In the autumn of 1978, Doctor Who was sent off on a very long quest indeed. At the behest of the White Guardian of Time, The Doctor and his new travelling companion Romanadvoratrelundar – a fellow Gallifreyan whose ferocious intelligence, strategic rationale and sharp dress sense provided young female viewers with a much-needed role model in substantially the same yet also somehow exact opposite manner as Leela’s corresponding lack thereof had done (although you can find some more nuanced and indeed enthusiastic thoughts about her influence on the audience here) – were tasked with finding and assembling the six translucent puzzle pieces that collectively formed The Key To Time, a cosmic cube presumably not in any way related to Marvel’s contemporaneously recurring Cosmic Cube that ostensibly maintained universal harmony and balance but which if it fell into the hands of the Black Guardian would, in short, not. It is more than likely that nobody involved in telling this lengthy overarching story-straddling story saw it as anything more than a fun and inventive way of approaching Doctor Who that gave viewers something a little different, but in a sense it was effectively a rudimentary forerunner of everything that tedious thinkpieces in The Guardian will insist on telling you was invented with the rise of ‘authored television’ and specifically by Buffy The Vampire Slayer, The Sopranos, Game Of Thrones or wherever they have moved the goalposts to this week. It is also worth noting that only a couple of years earlier, Richard Carpenter had been talked out of including scenes showing the historically displaced sorcerer surveying his accumulated haul of the thirteen – yes, thirteen – signs of the zodiac in the second series of Catweazle, out of a concern that American networks might arbitrarily show the episodes out of order. Most significantly, however, it had been on beleaguered and unpopular producer Graham Williams’ ‘to-do’ list pretty much since day one.

Ironically at least partly on account of the poisoned chalice shunned by Sarah Jane in The Brain Of Morbius, it is fair to say that Graham Williams had been handed something of a poisoned chalice when he took over as producer of Doctor Who. Still hampered by the time-honoured lack of resources and restrictions on studio time and studio practices, he had been handed the unenviable and frankly staggering task of somehow retaining Doctor Who‘s currently level of popularity whilst entirely eradicating more or less every creative aspect that had made it such a success in recent years. Ongoing tensions between Williams and the increasingly difficult Tom Baker would boil over during production of their second run on the series, with a blunt refusal of Baker’s demands to be given approval over scripts, directors and casting causing him to threaten to quit if his conditions were not met, which in turn provoked Williams into attempting to have his lead actor dismissed. Outside of the actual production difficulties, while Mary Whitehouse herself may have turned her attentions elsewhere – most infamously with vigorous campaigning against the proposed general release of Monty Python’s Life Of Brian but also, it has to be stressed, with sustained attempts at codifying measures to silence Gay Rights organisations into enforceable law – many of her bandwagon-jumping acolytes were still routinely denouncing the by now significantly more restrained Doctor Who as a ‘teatime’ horror fest that should be ‘banned’. Making matters more complicated whether they realised it or not, the emergent and increasingly influential organised Doctor Who fandom, despite largely having not tremendously greatly cared for some of the narrative excesses of recent series, now were very much of the opinion that the latest offerings marked a considerable downturn in quality. Then, apparently least of all, there was the general viewing public who frankly could not have cared less and tuned in regardless whilst having undue hysterics at the merest mention of a ‘megagalactic scarf’ or something.

Even over and above all of that, the actual medium of television itself appeared to be attempting to halt the bold and ambitious narrative in its tracks. Tom Baker turning up to a studio session with a hugely swollen lip after a philosophical debate with a dog went ‘south’ was easily compensated for with a dash of makeup, and orders from on high to abandon a scene in which The Doctor was surprised with a birthday cake to celebrate the show’s fifteenth anniversary was resolved by everyone eating the cake, but increasingly bizarre and unanticipated broadcast interruptions were another matter altogether. The first episode of The Power Of Kroll only narrowly averted – literally by a matter of hours – being forced off air by a BBC strike that put paid to a good proportion of the intended festive jollity including the Rentaghost Christmas Special (and there’s more about that seasonal oddity here), but the transmitters were not done done with Doctor Who yet and the crucial sixth and final episode of The Armageddon Factor and indeed the entire Key To Time storyline fell off air for a full minute, resulting in frantic deployment of the Starsky And Hutch theme and a Temporary Fault caption.

