this phenomenon and the reasons behind it in a look at the 1974 ITV series The Zoo Gang here. In this context, having the central character of Pulp lounging around in Malta churning out transcription service-shocking smut whilst saving a couple of extra pence here and there could almost be taken as a wry tongue-in-cheek comment on the entire audience-testing setup if it too didn’t also abandon any semblance of narrative development at more or less the exact same point. Although Pulp looks fantastic, as indeed does Michael Caine in his safari jacket and impractically overdesigned sunglasses – even if his extremely early seventies hairstyle does lend the impression that he is about to start demanding green jelly from Rich and Stew at any given moment – it is almost a decade on from The IPCRESS File and that sense of lean tautness and sharp dressing in austere surroundings is basically nowhere to be seen.

That said, Pulp is a movie directed by Mike Hodges and starring Michael Caine, so no matter how much it may wander off into wandering towards the conclusion, it is told and presented with wit and flair throughout. The ‘blue’ content is similarly wryly handled with a knowing grin never far away from any given mock-obscene reference, most gloriously in a scene where some locals holding placards find themselves repositioned by the action to inadvertently spell out an amusingly reactive ‘F**K’. While there admittedly is a lot of expositionary dialogue in boring-looking rooms, Pulp adopts an imaginative narrative structure that not only veers between the real-time on-screen storyline and Mickey King’s narration, but even in that narration careers around live commentary, retrospective summary and attempts at working it all into putative new fiction, and punctuates all of this with ‘overheard’ snatches of other characters’ thoughts, quasi-illusionary sound effects and cutaways to battered old clips of illustrative film. The plot in itself is quite grim, and Mickey Rooney is so good as the vain and deluded faded star with a dark past that you could scarcely describe him as likeable, but the inventive approach is what elevates Pulp way beyond the lazy stylistic traps that it could so easily have fallen into. A little like a certain band who would later borrow its name and indeed a good deal of its aesthetic, in fact.

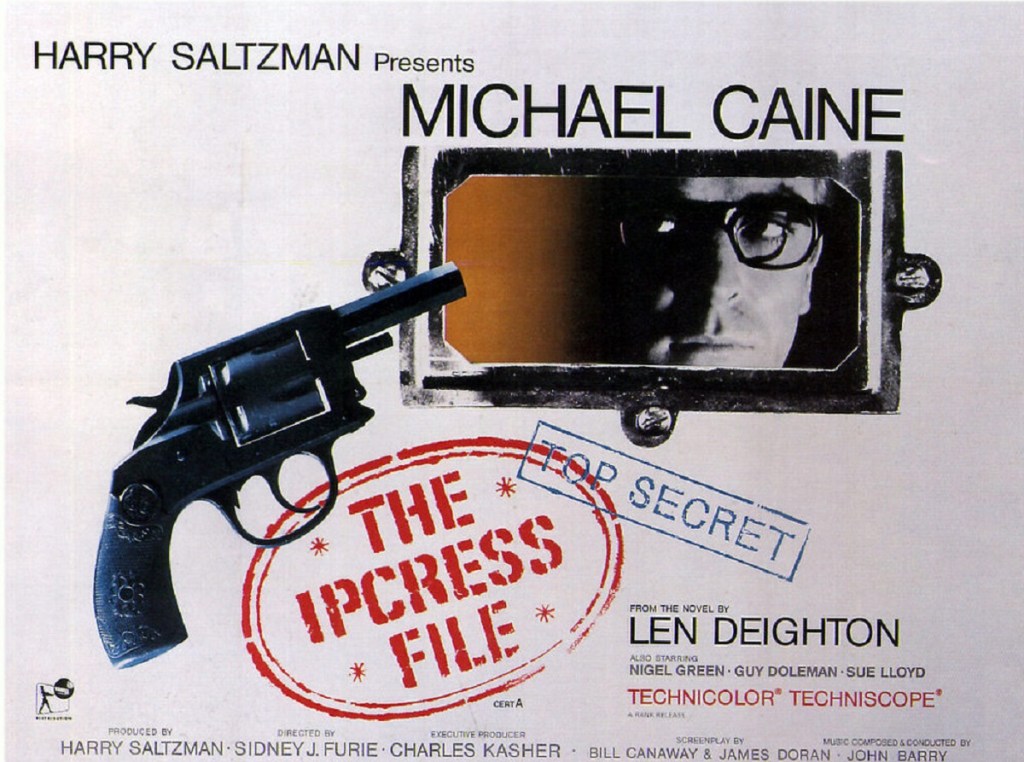

The IPCRESS File (1965)

‘Persuaded’ to join the Intelligence Service when his sideline in smuggling contraband back and forth across the Iron Curtain was rumbled, former British Army Sergeant Harry Palmer is becoming exasperated both with his haughty superiors and his dull surveillance duties when he stumbles across a fragment of audiotape with a weird electronic noise on it, a whole two years before The Beatles recorded Carnival Of Light…

Originally published late in 1962, The IPCRESS File was an instant international best-seller and it is not difficult to see why. In a world that was becoming increasingly fixated on exotic jetsetting glamour, Len Deighton’s narrator – originally deliberately unnamed in the early stages of the novel to subtly reinforce his position as an outsider, before Deighton astutely decided that there was no real narrative benefit to suddenly introducing him formally three quarters of the way through – is a modestly if sharply attired jack the lad forced against his better judgement into a world of pipe smoke, desktop decanters and former public schoolboys who had never quite left their alma mater. In an intentional contrast to the approach favoured by detective fiction at the time, Deighton kept the narrative loose and chaotic but anchored around a single self-evident conspiracy to be uncovered rather than a mystery to be solved; it was the getting from suspicion to proof in the face of continual attempts by double-double-crossing conspirators, co-conspirators and counter-conspirators to silence him metaphorically and literally at every turn that proved more of an obstacle than straightforward ruminating over clues. The stakes were high, with the storyline centred around a Cold War paranoia-charged plot to brainwash scientists and public figures into defecting – which in an alarming coincidence, would prove shortly after publication to be an unnervingly topical concern – but the mechanisms at work behind the conspiracy were as low-tech and mundane as they come. The interpolation of ciphered messages, carefully worded official communications and chapter headings cryptically presented as horoscopes lent more than a suggestion that this was something that the likes of you were very much not amongst the eyes that it was only for, but the narrator’s lack of class pretensions and perpetual awareness that – much like the reader – he had found himself if not exactly out of his depth then certainly in a world he could do little to influence brought proceedings right back to the everyday and ordinary. It has all the drama, glamour and action of a wet Thursday afternoon in central London without a bus in sight, and is ironically all the more exciting for it.

