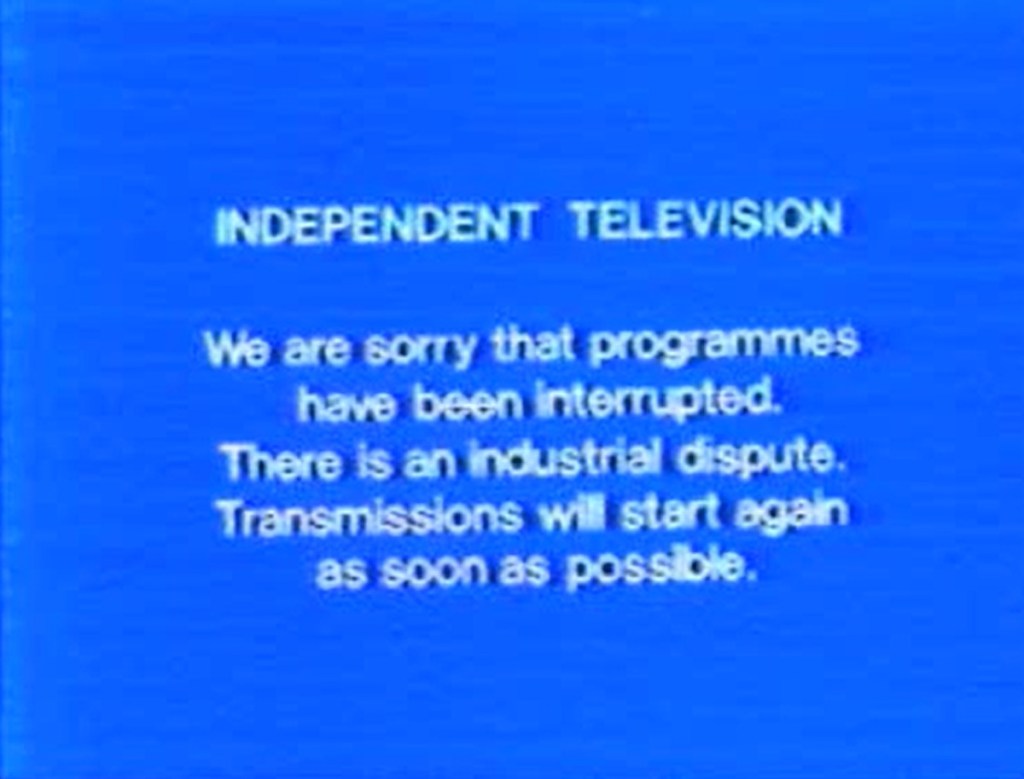

On 10th August 1979, what started as a reasonable demand by electricians at Thames Television to renegotiate an unsatisfactory proposed pay increase resulted in a mass walkout at fourteen of ITV’s fifteen regional broadcasters, effectively taking the entire network off the air for a whopping eleven weeks. For the best part of three months, viewers desperate to find out what Sapphire And Steel were up to at that haunted railway station were greeted with nothing more than a static white on blue IBA slide bluntly stating that “we are sorry that programmes have been interrupted – there is an industrial dispute – transmissions will start again as soon as possible”. While the unaffected Channel Television gamely ploughed ahead, doubtless resorting to deploying week-long instalments of Puffin’s Pla(i)ce, bereft ITV viewers reputedly to the tune of one million kept that slide on their screens in the vain hope that Bobby Ball might suddenly appear and exclaim “Normality resumed, Tommy!”. Those with something approaching a shred of sense, however, elected to switch over to the BBC.

Fortunately for the BBC, by accident rather than by any kind of design they happened to have an impressive line-up of potential hits ready and waiting for their unanticipated influx of new viewers. David Attenborough’s stunningly photographed history of evolution Life On Earth and Penelope Keith’s new sitcom vehicle To The Manor Born both found a massive and hugely receptive audience and record viewing figures that they might not have met with otherwise; the former’s lavishly illustrated tie-in book repeatedly sold out as the present-giving season approached, while viewers followed Audrey Fforbes-Hamilton’s downsized will-they-won’t-they antagonism with Grantleigh Manor’s new owner Richard DeVere as if it was a ratings-dominating soap opera storyline. The BBC had been trailing behind ITV’s glossier and more expensive Saturday afternoon imports for years, but suddenly The Dukes Of Hazzard and The Hardy Boys/Nancy Drew Mysteries were inspiring a million playground games involving pitch-perfect replications of the General Lee’s horn and Pamela Sue Martin’s running then stopping and looking round nervously then running again acting. A reasonable hit on its inaugural outing earlier in the year, full-tilt celebrity trash game show Blankety Blank became must-watch much-loved laugh riot appointment viewing virtually overnight.

Over in Studio 6 of Television Centre, with the first recording block for The Nightmare Of Eden about to commence, the Doctor Who production team must surely have been following events with keen interest, especially in the knowledge that they already had a long overdue return appearance by the Daleks and another story filmed almost entirely in Paris under their belt for the forthcoming ‘New Season’ on BBC1. None of them, however, can really have anticipated just how huge everything was about to get. A new Dalek story with discotastically fashionable new secondary antagonists and the return of Davros which was guaranteed huge press coverage on account of the headline-friendly supporting cast alone nudging close to fifteen million viewers was one matter. The fact that the story that followed was an uproariously witty and grippingly inventive Douglas Adams-written runaround set and filmed in Paris that dominated excitedly speculative conversations for an entire month, featured a cliffhanger that thrillingly terrified an entire generation and included a sidesplitting cameo from John Cleese – not only fresh from the success of the second series of Fawlty Towers but also dominating headlines thanks to his wittily barbed responses to the controversy over Life Of Brian – was something else entirely. City Of Death could almost have been made specifically for its unexpectedly doubled audience and it notched up an almighty seventeen million viewers, making it not only the most watched Doctor Who story but also, at least as far as sizeable proportion of fans are concerned, the best story ever full stop. That said, it also represented a high watermark that it would be to say the least difficult to meet moving forwards, and this tacit weight of expectation – especially when it relates to a story broadcast in the closing weeks of a decade and thereby almost instantly by default an object of nostalgia – is one of the most notable amongst several potential causes of Doctor Who‘s declining profile during the decade that followed.