Considering the sheer volume and indeed cumulative effect of all of the above, it may well present the impression that the Black Guardian really ought to have put his feet up as nobody wanted the ‘Key To Time’ series to be made in the first place. Yet what all retrospective assessments tend to overlook, even over and above the fact that they found inventive ways of introducing each ‘key’ to prevent the individual storylines from becoming repetitive or that it introduced not just one of the greatest Doctor Who writers but even one of the greatest writers full stop, is that it all seemed entirely acceptable and enjoyable to the actual audience that it was aimed at. There is a reason why there is still fervent speculation on when and in what form series sixteen will appear on whatever the latest new home entertainment format is, and that is because it was a collection of mostly diverting and exciting individual stories with an interlinking theme that gave those hardy viewers bravely averting their eyes from the BBC’s terrifying Santa Head ‘Globe’ to keep up with The Doctor and Romana’s progress exactly what they were looking for. That ‘mostly’ is important to keep in mind, though…

Why Does Nobody Love The Ribos Operation?

Had the Key To Time not required reassembly for what it is never entirely clear whether it constitutes good reason or not, then this particular run of Doctor Who would have commenced with an adventure – presumably – involving The Doctor and K9 taking a holiday on Halergan III, a planet apparently characterised by beaches, palm trees and day-long sunshine. Instead, after a blast of cathedral organ and an encounter with an impeccably safari-suited White Guardian lounging in a wicker chair in a sort of orange void, looking for all the world as if he is about to simultaneously issue an affirmation on behalf of the Del Monte Foods Inc. and volley forth some ‘Odd Odes’, and the accompanying thigh-panning introduction to Romana, it’s straight off to a planet characterised by climatic conditions that they might have expected from a holiday somewhere in Britain, only possibly even moderately milder than that. An everyday story of smugglers, scramblers, burglars, gamblers, pickpockets, pedlers and even panhandlers on a chilly planet bearing more than a passing extravagantly-hatted resemblance to Sixteenth Century Europe, The Ribos Operation is a thoroughly entertaining runaround of swindles, twists and economo-political chicanery; it is also one that you are not particularly liable to find anyone mentioning very much. There is no real reason for this other than it is essentially just there – The Ribos Operation is nobody’s favourite story, and neither is it anyone’s least favourite, they just know that it comes at the commencement of the Key To Time storyline and has some business in it about ‘scringe stone’ and Binro The Heretic exercising suspicion about ice. It is a strong story and well acted and vividly realised, but there is little that really stands out about the machinations of the Graff Vynda K and company and as such it falls into that unfortunate bracket of Doctor Who stories that everyone just sort of forgets about. In a celebrated scene from The Wire – which it has to be said is not a million miles removed from The Ribos Operation in terms of its general narrative themes and fixations – ambitious drug baron Russell ‘Stringer’ Bell tries to impress the importance of properly completing assignments on his hard of thinking operatives Gerard and Sapper through the example of a ‘forty degree day’, which, being neither particularly hot nor cold, generally passes without comment. Admittedly the entire structure of audience response now appears to require anything and everything to be as warm as Halergan III or as chilly as Ribos with no consideration for any gradations in between, but is there honestly anything wrong with a Doctor Who story that has the temerity to just be good, especially if it’s as good as The Ribos Operation? It really is time that the Jethrik-rustling interlude on the elliptically-orbiting planet was afforded a little more attention. After all, it doesn’t have any distractingly inadvertent echoes of popular advertising figureheads scattered throughout it…

“HO HO HO… Rohm-Dutt!”