The IPCRESS File both streamlines and condenses the plot of the original novel – which involved various overseas excursions where the on-screen action scarcely ventures further than the Science Museum Library in South Kensington – and reduces both the number of characters and subplots. In an even more malevolent twist, the brainwashees are all scientists who are being conditioned to simply abandon their research and retire, and the climax ratchets up the edge-of-the-seat tension and paranoia where the novel had more or less concluded with a couple of firmly shut filing cabinets. All of which play their not inconsiderable part in building up a film that rarely seems to score less than one hundred percent in aggregated reviews, but few would dispute that the most important element is the downtrodden but fine living character at the centre of it all. With the possible exception of electing to give him a name – purportedly inspired partly by a dull classmate of Caine’s and partly by the lack of nomenclatural glamour suggested by producer Harry Saltzman, which he was reportedly mildly less than amused by – Sidney J. Furie and Michael Caine’s masterstroke with the big-screen adaptation of The IPCRESS File was to play up the aspects of the protagonist’s personality which were simultaneously relatable and aspirational to an audience that had scant idea of the different between shaken and stirred in the first instance, let alone whether they should make any difference. For a full three minutes and two seconds under the opening credits, in a cramped flat with the detritus from the previous evening’s shared bottle of wine still taking up his work surfaces – and a cookstrip showing how to achieve the perfect braise pinned up on the side of a cupboard – Harry Palmer is seen silently and methodically making a cafetiere’s worth of fresh ground coffee before circling a handful of likely runners in that day’s runners at Hamilton Park, smartening up his suit and casually concealing his pistol about his person. In an unexpected encounter in the supermarket, he is sarcastically berated as ‘quite the gourmet’ by his handler Colonel Ross for favouring exotic ‘foreign’ ingredients over homegrown canned produce a whole 10d – or seventy three pence in old money – cheaper. When his fellow agent Jean Courtney ‘casually’ drops by to conduct an assessment of him on behalf of Major Dalby, the main points in her report are that he enjoys ‘books, music and cooking’, apparently marking him out sufficiently as an anomaly in the Intelligence Service. Although she is initially resistant to his in-progress meticulously-prepared Denver Omelette – with the chopping and whisking provided in seamless close-up by Len Deighton himself – and his choice of Mozart as ‘music to cook by’, a smitten Harry eventually wins Jean over not by showing off but through open and adult conversation, in particular when he both asks about and listens to her difficult experiences as a young widow in a thankless profession. None of which may well sound like very much at all now, but their success in putting such qualities across against a bleak and threadbare backdrop of a London that even then had still not quite finished rebuilding itself really does mark it out amongst more or less any and every other film of the era.

That said, even Michael Caine’s expertly judged performance could not quite have carried The IPCRESS File without one other remarkable element. Engaged to provide the soundtrack on account of his work on the James Bond franchise – which it is worth remembering was a whole three instalments in at the time – but asked to make his score – which you can find more about here – as unlike Bond as possible, John Barry set aside the huge orchestras and twangy electric guitars and reached instead for the cimbalom, an Eastern European instrument essentially resembling a strummable coffee table, and furnished the on-screen action with an eerie and downbeat accompaniment that acted as a disquieting echo of the tacit awareness that the Cold War was haunting you wherever you went. Meanwhile, the loop of brainwashing sounds created by sound engineer Norman Wanstall is all the more convincing and unnerving for the fact that there is no attempt to make it outlandish or unworldly – it is simply a collection of swoops, klaxons and beeps as if you had somehow got caught between rooms in a tour of a lightbulb-in-red-cage era research facility. Hopefully no viewers found themselves subliminally persuaded to abandon their research into the controversial science of who they still hadn’t got presents for yet, but The IPCRESS File, as acclaimed on release as it still is today, proved to be ideal for the timeslot it had somehow found itself in – and it was one where Harry Palmer would make himself very comfortable indeed.