Not everything else on offer from Doctor Who in 1979 alone, it has to be said, quite matched up to this standard, and while the first episode of the likeable but undistinguished The Creature From The Pit went out a couple of days after ITV resumed broadcasting on 24th October 1979 – an evening heralded by The Mike Sammes Singers triumphantly trilling ‘Welcome, Welcome, Welcome Home to I! T! V!’ but which soon descended into a lacklustre and threadbare lineup that included two interrupted mid-storyline soap operas and, with no small irony, the opening instalment of the downbeat and mutedly received Quatermass revival, which was noticeably short on “my dear, nobody could be as stupid as he seems”-level gags – it is almost certain that everyone concerned drew a small sigh of relief that certain adventures later in the run had not found themselves under so intense a spotlight. Overall, however – and much like the rest of the BBC – they must have been feeling like they could not believe their luck, little realising that industrial action would derail their own plans almost immediately…

Movellan Side Arms Killed The Radio Star

Destiny Of The Daleks, it is fair to say, does not enjoy the loftiest of retrospective reputations. Even on the rare occasions on which it is afforded a degree of grudging respect on account of its storyline, humour or visual flair, it is nonetheless held up as a textbook example – much like all of those other supposed ‘textbook examples’ – of a Terry Nation story where three men all called Tarrant are scowlingly attempting to stop something that The Doctor eventually realises they are actually starting or whatever it is, complete with a sort of Wes Parmalee Davros with Doug Yule on songwriting duties which forced anyone who had enjoyed classic Genesis Of The Daleks because it was a classic to have to join the New York City Newsboys Strike of 1899. All of which, it cannot be emphasised enough, does not exactly tally with the experience of younger viewers late in 1979, ITV strike or otherwise, who simply heard a shout go up from the front room of “QUICK – it’s half of a man and half of a Dalek” and hurtled in at a sideboard-colliding velocity to catch what they knew instantly was the best Doctor Who no arguments until a certain other half of a man incident later in that very same series. More to the point, such analyses invariably swerve any mention of the story’s brand new secondary antagonists drawn from the same gloriously absurd realm of inspiration as the Voord, the Exxilons, the Kraals and the Mire Beast – Legs & Co.-jumpsuited Floella Benjamin-coiffured Hot Gossip-accessoried androids The Movellans, who unusually appeared to enjoy, if that’s the right word, both tactical and technological superiority over the Daleks. About as Studio 54-ready a defining example of the Disco Sci-Fi phenomenon – which you can hear more about here, incidentally – as you are liable to find, the Movellans shared an unusually fashionable look that, as comical as it may appear from a present day perspective, you would have found all over Noel Edmonds’ Multicoloured Swap Shop, The Kenny Everett Video Show and Top Of The Pops at the time. Indeed, sitting at the top of the Top Forty throughout Destiny Of The Daleks was… well, it was We Don’t Talk Any More by Cliff Richard, even more inconveniently followed by the markedly more Blake’s 7-adjacent ‘synthetic human’ shenanigans of Gary Numan with Cars. Soaring up the charts towards the number one slot throughout September, however, was Buggles’ synthpop-defining New Wave masterwork Video Killed The Radio Star, assisted in no small part by a video that much like the song itself had ‘seen’ the future of home entertainment in the age of the silicon chip, complete with synthetic top pop groovy sounds artificially provided by what was to all intents and purposes a purplish Movellan in a sort of futuristic singing machine. How many viewers momentarily believed they had somehow stumbled across ‘extra’ Doctor Who when the video showed up on Roadshow Disco is sadly not on record.

“Something With A Bit Of Style And… Well, Style”

If any one series of Doctor Who exemplifies why Doctor Who fans struggle so much with the simultaneous instance of widely adopted truisms and cognitive dissonance that the series seems to attract, doubtless to the extent that that so many of them start babbling about neo-Gallifreyan Mutliverses and ‘woke’ and probably spinning around uncontrollably whilst doing so too, then it is without question series seventeen. It is, as we all know, characterised by silly childish slapstick humour that lowered the classic tone that we all remembered from classic stories where Jon Pertwee did one of his ‘funny’ ‘voices’ and The Anti-Matter Monster was permitted on screen without the entire production team being immediately arrested, and caused the entire audience to indignantly switch over en masse to Harold Lloyd’s World Of Comedy. At the exact same time, it is also the exact same series that we are relentlessly reminded is ‘decorated’ with comic ‘touches’ added by script editor Douglas Adams which if not quite fully up there with “…but that’s just peanuts to space” certainly dissuaded anyone from shunting themselves over to BBC2 in search of the more aesthetically edifying experience of laughing a while, digging that style and a pair of glasses and a smile. One of the most contentious manifestations of both diametrically opposed interpretations of Doctor Who humour – and for more reasons than its simultaneously slight yet witty comic content – is a certain notorious scene that takes place right at the outset of Destiny Of The Daleks. Whilst The Doctor is otherwise engaged with attempting to resolve K9’s apparent bout of ‘robot laryngitis’ – itself a gag that is not exactly as clever as it believes itself to be – Romana seemingly arbitrarily decides to regenerate. This, it should be noted, is, the conspicuously unacknowledged Borusa aside, the first occasion on which we have even so much as been made aware of another Gallifreyan regenerating – and no, The Master turning in to that decaying waterproof ‘walking jacket’ that someone has left on a coatstand at work and then denied all ownership of in a bid to quietly dispose of it doesn’t count – and it is fair to describe this not just as a wasted opportunity but a glib one at that. Initially casually assuming the form of Princess Astra of Atrios from The Armageddon Factor – and there’s more about the undue proliferation of Romana doubles here – Romana appears happy enough with her new look but is upbraided by The Doctor for essentially appropriating someone else’s appearance. Her two-fingered response is to parade around in a procession of patently unsuitable guises adopted with disconcerting ease – in order a sort of space age version of the woman in the hood out of Don’t Look Now if she’d been in a pocket with a giant leaking blue biro, the dancer from the cover of Juicy Lucy’s debut album and some kind of statuesque stilt-walking supermarket own brand version of the original Romana before she finally returns in an approximation of the Fourth Doctor’s signature outfit, hat-tippingly revealed to be Princess Astra once more. On the one hand, this is an amusing and original scene which Tom Baker plays with astonishing restraint, and perhaps more importantly still we got two totally distinct and equally brilliant Romanas out of it. On the other, it plays fast and loose with continuity for no good or evident reason even before most viewers would otherwise have understood continuity in practically any other context, and is also crowbarred in with all the subtlety of an animated Graham Norton declaring ‘Hi Pals – I’m up next!’. It is, rather appropriately in the counter-logistical manner of a certain entry from The Hitchhiker’s Guide To The Galaxy, both true and untrue at the same time and it’s no wonder The Doctor found himself a little exasperated and baffled, and indeed that acres of ensuing ‘fan fiction’ came a cropper on the next zebra crossing. Mind you, there was quite a lot of that sort of jarringly-inserted self-aware self-mockery around in 1979…