On discovering the existence and availability of the oversized and palatability-challengingly flavoured Prince Of Wales Pea in 1925, The Minnesota Valley Canning Company elected to market them to an easily fodder crop-duped public as the ‘Green Giant’ variety, enlisting the services of a sort of angry caveman even by caveman standards to help establish their consumer appeal. By the early fifties, he had evolved into a jovial booming-voiced sort of foliate Incredible Hulk who presided over the allegedly comedic exploits of farmers and factory workers in his ‘valley’ in a series of much-loved animated commercials. Originally introduced by a sort of trilling vintage radio ident close harmony jingle punctuated by his chortled ‘HO HO HO’ – which inspired Louie Louie hitmakers The Kingsmen to expand it into a song questioning whether he, erm, ‘gets’ ‘any’ – by the mid-seventies he had acquired a corn-themed juvenile sidekick to pose questions related to freshness and associated shopper concerns and a catchy loungey light pop signature song, which enjoyed particular popularity in the UK courtesy of saturation showings in ITV’s commercial breaks. All of which simultaneously both explains and makes it all the more audacious why whoever was responsible for designing a race of ‘dryfoot’-resenting quasi-amphibious natives of Delta Magna for The Power Of Kroll opted to essentially ‘borrow’ the animated asparagus-profferer’s look in the apparent belief that the audience of viewing juvenile millions would not immediately bellow what passed for his catchphrase on catching sight of Varlik and company. In a story already substantially undermined by over-emphatic drum paradiddles and the assorted canned goods-adjacent minions shouting ‘KROLL! KROLL! KROLL! KROLL!’ as if their oversized cephalopodian overlord was engaged in a playground skirmish with the school bully, let us just say that this did not help. Although as it turned out, the search for the Key To Time would prove to be something of a not exactly rogue’s gallery of inadvisedly gimmicky adversaries…

If Your Mr. Fibuli Needs Intimidating Just Call… Polyphase Avatron!

From the grouchy non-slip shower mat that has reacted with the wrong kind of bathroom cleaner masquerading very very minimally as The Shrivenzale in The Ribos Operation, to the blindfolded raid on the dressing-up box that constituted the Taran Wood Beast in The Androids Of Tara, it’s fair to say that The Doctor and Romana’s quest to locate the various segments of the Key To Time was beset by more than its fair share of memorably unmemorable monsters. Few, however, have ever proved to be quite so memorably unmemorable as Polyphase Avatron, the mechanical psittacine who perched on the shoulder of The Pirate Captain like some kind of Pieces Of Eight Volt Battery-cawing space-age Captain Flint before being dispatched to wreak eye-zapping havoc in The Pirate Planet. One of Douglas Adams’ less epochal plastic pals who are fun to be with, and easily outmanoeuvred by a frankly disdainful K9, it nonetheless scored highly with Doctor Who‘s audience not just on account of the inherent novelty value but also by virtue of pushing Bruce Purchase’s already worryingly convincing performance to an extreme where you could almost believe that he believed his shoulder-mounted subordinate to be ‘real’. As a one-story sidekick, Polyphase Avatron fulfilled its role admirably, but it was to prove to have an unexpected legacy that few have acknowledged; not long afterwards, the Children’s BBC sitcom Rentaghost – which really does seem to be crossing paths with Doctor Who a good deal around this time – introduced its own more benevolently chaos-causing robotic parrot ‘Polly Styrene’, with the only real substantial difference between the two being that it was kitted out in its inventor Mr. Claypole’s established merrymaking colour scheme. Although it is unlikely that Polly was a direct refurbishment of the actual Polyphase prop, which of course would stand teetering on the Captain’s shoulder at the Blackpool Doctor Who Exhibition for many years thereafter, the two avian iterations are nonetheless sufficiently close in design and indeed execution to invite conclusions suggesting something more than coincidence. Meanwhile, speaking of apparent Children’s BBC-related coincidences…

“Ah – Ludwig!”