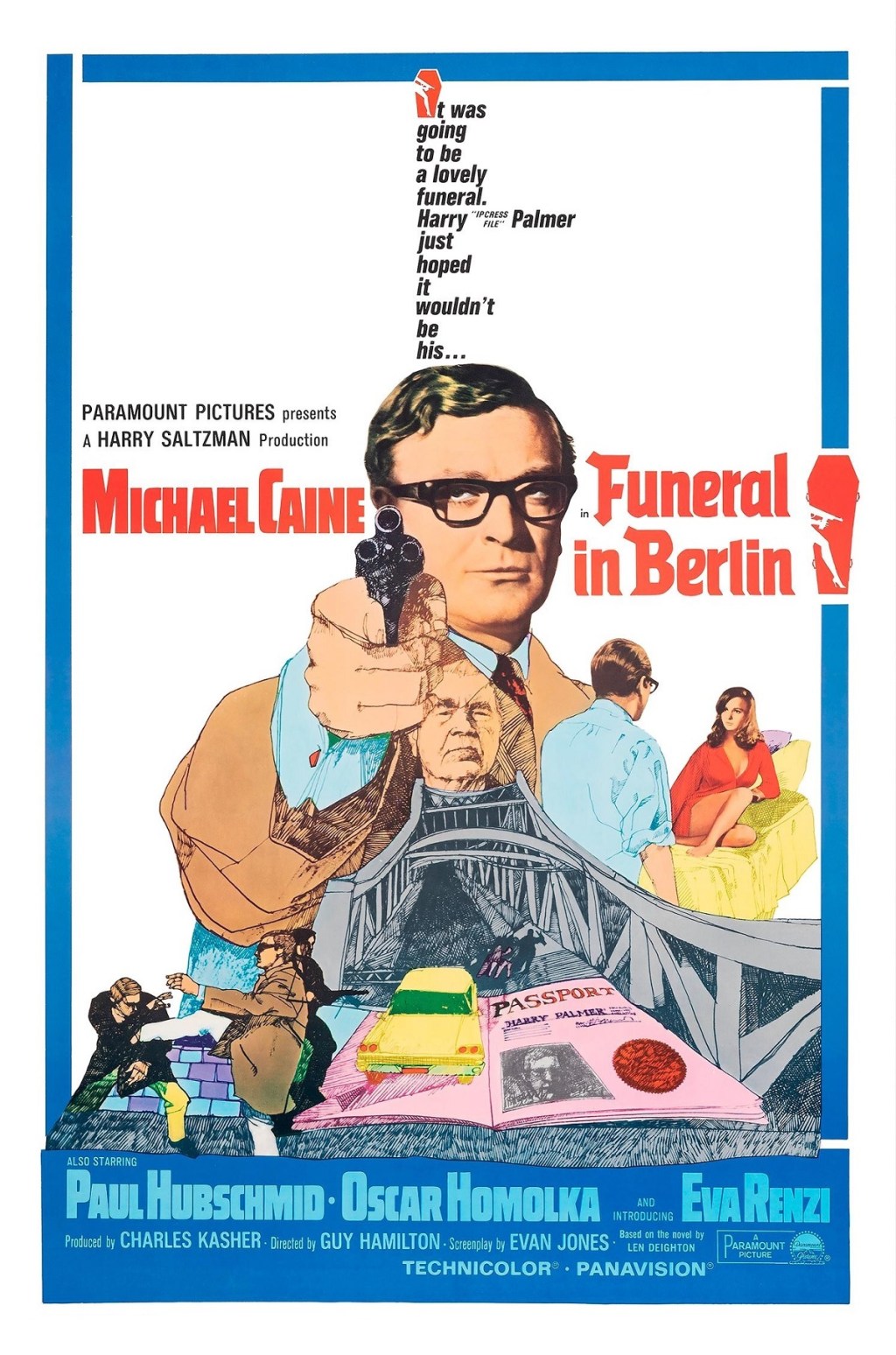

Funeral In Berlin (1966)

Harry Palmer finds himself back in the shadow of the Berlin Wall, assigned to facilitate the defection of a high-ranking Soviet Intelligence Officer – and doubtless pick up the ingredients for a first class sauerbraten while he’s at it – but he can’t help feeling that everything seems to be going just that little bit too smoothly on either side of Checkpoint Charlie…

Len Deighton’s second Harry Palmer novel was in fact 1963’s Horse Under Water, in which unknown parties are racing against the British Intelligence Service to get their deep sea diver-gloved hands on a sunken U-Boat off the coast of Portugal which is variously believed to contain a fortune in forged currency, a submarine-sinking quantity of heroin and a list of Third Reich-endorsing double-agents known to still be at large. Matters only become more complicated still when some experimental ‘ice melting’ technology enters proceedings, but if you are wondering how they managed to interpret this effectively on the big screen, the answer is that they didn’t. Whether on account of the complexity and cost, uneasiness surrounding the importance of the literal ‘horse’ to the storyline or the fact that MGM had recently acquired the rights to Alistair MacLean’s superficially similar 1963 novel Ice Station Zebra – the eventual 1968 movie becoming yet another longstanding and much-loved occupant of the BBC1 late night film slot, and again often seen around Christmas and New Year – Paramount perhaps wisely elected to swerve the unswervable hunk of metal stranded on the sea bed although then again seemingly so did everyone else; as far as can be ascertained, there has not been a single adaptation of Horse Under Water. It hasn’t even been read on Radio 4’s A Book At Bedtime. Although even if it had been, most of its probable audience would most likely have been watching Harry Palmer on television instead.

Funeral In Berlin followed in 1964, and in all honesty was probably a better fit from a thematic point of view anyway. With many of the cast of The IPCRESS File reprising their roles and an introductory scene with Harry and his oversized shirt-sporting new girlfriend sharing some of his meticulously made coffee while listening to the BBC Third Programme, it essentially picks up directly from the conclusion of the previous film and while it is generally regarded as something of a comedown after the spectacular highs of The IPCRESS File – although in fairness it would have been difficult for pretty much anything they tried to quite match that, let alone an overambitious bash at Horse Under Water – there is still a refreshing and well-judged shift in tone that would certainly lead some to consider it their favourite, if not necessarily the ‘best’, of the three. Much of the physical threat is replaced by a forbidding paper trail to be literally deciphered, and with some form of business as usual having resumed there is a higher degree of levity amongst the rest of the characters which Palmer’s mordant wit – the that The IPCRESS File came to an actual gag was his repeated droll affectionate acknowledgement of General Ross’ frequently self-professed yet mysteriously elusive ‘sense of humour’ – fits into remarkably well. The overall aesthetic of Funeral In Berlin is a lighter tone in starker surroundings, and to be honest surroundings did not as a rule come starker than this.

Remarkably filmed in the actual locations presented – albeit occasionally disrupted by large camera glare-provoking mirrors whenever they looked like they were capturing too much military detail for the East German authorities’ comfort – Funeral In Berlin now stands as a remarkable if bleak document of a time when Germany was literally bisected by a big barbed wire-topped concrete wall. Constructed in August 1961, it was still a troubling new literal barrier to peace when Funeral In Berlin entered production. on 9th November 1989 it was demolished as quickly as it had appeared, as the commencement of the reunification process gave eager residents licence to knock it to the ground with whatever they had to hand. By the time that Loaded were running two page features on Len Deighton, it was already a distant memory. What is remarkable from a present day perspective is just how sharply the scenes set around the wall contrast with those shot in West and East Berlin; the former not quite ‘Swinging’ but more progressive than London was in 1966 and very much a city on the move, the latter more sparse but with surprising splashes of colour and vibrancy in amongst the rows and rows of shopfront functionality. Most staggeringly of all, the opening sequence sees a defecting concert pianist – “they probably paid him to leave” muses Harry on hearing his playing – is swung across the wall in a builders’ bucket on a crane and evades the border guards on foot, much of which is impressively rendered in a continuous take and so convincingly done that you do have to wonder how it did not end up causing an international incident. They were not just there to capture documentary footage, though, and the complex storyline which really does require the viewer to pay attention in a good way is brilliantly handled by a superb cast led by Eva Renzi as a Mossad operative – there is a whole subplot about her hunt for a Nazi war criminal and the risk that Palmer’s activities might present an obstacle – Hugh Burden as a shifty forger and a staggering turn from Oskar Homolka as Colonel Stok, the defecting Russian whose eccentric boozy demeanour cannot deter Palmer’s suspicion that he is perpetually one step ahead of everyone else. It is somehow simultaneously of a piece with The IPCRESS File yet also entirely distinct from it, but while that may have worked brilliantly late at night on BBC1 decades later, back in 1966 it may have given the producers entirely the wrong idea about where to go next…