Do Not Disturb Until September 1st

In these days of carefully internationally co-ordinated ‘drops’ of teaser trailers essentially consisting of little more than a film or programme logo that changes two or three times before it comes out anyway, it really is odd to look back on a time when television promotion meant the programme’s presenters or cast – seemingly in or out of character on an entirely random basis – delivered largely improvised exhortations to watch directly to camera with a weirdly unsettlingly quiet ambience. Whether it was Paul Daniels essaying an infinite number of variations on his ‘…not a lot’ catchphrase even when he was supposed to be plugging Every Second Counts, Old Tel cheerfully promising ‘the very best in guests descending for a bit of an old natter in old Shepherd’s Bush… unless we can stop them!’ or any given combination of alternative comedians demanding ‘so tune in you barstards’ – ‘you barstard, stop calling them barstards!!’, the BBC’s scheduling attention-draw inserts in particular look especially dislocated and strange from this distance; accidentally surviving fragments that were even more ephemeral than the programmes that they were recorded on the set of, with a look and feel of something that fell off the edge of a BBC VT Christmas Tape’s Christmas Tape. Although many of the earlier examples no longer exist, Doctor Who was of course no exception to this, and one of the first to still be knocking about in videotaped form was broadcast a whole month ahead of Destiny Of The Daleks and, impressively, as good as constituted an entire mini-episode in its own right. Apparently caught off-guard during a stop-over in a sort of purple garden centre aisle, The Doctor – who is none too pleased at being bothered in the middle of August – is alerted by a mysterious voice to the fact that he will presently encounter the Daleks again, under the assertion that the forewarned is the forearmed, but is then informed that he will immediately forget about this crucial information, thereby essentially rendering him neither. Other than drawing in excitable viewers even before ITV sent them over by the coach trip load, which it doubtless more than delivered on, it is difficult to discern what the narrative purpose of this exercise was. More to the point, it appears to credit The Doctor with a degree of metatextual scheduling awareness of the sort that becomes tiresome in anything greater than one-line throwaway jokes in trailers and can never hope to be as genuinely cutting or even as funny as “When this programme returns, it will be put out on Monday mornings as a Test Card, and described by Radio Times as ‘a history of Irish agriculture”. Not that this stopped anyone, though.

“Merry Christmas, VT…”