On Monday 20th June 1977, what appeared to be the strongest indication yet of evidence for the existence of intelligent extra-terrestrial life was found in woodland in the South West of England. Surprisingly this did not make the BBC’s main Evening News, although that was possibly down to the fact that it actually appeared just before it. Created by Mirek and Peter Lang and narrated by Jon Glover, Ludwig depicted the Beethoven-driven minimalist escapades of a sort of robotically-limbed crystalline stranded alien entity and some inquisitive rodents and stroppy birds as they got up to all manner of bicycle horn beak-prodding merriment as observed by a permanently binoculared birdwatcher who appeared to see no issue with any of the events he was witnessing. Repeated dozens of times into the early eighties, it was almost certainly an entire coincidence that Ludwig whizzed back in to the schedules on his ‘helicopter blades’ arm while the hunt for the six segments of The Key To Time was in progress, but even so, it has to be said that the sheer amount of instances of The Doctor wandering around grassland and forests – or what least passed for them in terms of cheaply available filming locations – attempting to wilfully indulge in naturalist-friendly pursuits, whilst noticeably dressed not unlike a certain cartoon birdwatcher and stumbling across some conspicuously odd happenings unfolding in the middle distance and usually remaking upon this with a standard Tom Baker ‘Ah!’ to boot, is at least moderately vaguely suspicious. It’s certainly a sobering thought that had this run of Doctor Who been delayed by even a few weeks – after all, the actual concept of television itself appeared to be actively conspiring to prevent it from being shown or even made in the first place – there may well have been multiple instances of The Doctor donning a sou’wester and exclaiming “All aboard the SkyLar… I mean TARDIS!” instead. As it transpired, however, Tom Baker was already acting more than a little Doctorishly in some corners of the schedules where most viewers feared to tread – and not without good reason…

The First Of Five Horror Stories Read By Tom Baker

On 3rd January 1979 – midway between episodes two and three of The Power Of Kroll – ITV broadcast the first ever instalment of The Book Tower. Created by Yorkshire Television for the Children’s ITV slot, it sought to encourage the sort of youngsters who might not normally pick up a book to give one a try by involving them in imaginative readings from, dramatised extracts of and ‘book club’-style interactive postal discussions based on books that they might actually voluntarily want to read rather than be told that they were expected to read. Nominally set in the suitably mysterious library of Sudbury Hall and equipped with equally dramatic theme music from the then still just-about hip and trendy Andrew Lloyd Webber, The Book Tower would run through to 1989 with a procession of hardback-toting hosts, the first of whom – who would stay with the series until 1981 – was none other than Tom Baker, essentially essaying his literary duties as ‘The Doctor’ in all but name. You can of course find much more about The Book Tower in The Golden Age Of Children’s TV here, but what rarely ever seems to get acknowledged is that immediately before leafing through The Boy With The Bronze Axe by Kathleen Fidler, Tom Baker was involved in yet another distinctly Doctor-ish story-reading engagement; and given how many erstwhile younger viewers appear to have found The Book Tower itself decidedly ominous and gothic, we can only hope that none of them pleaded to be allowed to ‘stay up’ for it. One of BBC2’s infrequent but repeated and determined attempts to establish a late-night storytelling slot for adults, the appropriately named Late Night Story ran as a very nearly week-long tryout between 24th and 29th December 1978, with Tom Baker reading adaptations of The Photograph by Nigel Kneale, The Emissary by Ray Bradbury, Nursery Tea by Mary Danby and The End Of The Party by Graham Greene; a fifth instalment featuring Sredni Vashtar by Saki would have opened the series on 22nd December but it fell victim to the very same industrial action that very nearly delayed The Doctor and Romana in their segment-seeking activities. Given the intentional macabre tone of the selections the series was relegated to 23.55pm – the very last thing seen on BBC2 that night, doubtless followed by the continuity announcer making an uneasy attempt at a jocular sign-off and equally doubtlessly by viewers hurriedly switching over to BBC1 for the suddenly exceptionally reassuring tones of the weather forecast – although it is tempting to speculate that this scheduling decision was not so much informed by the stories themselves as how they were rendered. The opening titles of Late Night Story featured a wonky music box motif that clearly believed that the fadeout of Asleep by The Smiths was spoiling it for the other music boxes by being too jolly, accompanying creepy scratchy drawings of a child with her eyes and mouth sewn shut and a teddy bear with her errant facial features crudely stitched onto it. Even more terrifying than that, however, was Tom Baker himself taking a seat in a well-appointed but airless drawing room and reading out the nightmarish plot twists with boggle-eyed minutes-long stare-into-camera relish. Even considering his pre-Doctor Who background in low budget UK horror movies and intra-Doctor Who actorly tendency to gravitate towards the more literate corners of television such as Read All About It and Call My Bluff, Late Night Story really does seem a jarring anomaly and one that any reasonably well balanced individual would caution against watching in its original intended timeslot even now. What is more, it was also in many ways harking back towards a gothic horror-inclined tendency that Doctor Who itself was by then under rigorous instruction to distance itself from. Ultimately, this really does all go to show that even when it comes to the lure of ‘extra’ Doctor Who by proxy, you do have to draw the line somewhere and that while The Book Tower is right up there with What’s Your Story? and Whodunnit? and even some others that did not involve question marks, Late Night Story is perhaps best filed alongside The Little Green Man and Crosswits, more for the sake of your own sanity than anything. Anyway, let us move on and concern ourselves with something notably less disconcerting.