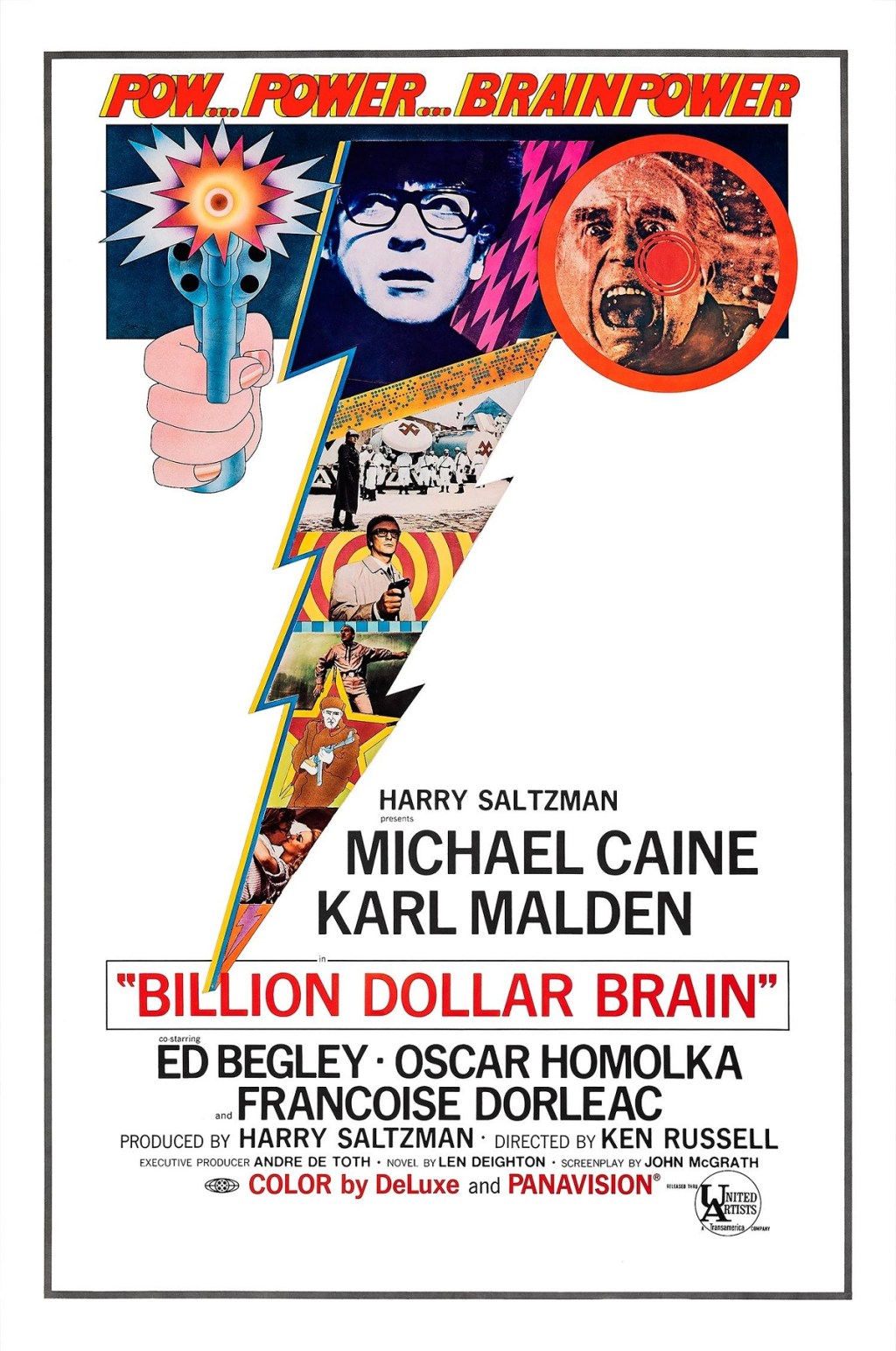

Billion Dollar Brain (1967)

‘Retired’ from the Intelligence Service and trying to set himself up as a private investigator, Harry Palmer receives a phone call from an automated voice instructing him to take some weaponised virus samples ‘borrowed’ from Porton Down to Helsinki or else; and when a rogue American military man with a private army, a big bleeping supercomputer and an old ‘friend’ – well, sort of – enter the fray, he probably finds himself as confused as anyone looking at a Radio Times listing and trying to work out whether it’s worth setting the video or not.

First published late in 1966, Billion-Dollar Brain was effectively the last of Len Deighton’s series of novels featuring the unnamed narrator commonly referred to as Harry Palmer; or at least it was until the character possibly resurfaced in the third person in 1967’s An Expensive Place To Die, potentially reappeared with a different name in 1974’s Spy Story, and unquestionably returned in the almost completely forgotten Yesterday’s Spy in 1975 and Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Spy in 1976. The following year, the unhyphenated Billion Dollar Brain became the last of Michael Caine’s series of films starring as Harry Palmer; or at least it was until he returned to the role for Bullet To Beijing and Midnight In Saint Petersburg, a pair of deservedly tepidly received television movies from 1995 which featured no input from Len Deighton whatsoever and which Michael Caine, in a rare move, publically distanced himself from. It is probably fair to say that they both have their moments, but they are literally just moments. There was also a little-seen film based on Spy Story in 1976, starring Michael Petrovich as ‘Patrick Armstrong’ alongside Derren Nesbitt as Colonel Stok and such surprising names further down the cast list as Tessa Wyatt, Nigel Plaskitt and Nicholas Parsons. Spy Story itself did occasionally show up last thing at night on BBC1, but the fact that it never appeared alongside the other Harry Palmer films is perhaps all that really needs to be said about it. Billion Dollar Brain, of course, would routinely appear in daily succession after The IPCRESS File and Funeral In Berlin, though in itself it does not perhaps lend itself to as coherent an unofficial trilogy as everyone involved might have hoped.