Although it is pretty much a certainty that any attempt to explain the existence of BBC Christmas Tapes in a manner that any passing casual observer with little detailed interest in the matter above and beyond the level that you would understandably expect any sane and rational member of society to have will inevitably lead to vehement denunciation in an Archive TV Forum thread by a half dozen unaccountably exercised men tutting about you not understanding the internal politics that informed the assembly of the tapes and castigating you for not mentioning BBC Head Of Having Two Different Cutlery Sets In The Canteen Charles McHaltenwood whilst vigorously confirming that they saw Storyline: Mr. Egbert Nosh and wrote the name of it down in a Silvine exercise book and also pouring scorn on your sentence construction and punctuation despite the fact that their contributions will invariably be twice the length of this and somehow contrive to feature a negative amount of punctuation marks, but that’s precisely what we’re going to be doing here and yah boo sucks to frankmarker773. In short, the BBC’s VT engineers had a tradition possibly stretching as far back as the late fifties of covertly retaining any amusing mishaps or slip-ups from studio recording sessions and live broadcasts and editing them together for their festive bash into a sort of clandestine comedy clip show where you were more likely to see Miriam Margolyes telling an Assistant Floor Manager to fuck off than you were whichever Two Ronnie it was asking for andles for fourcs. Word soon began to spread about this illicit opportunity to chortle at your colleagues’ on-camera embarrassment, and pretty much every programme from Wildtrack to The Pallisers began to throw in their own cheeky winks to the ‘backroom boys’, with some big name stars even taking a trip down to the edit suite to record their own decidedly non-family friendly linking material. There is always someone who wants to spoil the fun, however, and the 1978 effort White Powder Christmas – which, in addition to The Goodies not being able to play a gramophone record on cue, a contestant on The Generation Game losing a battle with her neckline, The Three Degrees knocking over a microphone stand, Parky moaning at studio staff for not being ‘professional’, countless Blake’s 7 props collapsing, Fred Harris booting the uncooperative Play School toys across the studio and, regrettably, some bad dangers being bad dangers, also included a Princess Anne ‘shocker’ that wasn’t in the form of a horse-riding interview re-edited into mild innuendo – fell into the hands of the Sunday People with inevitable risible front page outrage ensuing. Legends are told of some very stern words being issued from ‘on high’, and even more intriguing legends are also told of the VT Department being hurriedly cleared of all manner of covertly retained tapes including unauthorised dubs of otherwise officially wiped programming from Not Only… But Also… to The Madhouse On Castle Street where nobody now knows where half of it ended up, but whatever actually went on there was nonetheless another Christmas Tape in 1979 and probably to the surprise of nobody whatsoever it heavily featured two of the BBC’s most popular shows of the year. The second series of Fawlty Towers had made its Waldorf Salad-ignorant sausages-excepting debut in February, and Good King Memorex is suitably awash with John Cleese and Prunella Scales reacting in character to unexpected studio slip-ups to a cacophonous wash of audience hysteria, especially when Cleese responds to a shaking set wall by immediately ‘tapping’ it with a ‘how much is this going to cost me?’ look on his face. Similarly Doctor Who – which the Sunday People had somehow failed to notice was also well represented in White Powder Christmas complete with Mary Tamm doing mock ‘horny on main’ and Tom Baker telling K9 that “you never know the fucking answer when it’s important, do you?” – crops up throughout, with noted witticisms including a Dalek saying ‘bollocks’ to Michael Aspel. As if all of that wasn’t enough, both shows also team up for maximum 1979 BBC-ness courtesy of the studio session for John Cleese’s cameo in City Of Death, which resulted in a series of improvised comic sketches between Tom Baker and what is essentially Basil Fawlty in all but name and arguably cut of suit, including one grimly hilarious exchange about an autograph that is not going to be recounted here, less out of fear of ‘cancellation’ than that a load of tedious sodding bores might start dribbling on about how you can’t make jokes about that now in private recordings that the public were never supposed to see because ‘woke’. Still, not all of Tom Baker’s coarse asides escaped the viewing public completely…

Do You Remember The Shrivenzale?

First seen in 1962, Animal Magic was a long-running and much-loved part-documentary part-comedy infotainment-skewed Children’s BBC series in which ‘Keeper’ Johnny Morris overdubbed animal character voices onto footage of natural history going about its natural historical business; in other words, lots of clips of skidding polar bears cheerfully exclaiming ‘look out below, fellars!’. Very little of which, it has to be said, ever found its way onto any Christmas Tapes. Like Crackerjack!, Screen Test, Take Hart and other hardly stalwarts of the informationally slash light entertainment slanted side of the Children’s BBC schedules, Animal Magic would continue through to 1984, when some contentious decisions were made to update tried and tested formats which nonetheless belonged to another televisual age with something more suited to the needs of contemporary audiences; you are of course free to draw a certain other parallel here. In fairness, the fact that Animal Magic bowed out with a dreary and interminable song about how Gemini the sealion’s name should be pronounced does lend some weight to this perceived need for a creative overhaul, but in equal fairness it had been struggling to adjust to a changing world of Native New Yorker by Odyssey and Alternative 3 for some time already. In the late seventies, Laurie Johnson’s long-established plonky showibizzy orchestral serenade of a theme tune had been given a tepid overhaul with showoffy wah-wah guitar and an electric piano seemingly stuck on a single note, and Johnny was joined by young trendy long-haired leather-jacketed co-presenter Terry Nutkins, who once daringly played Space Invaders in the studio. As if to underline this uncertainty of direction, numerous tenuous crossovers with other relatively younger viewer-friendly BBC productions began to feature as a matter of course, and on 1st May 1979 the audience were treated to what was effectively a preview of the in-production The Creature From The Pit as Tom Baker, clapped in wooden stocks, outlined the plot of the upcoming escapade before introducing clips of some of the strange and mysterious and conveniently recent creatures he had encountered on his travels and – although the insert tape was probably and indeed hopefully faded before this point – turning to the camera crew and denouncing the entire exercise with an extremely audible ‘oh god forgive me’. Not that any of the Children’s BBC viewers who were excited at getting an unannounced bit of brand new Doctor Who in the middle of all that business about the ‘seabird invasion’ will have really noticed even if they did leave it in, but the scarcely bonhomie-burdened at the best of times Tom Baker was already visibly and indeed audibly beyond his last shred of patience with a role he was nonetheless reluctant to relinquish, and certain parties really did notice that…

“Ah – The Planet Chromakey IV!”