Why Isn’t The Stones Of Blood ‘Hauntology’?

In January 1977, ITV broadcast the first episode of Children Of The Stones, a celebrated HTV children’s serial written by Jeremy Burnham and Trevor Ray about a family moving to a mysterious rural community with a sinister secret revolving around a megalithic stone circle. The writers would follow Children Of The Stones later that year with Raven, a similar children’s serial for ATV starring Phil Daniels as a teenage tearaway who discovers a mysterious force emanating from beneath a stone circle, while an earlier HTV serial, 1975’s Sky written by Doctor Who regulars Bob Baker and Dave Martin, posited that stone circles could in theory be used as makeshift transmitters by stranded teenage alien entities. These purported transmitting properties would also be explored in a bleaker and very much adult-orientated context in ITV’s 1979 Quatermass revival, and the inadvisability of attempting to move one of the obstinate obelisks was spelt out in no uncertain terms in Stigma, the 1977 entry in the BBC’s long-running anthology A Ghost Story For Christmas. Moyra Caldecott published her ‘Standing Stones Trilogy’ of children’s novels between 1977 and 1978, and on 26th November 1977 the audio track of a news broadcast in the Southern region was hijacked by one ‘Vrillon Of Ashtar Galactic Command’, who might well not have had anything to do with standing stones per se but it is a fairly strong bet that one of the ensuing legion of worryingly fixated Vrillon obsessives will have used one to try and contact him. Although the frustratingly vague and elusive concept of ‘hauntology’ appears to have had many and varied permutations all the way from the psychedelic bands tinkering with nightmarish childhood Victoriana in the mid-sixties to the widely shared early eighties apprehension that Video Nasties could somehow ‘get’ you from beyond the tape – and you can find more of my thoughts on what ‘hauntology’ actually was and how it happened and why here – it is safe to say that in the mid to late seventies, one of its primary manifestations was a wariness of the ancient mystical properties of regional variations on Stonehenge. In October 1978, The Doctor and Romana found that their attempts to locate the third segment of the Key To Time took them to a stone circle in rural Cornwall which doubles as a transmat to an ancient interplanetary space prison, which despite so many other Doctor Who stories from the Tom Baker era in particular being hailed as defining examples of the sort-of genre, seldom if ever finds itself mentioned even in passing in even the broadest and most cursory overview of ‘hauntology’. This is almost certainly down to one simple yet unavoidable detail – it breaks the cardinal hauntological rule by refusing to take itself seriously. There is certainly plenty of superstition, menace and supernatural unease, but there is also The Doctor conducting his own amusingly obstructive intergalactic defence in a barrister’s wig that he just happened to have in his pocket, K9 accidentally erasing all information pertaining to tennis from his memory banks – which would doubtless have engendered a good deal of confusion if he had nipped off to the Boscawen village shop and seen Björn Borg on the front of pretty much every newspaper and magazine in stock – and the utterly delightful no-nonsense eccentricity of Professor Emilia Rumford, whose on-screen dynamic with Tom Baker is so endearing that she honestly ought to have been kept on as a regular character. On face value it might well appear something of a shame that this immensely likeable but routinely overlooked story, while not quite as lacking in prominence as The Ribos Operation, is not afforded additional attention on account of its quasi-hauntological qualities, but the fact that it so casually refuses to fit into any retrospectively imposed bracket is in itself part of what has always marked out Doctor Who as something different amongst its legions of contemporaries, imitators, competitors and sort of semi-associated side projects. It also has the welcome benefit that The Stones Of Blood is just sitting there waiting to be discovered in its own right, free of enforced comparison to its more celebrated and indeed more directly gothic counterparts from before the Mary Whitehouse-necessitated interventory toning down and inevitably being found wanting, and enjoying a rare privilege amongst Doctor Who stories of being able to be judged almost entirely on its own merits. Some of which, it has to be said, pose slightly more questions than others…