Billion Dollar Brain is everything you would want from a late sixties Cold War thriller directed by Ken Russell. Unfortunately, however, it is not really what you would want from a Harry Palmer film. From the opening scene, where Harry’s office is not just liberally decorated with pin-ups of naked women and boxes of cornflakes but overlooking a brightly lit corner of Swinging London thronging with well-to-do nightlife, it is obvious that the original appeal of the character has been woefully misjudged to no appreciable benefit and for no readily obvious reason, and it is fair to say that relegating Colonel Ross to an exasperated feed for incredibly weak jokes does not exactly help. That said, Michael Caine is not about to allow that to prevent him from presenting the script he has been handed in the characterisation he considers appropriate, and he is fortunate to be surrounded by a cast similarly determined to make the movie work, notably Ed Begley’s genuinely terrifyingly unhinged interpretation of the crazed General Midwinter, whose incoherent yet forcefully expressed rant about how modern society has devalued ‘love’ when it should mean patriotism and patriotism alone – well, apart from the ‘love’ he simultaneously appears to express for the members of his private army – is honestly not too distantly removed from the average babbling gibberish belched out round the clock on present day news outlets, and a welcome return for Colonel Stok whose belligerence is not especially subtly tempered by his awareness that he owes his freedom and indeed his life to Harry Palmer. Otherwise there are some unlikely directorial choices – notably flash cutaways to ice hockey violence and Klan rally conflagrations – that seem especially at odds with the understated realism of Funeral In Berlin in particular, and the overall impression is that a slightly incorrect version of Harry Palmer is adrift in a world he does not belong him; an impression that is not helped by flashy psychedelic womanising-implying Bond-on-the-cheap opening titles, although it has to be said that Richard Rodney Bennett’s rarely acknowledged main title theme really is up there with John Barry’s best efforts. Even the ‘supercomputer’ itself, a Honeywell H200 as used in thousands of businesses across the globe at that point and operated on screen in accordance with the actual technical manual, looks too slick and streamlined to be especially visually interesting from this distance. Interestingly, Billion Dollar Brain shares a great deal in common with The General, an episode of The Prisoner featuring a much more traditionally ‘futuristic’ computer, and while it is tempting to speculate on which was copying which, they in fact both appeared within days of each other. Clearly the thought of punch cards had been keeping Patrick McGoohan up at night too. Michael Caine would later generously remark that Ken Russell had done everything right with Billion Dollar Brain apart from explaining the plot clearly enough, but even that is still skirting the issue that it is both a huge comedown after and too just about perceptibly different from the two earlier Harry Palmer films. No wonder they abandoned a vague plan to follow it with poor old Horse Under Water. Not that you would especially have objected to seeing it at twenty five past eleven on 19th December, though.

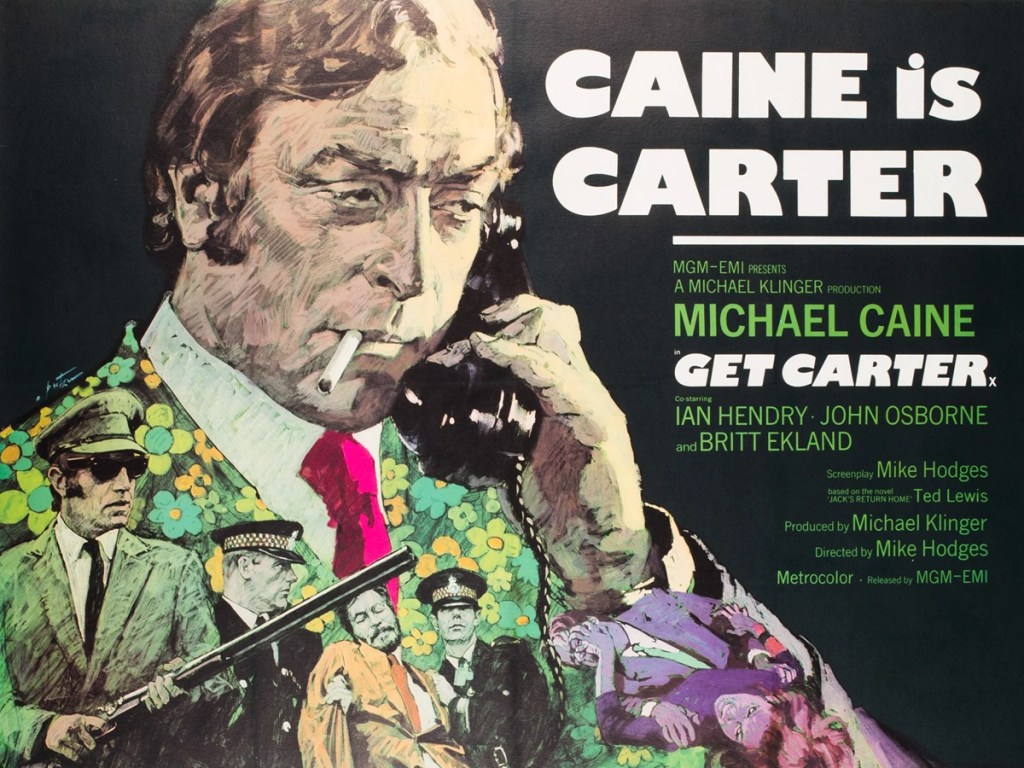

Get Carter (1971)

East End gangster Jack Carter is on his way back up North for his brother’s funeral, but can’t help feeling that something about the purported drink-driving incident doesn’t add up; his London paymasters don’t want him asking questions that might harm their ‘legitimate business’ interests, and the Newcastle mob don’t want him asking questions full stop, and the truth is even murkier than the bedsheets hanging out in everyone’s back alleyways…

From working as an animator on Yellow Submarine and crafting corny gags for BBC1’s late sixties Saturday morning show Zokko! to having his proposed Doctor Who script The Doppelgangers rejected at a late stage after – depending on who you believe – arriving drunk to a production meeting, it is fair to say Ted Lewis was an erratic talent with a chequered career to say the least. Although his novels invariably sold well, his only major success was the 1970 gangland thriller Jack’s Return Home, and even that has since been overshadowed by – and indeed will now set you back a small fortune second hand because of – a big-screen adaptation that followed in short order, and which the majority of people who have seen it probably do not even realise was based on a novel in the first place. Beset by financial setbacks from the outset, Get Carter would succeed in repositioning its reduced circumstances into a virtue. Director and scriptwriter Mike Hodges had impressed the producers with his work on a string of recent television hits including Tube-hopping prog-soundtracked museum-robbing children’s thriller The Tyrant King and determinedly grimy ITV Playhouse offerings Suspect and Rumour, and was eager to make an impact with his big-screen debut. Jazz musician turned soundtrack composer Roy Budd was barely a couple of months into his new career, and had come straight from working with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra on the sharply controversial Solider Blue to a budget that covered a handful of days in Olympic Studios at the outside. His solution was to bring in bassist Jeff Clyne and percussionist Chris Karan from his jazz ensemble while he himself played piano, harpsichord and electric piano, improvising much of the music around a recurring fifteen-note motif in response to early edits of the on-screen action. Meanwhile Michael Caine may have been at the height of his star power, but had begun to feel increasingly uneasy with playing a procession of comic gangsters and when informed of the director’s intention to make a movie that unflinchingly depicted the brutal reality of the consequences of crime he accepted the lower status role virtually sight unseen, even going as far as to suggest that Hodges removed some of Carter’s more likeable traits from the original scripted dialogue. Between them – and despite the pessimistic predictions of many behind the scenes – they created a startlingly grim and unattractive movie that somehow still not only became a commercial and critical success but even had one or two jokes in it.