Written by David Renwick and Andrew Marshall – who were very evidently not of the opinion that there was so much more than TV Times in TV Times Magazine – End Of Part One was an ITV sketch show that existed purely to ridicule television in its many and varied forms, all the way from blockbusting imported miniseries to regional in-vision continuity announcers, with a deft combination of scathing disdain and fun-poking absurdity. Originally intended for an older audience, it instead found itself in the children’s schedules – if anyone would like to argue about this, please do and I’ll send you the off-air recording with two minutes of The CB Bears before it – but the writers, firmly believing that younger viewers would be every bit as fed up with what they were being served up as small screen entertainment as their parents were, declined to pull any punches and the results were more savage than most ostensibly more ‘sophisticated’ attempts at ‘sending’ ‘up’ television. Younger family members pleaded to be allowed to ‘stay up’ to see the lobster on the roof at the start of Coronation Street, Brian Walden asked the politically volatile question “does anybody… ever… watchthis… programme“, The Man From Atlantis was bookended with ever more patronising safety warnings, Yasser Arafat showed up as the mystery celebrity guest on Larry Grayson’s Fat Ladies Embarrassment Game and Jon Pertwee liberally doused himself with teak oil whilst presenting Whodunnit?, whilst the Are You Being Stereotyped? theme ran on by an extra floor and an extra verse promising “everyone on one side of the table of the restaurant” before being abruptly cancelled; and, incidentally, there’s much more about End Of Part One and indeed many of the shows it lampooned in The Golden Age Of Children’s TV here if you’re interested. Inevitably – and especially considering the savage though not entirely unjustified baiting of Mr. Different Adams and Blake’s 7 that characterised Renwick and Marshall’s Radio 4 sketch show The Burkiss Way – Doctor Who could not evade their attention for long. In the final episode of series one, alongside the comedy stylings of The Two Quasimodos and an in-vision continuity announcer apologising for mispronouncing some silence, Doctor Eyes – introduced, incidentally, by the bizarre 1973 free jazz rendering of the Doctor Who theme by Don Harper’s Homo Electronicus – saw a boggle-eyed Fred Harris regenerate into Tony Aitken, accompanied by Sue Holderness as pink feather boa-twirling ‘Gloria’ and a sort of red Triang scooter twisted into the rough approximated shape of a robot dog, after being deposited by hand via model TARDIS on an all-too-convincing alien landscape fashioned from an all-too-unconvincing blend of cheap scenery and poorly rendered Colour Separation Overlay. As parodies of Doctor Who go, which is admittedly not a high set bar at this stage, Doctor Eyes is – as you would frankly expect from End Of Part One – withering, dismissive and driven by disdain for programme makers and viewers alike, but at the same time entirely fair and more importantly devastatingly accurate and, at least to any fan with a shred of humour and self-awareness, as close as you were liable to find to a shareable joke in a world of mop bucket-Daleked waffle about running up and down corridors. It was, however, based on an entirely fair and more importantly devastatingly accurate vision of Doctor Who that was around two years out of date, and certainly distinctly at odds with everything that secured such phenomenal viewing figures whilst ironically ITV was off the air, and in retrospect perhaps an early indication that even for the most popular and successful Doctor of them all, sometimes a change is as inevitable as it is necessary. It is possible that the fact that End Of Part One was directed by Geoffrey Sax, who later go on to play his own not inconsiderable part in dragging Doctor Who into the modern age, is not so much of a coincidence after all. That all said, 1979 also brought one measure above all others of just how popular Tom Baker was with his actual intended target audience…