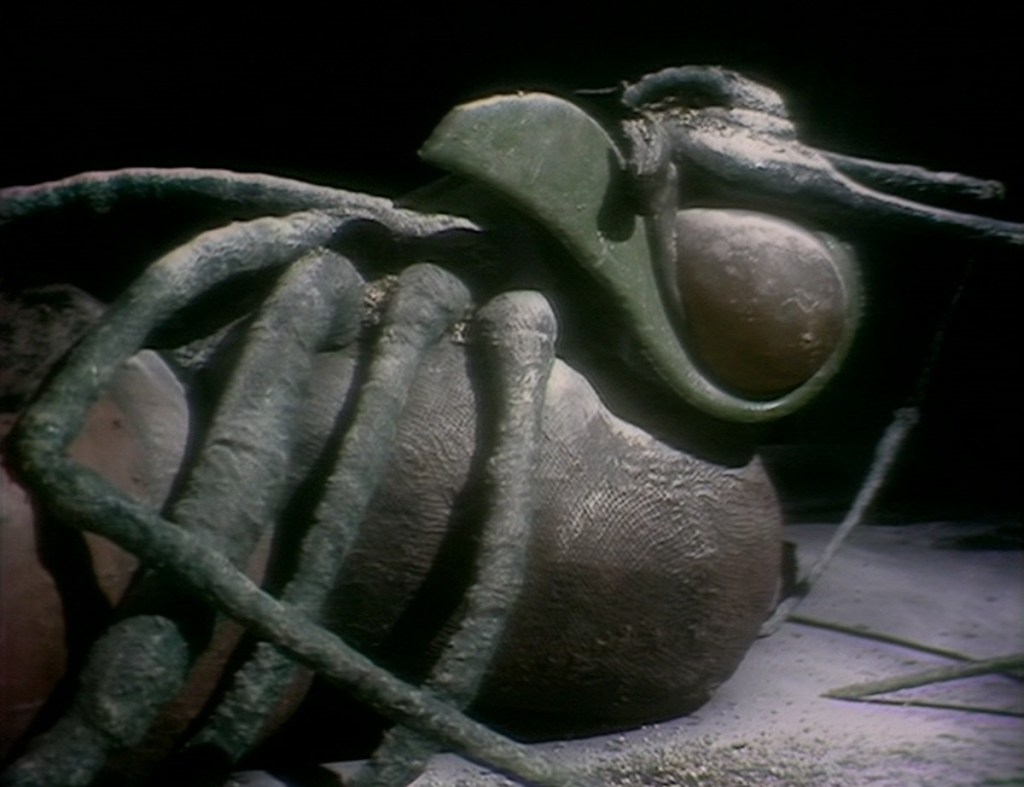

What Had That Wirrn DONE??

One of the reasons why The Stones Of Blood resolutely refuses to conform to any easily enforceable category is the prolonged interlude on board the Megara Prison Ship, which casually combines flashy corridor and blinking light futuristic sci-fi design with acerbic bureaucrat-baiting humour dominated by Tom Baker thoroughly enjoying himself indulging in deliberately time-wasting prevaricatory legal waffle. During this we also get to meet, if that’s the right word, some of the other inmates who have clearly been incarcerated for so long that they would probably consider Blanco from Porridge to be a young upstart including a sort of desiccated relative of the Martians from the film version of The Quatermass Experiment crossed with Nookie Bear, a thoroughly disassembled android of distinctly Kraal-constructed provenance, and the unmistakeable prone form of a Wirrn, last seen bothering the inhabitants of the titular beacon in The Ark In Space. Considering that the Wirrn had spent much of that prior engagement attempting to virulently infest the bodies of human colonists in suspended animation and that this was their presumable everyday modus operandi, you really do have to wonder what this particular insecty miscreant had done that was so far in excess of its expected default crimes against intergalactic law and order and general cross-species notions of taste and decency that it had found itself imprisoned for eternity in its own dedicated cell. We can probably rule out non-payment of overdue fees incurred by having his local library’s copy of the WH Allen edition of Doctor Who And The Ark In Space out for too long, though. He probably knew how it ended.