Get Carter is both geographically and tonally far removed from Harry Palmer’s brow-furrowing over scraps of manilla envelope, but it was made in what may have been only a handful of years later but was otherwise to all intents and purposes a very different time. The giddy vibrancy of mid-sixties excitement and optimism had well and truly swung off its pendulum do, and the headlines were dominated by industrial, civil and territorial unrest as the grim realities of social intolerance and exploitative labour relations began to almost literally bite. Television may now have been in colour, but the world outside that rectangular assemblage of 625-line broadcast information was suddenly very short on it. Get Carter was so unremittingly reflective of its time that even late-night television showings were being very heavily trimmed well into the mid-nineties, often removing references to hard drugs that rendered certain key aspects of the climax of the plot unintelligible; it was even cut for its original theatrical release, a decision welcomed by Mike Hodges who felt that the enforced tightening of violent shots made for an even more blunt representation of the reality of unglamourised violence. That all said, it was a film made to entertain as much as it was to shock, and there is no shortage of mirthless yet hilarious gags delivered with suitably curt unawareness. Carter is to some degree a sympathetic character but it is a sympathy that can only extend so far, and the stark absence of emotion in the somehow expected yet also unexpected final shot is so rare amongst films of this type that it is not difficult to understand why Michael Caine was so keen to make it. To the audience he is all the more striking as a mediocre-overcoated hardened brutal killer moving freely and unobtrusively amongst the ‘ordinary’ people, yet to those ‘ordinary’ people in the film itself he is a figure of suspicion tainted by lah di dah fancy London ways and a stranger on his home turf, with his request for a pint of bitter ‘in a thin glass’ and open reading of Raymond Chandler’s Farewell, My Lovely on the train drawing glares more threatening than any from the underworld figures he has crossed. He is unable to blend in to a changed world of unarousing perfunctory sex, dolled-up women dancing around their handbags in dilapidated nightclubs, majorettes marching around hangover-strewn early morning streets and endless rows of functional shops with even more functional signs, and this is what creates the unsettlingly steady level of background tension that refuses to relent throughout the entire film until suddenly it is just gone.

Although Ted Lewis would revisit the character in Jack Carter’s Law, a 1974 prequel novel set with hilarious incongruity on Christmas Eve and which is well worth tracking down, and the much more elusive Jack Carter And The Mafia Pigeon in 1977, the odd ill-advised remake of varying quality aside, the big screen wisely elected to leave Jack Carter’s exploits at this one astonishing slap to the face of a film and its remarkable soundtrack, which succeeded directly on account of so little being expected from it beforehand and which doubtless left a handful of millions of late-night viewers on 22nd December finding that those few seconds between the abrupt fade and the announcer’s cheerful sign-off over that big ice-sculpted BBC1 ‘1’ seemed to stretch on into infinity, but they probably wouldn’t have had it any other way.

The Wrong Box (1966)

Cousins Michael, Julia, Morris and John Finsbury discover that their respective assorted parents and guardians are the last remaining participants in a tontine – a legal trust that bestows an accumulated fortune on the lucky ‘winner’ – and quickly arrive at their own not necessarily entirely philanthropic conclusions on how the money must be attained, distributed and spent. Some of them it has to be said are more interested in this financial jackpot than others, although it soon transpires that none of them are quite as interested as – apparently – every single other resident of London…

Far from ruminating over potential plot details in a tobacco-fugged villain’s drinker or whilst rustling up a quick Trout a la Meunière with an optional side order of horseradish sauce, Robert Louis Stevenson and his stepson Lloyd Osbourne fine-tuned the wild narrative structure of The Wrong Box during a series of semi-recreational exploratory voyages around the Pacific. Stevenson had originally written an early version of what was at that point known as The Finsbury Tontine in 1887, but felt sufficiently unsure of it to rework it under the title A Game Of Bluff in 1888. It was only following an excursion from San Francisco to neighbouring island groups, and in particular an extended stay in the Hawaiian Islands where they enjoyed a fast friendship with the royal family, that they by all accounts found themselves able to consider the eccentricities of their erstwhile countrymen from enough of a remove to be able to wrest the fiendishly intertwining comic plot into something more satisfactory. Hugely popular on its publication – and raved about by no less an authority than Rudyard Kipling – it would inspire both further collaborations between the two in the more straightforward adventure approach of 1892’s The Wrecker and Ebb Tide in 1894, and astonishingly apparently no known substantial adaptations whatsoever before the BBC Home Service’s now almost entirely forgotten ninety minute 1959 presentation starring Max Adrian and Jane Barrett; lower down in the cast list, incidentally, were Richard Hurndall and Gabriel Woolf, incredibly prolific radio actors in their day but subsequently better if indeed not only now known for prominent appearances in Doctor Who. It is not entirely impossible that the haphazard storyline and enormous ensemble assortment of characters had previously led directors and producers to assume that it was essentially unfilmable. In 1966, however, Columbia Pictures and Bryan Forbes decided to have a go with a cast drawn from the biggest names in British comedy – old and new alike – of the mid-sixties. By the time that production was completed, having fallen so far behind schedule that there was no option but to include shots inadvertently capturing television aerials on the rooves of what were ostensibly Victorian houses, they may well have deemed it essentially unfilmable too.