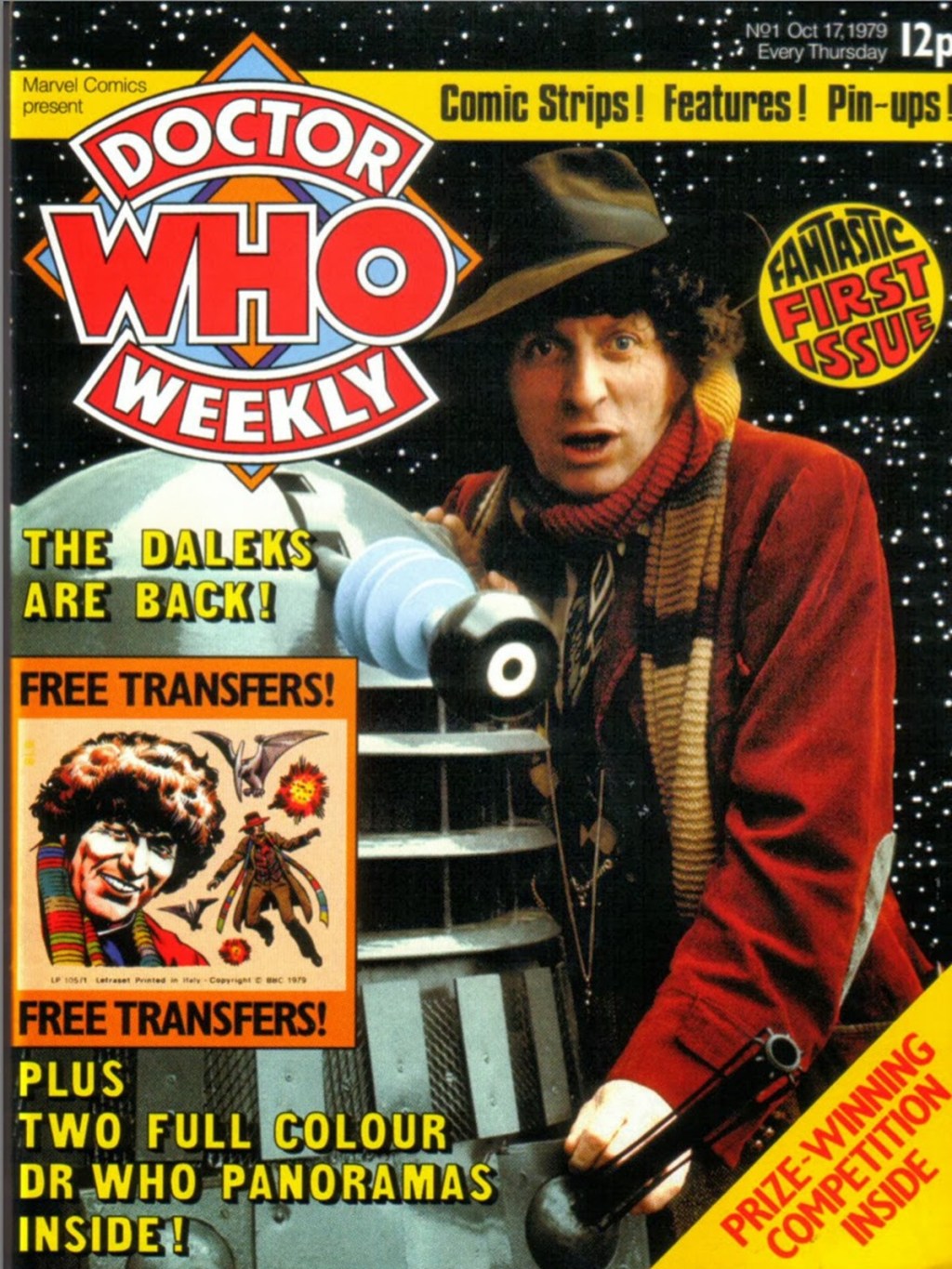

Fantastic First Issue

On October 11th 1979, with the enthusiastic promotional assistance of Tom Baker – including a memorable photo of him leafing through the magazine that frankly made Doctor Eyes look like an understatement – Marvel UK rolled out the very first issue of what was then known as Doctor Who Weekly. Boasting a combination of factual features, free transfers, archive photos and comic strips including the first part of the Doctor Who spinoff media-redefining epic The Iron Legion, it was carefully designed and curated to appeal to as many different divisions of the show’s audience as possible and it succeeded beyond anyone’s expectations; and if you want a measure of how exciting those readers found this brand new title, just ask Peter Ware – who himself would go on to contribute to Doctor Who Magazine in many different capacities – just how thrilled he was by the announcement that issue two would be going back to take a look at the very first ever Doctor Who story. ‘Old Vesuvius’ probably found it all rather exciting too, but we can probably guess what his reaction would have been, these days. In less than a year it would outgrow its origins dramatically and become the longer and more sophisticated Doctor Who Monthly and in turn Doctor Who Magazine, weathering the highs and lows of Doctor Who itself from the ‘Cancellation Crisis’ to the wilderness years, ushered in by the notorious ‘Waiting In The Wings – What Does The Doctor Do Next?’ cover feature and instantly finding its new footing with coverage of the many different non-television directions Doctor Who would soon take and the thrillingly informative and esoteric factual expeditions of Andrew Pixley, and leading the charge for the eventual triumphant return with Billie Piper memorably telling a press conference how excited she was to be working with such a vibrant and imaginative magazine. As much as the outside world might chortle ‘is that still going? co ho ho ho ho ho ho ho ho ho ho ho ho ho’ or even question whether it actually genuinely exists in the first place, yes it does and yes it is, and it’s still finding fresh angles in a changing world on what is quite possibly the most overdiscussed and overanalysed programme in television history. Well, there’s no The All-Electric Amusement Arcade Magazine, is there? More to the point, Marvel also tried their hand at a Blake’s 7 Monthly around the same time, which much like its band of fictional inspirations struggled valiantly but was always headed for a downbeat conclusion; Doctor Who Magazine, however, just went on and on even while Doctor Who itself didn’t and while it would be all too easy to divert into singing its praises for several million words here, suffice it to say that you would be hard pushed to find a stronger combination of adaptable subject area, relentlessly enthusiastic writers and editors, and discerning audience and that’s why you can still find it on the newsstands now with incoming new Doctor Billie Piper doing her own bit of Doctor Eyes on the cover. So that’s as much as we’re going to be saying about Doctor Who Magazine for the moment, although personally I would still like to know what was going on with that letter from Sam Skinner of Trottiscliffe who wondered if his BBC Videos had scenes that did not appear on the tape. Mind you, the fact that the magazine was launched during the transmission of a certain story should probably not go unremarked upon…

Is City Of Death The Best Doctor Who Story Ever?

Licence Denied was the now frankly barely comprehensible title of a 1997 Virgin Books anthology edited by Paul Cornell, which collected an immensely readable assortment of highlights from the black and white photocopied fanzines – or ‘rumblings from the Doctor Who underground’ – that had flourished in the wake of Doctor Who‘s cancellation in 1989. Ambitious, acerbic and absurdist to a degree that arguably may not have been possible or even necessary if the series had carried on and amateur writers and artists had neither a defined history to evaluate or an absence of new episodes to react against, they represent a creative and critical approach that was scarcely in evidence barely eighteen months previously. Even if he did only elect to use a single paragraph from a certain title very consciously modelled on the fanzines that indie bands’ ‘people’ used to mill around venues flogging to punters who had come to see the support acts. Ahem. One of the features that did find its way into Licence Denied, however, was The Lovers by Ian Berriman, originally published in issue one of Purple Haze over the summer of 1990. The Lovers is a wild, impressionistic, kaleidoscopic stream of consciousness explaining why and how Ian loves Tom Baker and Lalla Ward both as much for their on-screen chemistry as for the tempestuous off-screen romance that dared a smitten young fan to dream, punctuated both with quotations from turn-of-the-decade indie pop lyrics and vivid recollections of counting down the seconds until Doctor Who on a Saturday afternoon a whole turn of the decade earlier. Simultaneously self-aggrandising and self-mocking, strewn with highbrow allusions and lowbrow pop culture references and affording the same degree of analytical vigour and verbosity as a broadsheet magazine columnist might have reserved for a Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen exhibition to that programme that had the Occuloid Tracker in it, The Lovers is everything that a feature on Doctor Who written entirely for your own enjoyment should be. Perhaps unsurprisingly, one story is referenced in The Lovers more than any other or indeed all of the others put together – City Of Death.