What’s With All The Romanas?

Positioned somewhere between a lavishly budgeted BBC historical costume drama and a sharp-tongued BBC sitcom set in a workplace where everyone is scheming to use everyone else to their own advantage – or, if you prefer, somewhere between the production values of The Black Adder and the script of Blackadder The Third – The Androids Of Tara is founded on an ingenious if obviously sourced plot which hinges around a procession of spurious doubles and duplicates – robotic and otherwise – that includes Romana, an android replica of Romana and her exact doppelganger Princess Strella continually swapping places at machiavellianistically inopportune moments. This contrivance would appear entirely wholesome and innocent if it was not for the unfortunate and frankly highly dubious ‘coincidence’ that The Armageddon Factor introduces the similarly chicanery-compromised Princess Astra of Atrios, whose physical appearance Romana would summarily adopt as her own at the start of the following year’s run of Doctor Who. As much as this unlikely recurrence of a narrative device would subsequently inspire a relentless stream of incomprehensible letters to Matrix Data Bank asking nothing in particular and eliciting replies that always appeared to be inexplicably missing part of the last sente, when viewed in a less charitable light it really does feel as though we are unwittingly eavesdropping on the Romana-based threesome fantasy of someone somewhere on the production team and frankly that is the sort of thought and image we could well do without. I mean, just imagine if any reasonably prominent commentator on all matters Doctor Who was on record in print and in public saying that what he wanted for Christmas was “two Karen Gillans waving a bottle of Macallan 50”. It doesn’t bear thinking about, frankly. Especially when there were other writers assisting in the search for the Key To Time from a somewhat more philosophical perspective…

…But What’s It FOR?

From best-selling controversial reinterpretations of biblical evidential detail to the animated exploits of Wallace And Gromit to some of the most significant and critically revered revivals of neglected Marvel comic characters, it is fair to say that Doctor Who has benefitted from the involvement of a great many writers who would go on to bigger and if not better then at least more unexpectedly successful things, and the most celebrated of them all – and as the others would doubtless have concurred, deservedly so – was Douglas Adams. Although you really wouldn’t have expected that on his pre-Doctor Who form. Struggling to find a foothold for his absurdist satirical linguistic deconstruction and penchant for ludicrous concepts made casual and mundane through the paper fibre-dulled fingers of bureaucracy, Douglas Adams had spent the mid-seventies as a jobbing gag merchant trying to come up with topical one-liners for The News Huddlines and Week Ending interspersed with occasional stints working as a doorman for visiting dignitaries and oil magnates. Even early patronage from Graham Chapman, who was sufficiently convinced of his talent to persuade the others to use some of his material in the fourth series of Monty Python’s Flying Circus as well as engaging him as co-writer on his solo sketch show Out Of The Trees, did not seem to be enough to provide a career breakthrough. That was until 1978, a year that started with the first radio series of The Hitchhikers’ Guide To The Galaxy and was seen out with the all-star radio comedy Christmas Day panto Black Cinderella Two Goes East – which you can find much more about here, incidentally – and in between, he helped to track down one of those pesky segments of the Key To Time. Witty, imaginative and original – and reputedly Tom Baker’s single favourite script of all time – The Pirate Planet was hailed as distinguished and refreshingly different even on its initial broadcast, and without it we might never have got Wowbagger The Infinitely Prolonged, Dirk Gently, In Search Of The Aye-Aye or the door that says ‘That’s nothing – anyone could have a thing their aunt gave them which they don’t know what it is!’. Meanwhile, as if all of that was not enough, The Pirate Planet also played host to what is possibly the most arresting scene in the entire history of Doctor Who. This occurs partway through episode three, when the Pirate Captain is gloatingly explaining the whys and wherefores of his mechanism for draining all of the energy and resources from unsuspecting planets and the associated ensuing New Golden Age Of Prosperity For All, provoking The Doctor to roar with every last reserve of Tom Baker’s abilities “…but what’s it FOR? What are you DOING? What could POSSIBLY be worth all this?”. Although there are those who will argue, usually with a newspaper column to fill, that Doctor Who has always been left wing and progressive and never anything but that and anyone who says different is a bully who is ruining it for everyone else and probably doesn’t even care about chlorofluorocarbons in their McDonald’s cartons, and those who would counter, usually with an opposing newspaper column to fill, that it has never expressed any ideology whatsoever you silly ninnies being all serious and boring like a big boring bore-o about a fun telly programme with adventure for all and while no they are not right wing and regressive themselves they do espouse evidently right wing and regressive opinions and don’t have a problem with it but that doesn’t mean they are right wing and maybe it is you who is the real right winger not left wing like you think and now you should stop expressing an opinion and just agree with them, see?, but the best manner in which to regard it – and to annoy both of the above – is that it has purely and simply always been against bastardry of all hues and stripes and even over and above “England for the English? Good heavens, man!”, “All… powerful? Crush the lesser races? Conquer the galaxy, unimaginable power, unlimited rice pudding et cetera et cetera?”, “Well now I know you’re mad, I just wanted to make sure” and “It’s been a long time since anyone’s said ‘no’ to you, hasn’t it?”, it is this remarkable six seconds of script and performance that exemplifies and underlines this. Although that all said, it’s no ‘space buns and tea’. The problem with a artistic temperament as exactingly powerfully dynamic as Tom Baker’s, though, is that for every moment of astonishing performing power, you are liable to find another that does not quite exactly achieve those same heights…