What makes The Wrong Box so appealing on spotting it hidden away in the outer reaches of the listings in Radio Times – and also what led to me discussing the film on Goon Pod here – is also what the majority of critics will invariably hold up as its most significant flaw; never has the designation ‘all star comedy’ been more chaotically deserved. There are heavyweight actorly veterans Ralph Richardson, Wilfrid Lawson, Cicely Courtneidge and John Mills putting their decades of stage farce experience to bickeringly effective use. There are graduates of the comedy film generation including Irene Handl, John Le Mesurier and Thorley Walters. From fifties radio comedy there are scene-stealing cameos from Tony Hancock as a detective who wants everyone involved to just stop whatever it is they’re doing and go home and Peter Sellers attempting to sign his name with a cat. Then bringing matters right up to the minute, there’s Peter Cook and Dudley Moore. When filming commenced in early September 1965, the first series of Not Only… But Also… had concluded barely sixteen weeks previously, and although a repeat on BBC1 had brought the duo to wider attention in the interim, the first transmission had only been seen by the small percentage of viewers at that point who had the higher definition television sets required to receive BBC2. As popular as they may have been both individually and as a double act since appearing in 1960’s revolutionary stage revue Beyond The Fringe, in comparison to the rest of the cast – even Peter Sellers – they were still effectively young upstarts who could easily have been fading from popularity by the time that The Wrong Box was released. Now of course there is genuinely a case for arguing that they are the most well-remembered names in the entire film. The surrealist brass ensemble The Temperance Seven – a notable precursor to The Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band and company, now almost entirely forgotten despite topping the charts in 1961 with the George Martin-produced You’re Driving Me Crazy – manage to score repeated laughs with the expertly judged stop-start attempts at their constantly interrupted bandstand repertoire, and even the likes of Leonard Rossiter and Nicholas Parsons are impeccably hilarious in their generally wordless split-second cameos as the less fortunate participants in the tontine. Then right at the end, everyone – well, apart from the latter – gets caught up in a wild high-speed frantically John Barry-soundtracked chase using whatever mode of transport is to hand to be the first to stake their claim to the partially promised riches. You might well understandably expect Michael Caine and Nannette Newman to struggle to maintain the comic momentum in such elevated company, but they both display perfect timing and deliver their gags with the right balance struck between sincerity and silliness, especially when they are called on to conduct a conversation via an inconveniently positioned letterbox. There is of course the small matter of how straightforward it may or may not be for the viewer to entirely keep pace with the assorted escapades of this assortment of varyingly degreed-do-wells, but that in all honesty is scarcely the point.

As much as Hailliwell’s Film Guide may have predictably wearily bemoaned that “the excellent period trappings and stray jokes completely overwhelm the plot” as if that was not the entire point even of the original novel, Tony Hancock’s biographers may understandably feel unable to avoid drawing a direct line between his character’s weary disinterest and his own monumental personal and career problems at the time and the non-starting vehicles he was starring in either side of production, and Radio Times reviewers can confidently stamp it ‘moderately amusing in places’ without having to undergo the inconvenience of actually watching it, to anyone who sits down in front of their television last thing at night hoping to see a small army of very funny people wrestling with a script that is constantly on the verge of spiralling way beyond control, The Wrong Box delivers so effectively that it would doubtless cause Morris and John to start alternately punching each other and waltzing in an avalanche of dislodged airborne banknotes. It is far from perfect, and may indeed be found wanting next to the earlier cinematic credits of its headline stars – it’s certainly not I’m Alright Jack, put it that way – it was and remains one of the most impressive examples of what was in all honesty a now completely ignored mid-sixties trend for all-star big-screen escalating farces, and arguably had sufficient a cultural impact to inspire a somewhat more vestmental trend that would in turn inspire a certain popular beat combo to start sporting suspiciously familiar items of turn-of-the-century regalia only a couple of months later. Although it is neither as original or thought-provoking – or indeed as suitable a showcase for their talents – as Peter Cook and Dudley Moore’s gloriously misfiring star vehicle Bedazzled would prove the following year, it certainly delivers and lands more laughs per minute, and is streets ahead of more or less any British comedy film based around a big name of the day from the past quarter of a century, always launched with such ludicrously disproportionate fanfare and arrogant expectation that the audience will ‘love’ it and then quietly and deliberately forgotten about virtually on the morning of release. What is more, where Get Carter may have left those late-night BBC1 viewers stunned and for good and powerful reason, The Wrong Box sends them off to Test Card-avoidance on a much more heartwarming note. Well, unless you’d been rooting for Morris and John rather than Michael and Julia. Even that, though, never quite left viewers on as much of a literal high as a certain other Michael Caine star vehicle; and indeed vehicle…

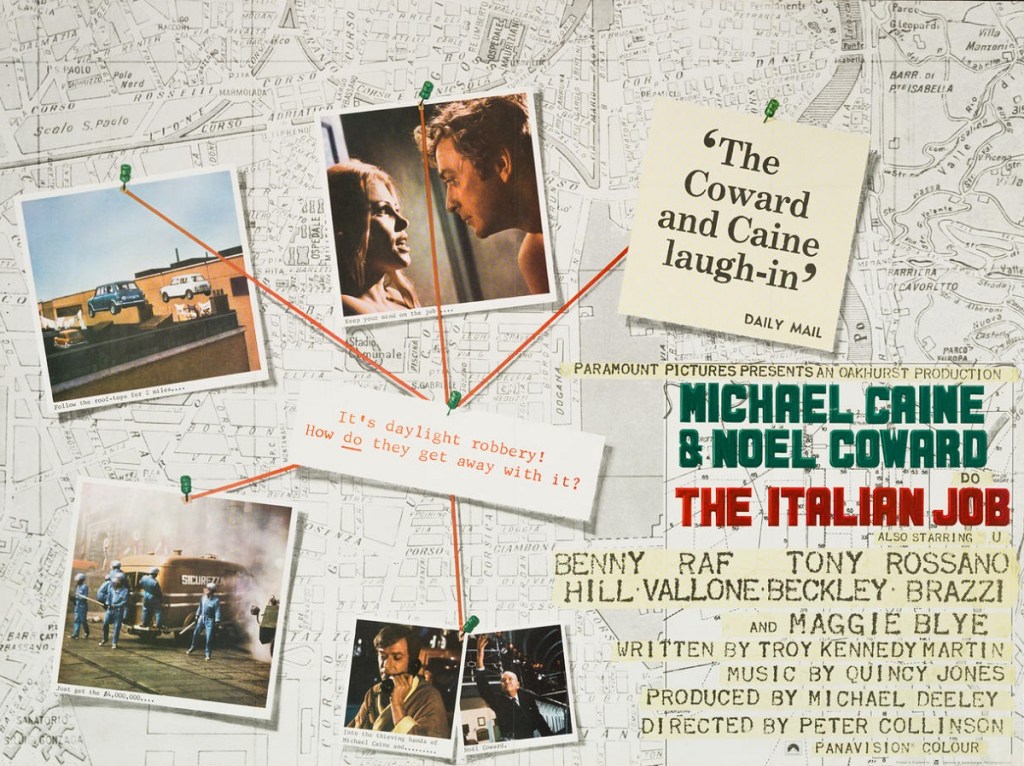

The Italian Job (1969)