It is probably a measure of how highly City Of Death is regarded that it has been almost casually afforded that rarest of accolades in this lengthy series of equally lengthy features – a second paragraph. As good as written over a weekend by Douglas Adams when David Fisher’s original script for A Gamble With Time failed to prove workable, City Of Death has an ingenious premise rendered with flashes of both comic genius and terrifying implications for the universe, lavish location work in Paris that for once adds genuine flavour and atmosphere to a story, stunning model work that makes a nonsense of all of that snorting garbage about rubber walls and cardboard monsters, a genuinely hilarious cameo from John Cleese and Eleanor Bron as a pair of pretentious art critics, an unwanted sidekick who values a good honest walloping above subterfuge and strategy, snappy dialogue punctuating elaborate double-crossing and mind-melting time-straddling solutions to temporary setbacks, and a cliffhanger where Count Scarlioni reveals his true face-tearing form which even erstwhile viewers who have no idea of what he or the story was called still recount with a shudder and which was so deftly filmed and edited around its limited resources that it has lost none of its impact even now. Over and above all of this, however, it has, well, ‘The Lovers’ not just at the height of their abilities and rapport but possibly the most vivid manifestation of the relationship between The Doctor and a fellow TARDIS traveller of all. There is an extent of course to which it was the right story at the right time, but even so, that is arguably part of the point in and of itself – City Of Death is so good that it was able to take the fullest possible advantage of an unexpected opportunity without even trying; as a contrast it is difficult to imagine, say, The Time Monster holding its own against a static blue caption slide. In all honesty Doctor Who has taken so many different forms at so many different times that the idea of a ‘best’ story ‘ever’ is as redundant as it is subjective – after all, we’ve already taken a look at another story that is routinely afforded the exact same accolade here – but the fact that nobody ever challenges this assertion with regard to City Of Death speaks volumes. Mind you, there is Time And The Rani. The more inconvenient question, however, is why none of the stories that followed it ever seem to be found anywhere other than lurking around the lower reaches of ‘best’-based rankings of Doctor Who stories…

What Went Wrong With The Rest Of It?

Conceding a whopping and deserved forty five percent pay increase to the striking workers and quietly ruminating on their reputed loss of one hundred million smackers in advertising revenue, ITV returned to the airwaves with a somewhat muted display of fanfared bravado on the evening of 24th October 1979. Aware that Saturday evening was just one of many scheduling corners where they needed to regain some of the ground comprehensively lost both to the BBC and to just going out and getting some fresh air, they literally scrambled for juvenile attention with the tried and tested ringing-synthed discotastic mild crimebusting exploits of ‘Jon’ and ‘Ponch’ of the California Highway Patrol in CHiPs, with a higher profile import that would pose a far greater challenge biddi-biddi-ing away on the not too distant horizon. Meanwhile, Doctor Who ploughed ahead with the first instalment of The Creature From The Pit, a story essentially about a green plastic bag held to interplanetary ransom in an unsubtle commentary on intercontinental trade agreements, which admittedly lacked the highs of Destiny Of The Daleks and City Of Death but was nonetheless a fun runaround vividly realised and with a hefty dose of wit that almost verged on self-aware jokes about its shortcomings, doubtless encouraged to put it mildly by Douglas Adams. After that, however – and doubtless to the relief of Erik Estrada – everything just seemed to fall apart. Ostensibly a harder edged story about narcotics smuggling and racial exploitation, The Nightmare Of Eden ran in to trouble during production that it never quite recovered from, after director Alan Bromly stood up to a tantrum-throwing Tom Baker and walked off set refusing to return; although that said, the fact that the plot revolved around a process that was difficult to realise with the available resources and studio time and involved poorly designed aliens and then had to be more or less entirely edited out when the episodes overran anyway did not exactly help. Frustratingly for anyone who actually braves The Nightmare Of Eden, all of the elements of a good story are in there somewhere; they just aren’t anywhere near each other at any given point. The Horns Of Nimon, on the other hand, resolutely refuses to care that more or less everything about it is little short of panto and certain of the cast are not exactly backwards in coming forwards in their acknowledgement of the inherent oh-no-it-isn’t-ness either, and while it is certainly a story that fans can have a good deal of fun with, its impact on New Season-hungry autumn audiences must have left more than a little to be desired. Coming out of a moment where it had become a genuine national talking point, Doctor Who spent eight weeks vacillating between silliness and dullness across two stories so unloved and unremarkable that a certain writer might well have made a note to discuss the ‘Cheggers Plays Pop effect’ in one of them but can neither remember which one it was nor whether this referred to a visual or sound effect, and even then whether the latter would have been the hooting end of round four note klaxon or the other end of round nose-thumbing guitar riff. As much as Doctor Who may have found itself in the ascendant through a quirk of timing, it was suddenly back to business as usual through an equal and associated quirk of timing, and as much as there may be to enjoy in both The Nightmare Of Eden and The Horns Of Nimon, it is exceptionally likely that they were at the forefront of the thoughts of a certain ambitious member of the production team who had found themselves increasingly exasperated by the rest of the BBC’s attitude that ‘it’ll do because it’s Doctor Who‘. What was more, it would get worse before it got better…