Fresh out of chokey – or as he prefers to tell his tailor, back from ‘America’ – small-time crook Charlie Croker is handed a big time job by the family of a master thief who was taken out by the Mafia whilst plotting it. To get a cool four million in gold bullion out of Turin, he’s going to need help from his most disreputable associates, a trio of very fast drivers, an inexhaustible supply of Mini Coopers, a city full of high-spirited football fans and, perhaps most riskily, scrupulously well-mannered crime lord Mr. Bridger. Can they outrun the combined forces of the local constabulary and the equally local organised criminals, or will they find themselves in the most famous – literal – cliffhanger in movie history? Get your skates on, mate…

Aside from only being supposed to blow the bloody doors off – itself only one of dozens upon dozens of sharply written and equally sharply delivered but sadly less quotable one-liners in a script that does not allow a split second to pass without an attendant gag – there is one detail of The Italian Job that more or less everyone is familiar with; namely that it ends with the would-be bullion-purloiners trapped in a coach teetering on the edge of a cliff as Charlie Croker turns to his notably harder-of-thinking co-conspirators and reassures them “Hang on a minute, lads… I’ve got a great idea”. Invariably, every couple of years, some smartypants will come along asking everyone to look at them because they have thought of a ‘solution’ by being cleverer than you at mathematics, science or drama, or even all three. Not only is this arguably an expression of self-serving disrespect for its effectiveness as an ending – something that I had much more to say about here – but it also displays a wilful ignorance of the production of and indeed context surrounding The Italian Job. Writer Troy Kennedy Martin – who, it is worth noting, was the creator of the BBC’s long-running procedural police drama Z-Cars – was steeped in a sixties of low key to the point of almost accidentally successful UK-generated cinematic franchises, one of the most popular of which had of course starred a certain Michael Caine. He had always envisaged The Italian Job as the first in a series of comic escapades for Camp Freddie and company, and in fact had devised several potential solutions intended to open a very much at least amber-lit sequel with. The high production costs combined with a surprising lack of international appeal would see to it that the second instalment of The Italian Job never actually happened, but to date, not one of the ingenious solutions to that cliffhanger have represented any form of a diversion from those devised and proposed by the film’s actual writer back in 1969. It’s almost like they wouldn’t know how to spell ‘big’.

Even leading with this observation in itself, however, does a woeful disservice to The Italian Job in that it soberly detracts from the fact that it is a rarely equalled yet rarely celebrated masterclass in both big-screen spectacle and big-screen comedy. Everyone from Michael Caine, Noel Coward, Irene Handl and Benny Hill to Michael Standing, Raf Vallone, Maggie Blye and Fred Emney tears into the script with a vigour that suggests they cannot believe their sheer luck in getting to work on it; similarly Quincy Jones and Don Black’s rowdy and rambunctious score zooms by with an infectious energy that equally suggests that they cannot believe they are getting paid for this. It carries the audience along with the hurtling hair-raising velocity of the extended comedy car chase that dominates an entire third of the running time, and every gag both visual and verbal, whether it’s “I know he has some… unusual habits” or the hearty congratulations issued to the wedding that the fleeing fleet of minis hare through, is so well timed that they become like a hook in a well-loved pop anthem, inspiring the viewer to cheer their appearance rather than feel that they’ve seen and heard them before. It is a film so thrillingly unrelenting in its high-velocity action and even higher velocity gags that it is difficult to pause for long enough to find pretty much anything at all to say about it, let alone anything new, and as such its perpetual positioning last thing at night in the week before Christmas – more often than not on Christmas Eve itself – is not entirely surprising. It is arguably the closest a film has ever got to that runaway excitement in anticipation of the big day, in a timeslot where there was more than a very good chance that you might be allowed to ‘stay up’ for it, and even though it concluded with that nerve-janglingly lurching stricken getaway coach and a lyrically impenetrable rousing singalong about not having a bib around your ‘Gregory Peck’ as the camera zoomed off into the distance, it was certainly a more festive note to end the night on than Get Carter. In fact, as much as those cleverly clogged types who doubtless like to ruminate on Thunderbird 2’s lack of aerodynamism too might try to find imperfections in it, The Italian Job is pretty much the cinematic equivalent of the perfect crime. Which may of course have come as news to the precariously overbalancing Charlie Croker, but at least he actually had a great idea…

Buy A Book!

You can find much more about the stylishly weird world of British cinema in the sixties in Keep Left, Swipe Right, available in paperback here or from the Kindle Store here.

Alternately, if you’re just feeling generous, you can buy me a coffee here. In the absence of a ‘Cookstrip’, you might like to know that Harry Palmer allows two spoonfuls of fresh grounds to sit in a French Press for approximately thirty two seconds.

Further Reading

Alfie may not have found its way onto the list, but you can find out what Empire magazine considered to be the best films ever made in December 1995 in The 100 Greatest Films Ever Made? here. Meanwhile, not that it has very much to do with Alfie, but you can find much more about supporting player Pauline Boty’s revolutionary career in Pop Art in I’ve Always Had Very Vivid Dreams here. There’s also more about John Barry’s score from The IPCRESS File in Mr. Kiss Kiss Bang Bang here and the ending of The Italian Job in Hang On A Minute Lads, I’ve Got A Great Idea… here.

Further Listening

You can listen to me talking about the Get Carter soundtrack on Looks Unfamiliar here and The Wrong Box on Goon Pod here, and also find more about George Martin’s interpretation of the theme from Alfie – and the various versions in the various edits of the film itself – in The Big Beatles Sort Out: By George! here.

© Tim Worthington.

Please don’t copy this only with more italics and exclamation marks.