SHaDA

The Horns Of Nimon, of course, was not actually supposed to see out series seventeen and indeed the entire seventies for Doctor Who. Instead, had everything gone to plan, the misfires of the past couple of stories would have been quietly forgotten thanks to a six-part Douglas Adams story set in Cambridge and with an offbeat romance-infused storyline, an approach to science and an overall degree of degree-level wit that sat much closer to what he had recently been up to on the radio with Wowbagger The Infinitely Prolonged and company than it did poor old Erato. Location filming for Shada – itself mildly disrupted by industrial disputes – had wrapped in mid-October, and everyone involved was by all accounts as enthused as they had been by City Of Death. The first studio recording block in early November proceeded with as few hitches as Doctor Who in 1979 was likely to experience; the two scheduled further sessions, however, were scuppered by ongoing industrial action that may or may not have involved a disagreement over who operated which bit of the Play School Clock. Nobody is quite sure, although it is tempting to consider that some of the blame can be apportioned to Humpty in a Clock Operator’s hat that says Clock Operator on it. By the time that the dispute was sufficiently resolved to at least allow everyone back in the studio again, it was practically advent and all available recording blocks were needed for Christmas With Telford’s Change and Fred Dibnah showing up on chat shows ‘as’ ‘Santa’, and Shada simply had to languish unshown and unfinished. Incoming producer John Nathan-Turner argued to be allowed studio time to remount production but this was not forthcoming, and Douglas Adams – who by that point had become an overnight literary megastar – started to become concerned that the scripts were not up to standard and began to grow resistant to the idea of Shada being completed, to the extent to refusing to grant permission for it to be novelised by Target books. After that the story quietly sank into obscurity and it is possible that many fans did not even really know of its existence until Doctor Who Monthly ran a feature on it in October 1983, complete with one of the least enticing covers it has ever had. This timing was not entirely coincidental, as thanks to Tom Baker’s refusal to participate in The Five Doctors, John Nathan-Turner sought to at least partially redress viewer disappointment by covering for his absence with previously unseen footage from the Shada location shoot. Around this time, some of the location and studio footage began to leak out, and one enterprising fan collated this into a rough assembly of the completed scenes in something approximating the correct order, with indeterminately originated home computer text explaining the missing bits of action and in some cases the missing effects from the location sequences, and also a bit where the picture went all wonky and started squiggling back and forth before cutting to a subliminally brief clip of Mackintosh Mouse from The Sunday Gang and then abruptly back to the prison ship scene, explained away by more knowledgeable fans as a ‘marker’ inserted so that well-connected video-procuring types could keep a close eye on how many duplications of their hard-negotiated wares were getting out though in all honesty it’s more likely that someone just pressed record by accident. BBC Video issued a somewhat slicker version in 1992 – which Douglas Adams claimed he had sanctioned by mistake – which covered the gaps with new effects, a pastiche score from Keff McCulloch, and linking narration from Tom Baker wandering around the MOMI Doctor Who exhibition saying ‘aahhhhhh – how’s the garden shed, geezer?’ to Magrik, packaged with a miniature script book and an official Doctor Who piece of polystyrene. For his part Douglas Adams twiddled around a few names in the supposedly substandard scripts and reworked them into Dirk Gently’s Holistic Detective Agency in 1987, whilst laudably taking personal responsibility for his persistent decision not to allow Target anywhere near Shada; many years later, Gareth Roberts would pen a finally officially sanctioned novel based on Shada that gave a creditable idea of what Adams might have done with it whilst still retaining its own character, and tied the story in with wider Doctor Who lore as well as Monty Python, Hitchhikers and, amusingly, Dirk Gently. Big Finish produced a full cast remount starring Paul McGann as a Flash animation-accompanied audio drama in 2003, brilliantly adapted by Gary Russell and even incorporating an in-story explanation for the footage appearing in The Five Doctors, which despite being by far the most visually consistent and in many respects the most interesting attempt at recreating Shada has now apparently been officially downgraded to an ‘other adaptation’ in deference to the more divisive BBC-initiated animated gap-pluggage in 2017 and 2021, which didn’t even include Mackintosh. There was also, of course, Shardovan’s Shada Van, a charitable initiative in which the big-hatted Castrovalvan nemesis also proved to be big-hearted by voluntarily driving across the country with a van full of props from the abandoned story to give underprivileged children who couldn’t afford the £19.99 BBC Video release the opportunity to see what the Krargs and the big hat that evil bloke wore looked like, which surprisingly did not find its way into Licence Denied. All of which means, without wishing in any sense to denigrate the it has to be stressed welcome and accomplished efforts of anyone involved at any point, we now have a pick’n’mix of approaching a dozen entirely independent approximations of Shada to choose from where we once had one hundred and sixteen seconds and before that nothing at all – and that’s… well, it’s a good thing actually. There’s no arguing about that. It’s not just more Doctor Who, it’s more Doctor Who that ably demonstrates just how creative, inventive and tenacious its fans are. That all said, much like The Beach Boys’ legendarily abandoned album SMiLE – which there’s much more about here if you have little to no idea of what Mrs. O’Leary’s Cow may or may not have to do with anything – we are awash with attempts at finishing an abandoned project that is evidently unfinishable to anyone’s definitive satisfaction, and in the process some of the excitement of having a tantalisingly lost element of Doctor Who history, so near and yet so far from completion with thrilling question marks hanging over the puzzle of how it would have all fitted together and why, has itself been lost. Most Doctor Who stories, of course, have the one version and that’s it. Yes, it is way better that we have all of these different iterations than we don’t, and Professor Chronotis would doubtless have been amused by the paradox of this being argued by someone who also persistently argues for the availability of The Beatles’ similarly infamously shelved electronic track Carnival Of Light, or at least he would for about three seconds before wandering off muttering about where did he put those pikelets or whatever it is, but at the same time we should try to keep sight of the value of an excitingly unanswered question in a world that increasingly devalues them for the sake of content saturation. There’s also probably a wider point to be made here about the general overabundance of ‘extras’ and alternate versions that nobody asked for across all media, but we’re probably best avoiding that for the moment. Now where did I put those three different edits of The Daleks – 21 Minutes Of Adventure…

Anyway join us again next time for Doctor Who still ‘borrowing’ from The Quatermass Experiment, Chris Rea’s ‘beef’ with K9 and the unacknowledged importance of Mr. Benn and Fred Bubble to JNT’s relaunch…

Buy A Book!

There’s lots more about Animal Magic and End Of Part One along with numerous other children’s television shows that benefitted – to varying degrees – from Tom Baker’s participation in The Golden Age Of Children’s TV, available in all good bookshops and from Waterstones here, Amazon here and directly from Black And White Publishing here.

Alternately, if you’re just feeling generous, you can buy me a coffee here. In a BBCVT Tea Styrofoam cup, please. But definitely coffee.

Further Reading

You can find more about the logistical headache underpinning the unfeasibly various iterations of Romana in It’s Still A Police Box, Why Hasn’t It Changed? Part Seventeen: Uptown Top Ranquin here.

Further Listening

There may be – unfortunately for Shada obsessives – only the one version of it, but you can find a look at some long-forgotten Doctor Who-associated spin-off side project oddities in Doctor Who And The Looks Unfamiliar here.

© Tim Worthington.

Please don’t copy this only with more italics and exclamation marks.