Why Does Anybody Love The Armageddon Factor?

Nobody has ever set out to make a bad Doctor Who story – not even The Rings Of Akhaten – and on the occasions when one aspect of production has gone calamitously wrong with no available room or resources for righting it, you will usually find everyone else involved doing their absolute best to steer the ship in at the very least a more broadcastable direction. Black and white stories with meandering scripts where the cast thunder through as if trying to win over a hostile theatre audience. Overlit half-built sets and woeful alien designs thrown into sharp relief by Peter Davison’s bravura insistence on giving his absolute all as if nothing whatsoever is wrong. Even the one or two jokes in The Time Monster are delivered with something at least halfway approaching gusto. If all else had been tried and somehow still just not quite worked out, you could always count on Russell T. Davies to discreetly talk up the aspects that had worked on Doctor Who Confidential. Occasions on which pretty much everyone involved dropped the ball, however, are so rare as to be virtually non-existent, but you would be hard-pushed to find a more exasperating example of pretty much everything falling apart on screen and in real time than in the climactic story of the entire Key To Time saga, The Armageddon Factor. The storyline – such as it is – would barely sustain four episodes but is somehow padded out to six through the addition of all manner of shoehorned diversions ranging from The Doctor shrinking and then not shrinking because of a reason that somebody added at the last minute to the prolonged interludes with The Shadow stumbling around what early Doctor Who fan writers were apparently legally obligated to refer to as his ‘funereal domain’, while the much-threatened Black Guardian appears for literally a couple of seconds as apparently captured on a photo where when you got it back from Boots they’d stuck a ‘Quality Warning’ label on it, and the entire quest for the Key To Time turns out to have been something of a waste of time and effort anyway thanks to a ‘clever’ plot twist that isn’t. To be fair, none of this is especially far removed from what you might well expect to find – or indeed not – in more or less any six part Doctor Who story; what marks The Armageddon Factor out, however is that it honestly does feel as though nobody involved could be bothered. There is nothing in the script, the direction, the design, the performances, the music or even K9’s for once tiresomely perfunctory affirmations and indeed negations that instils any degree of confidence that anyone was particularly concerned about whether they just got replaced by that Temporary Fault caption for the full six weeks. It is in many respects the polar opposite of The Ribos Operation, and while that story may have felt little impact from Tom Baker’s difference of opinion with a dog, by the conclusion of this particular series his frustrations and irritability had spiralled out into a full-tilt management-mediated feud with Graham Williams and it is not exactly unreasonable to suggest that this might have informed the mood in the studio a little. Arguably the starkest and ugliest – and most unashamedly public – manifestation of this can be found in an in-costume appearance on Nationwide by Tom Baker and Mary Tamm while The Armageddon Factor was still in production, in which the former forcefully insults the intelligence of presenter Frank Bough, leaving the latter open-mouthed in an uncomfortably lingering close-up; behind the scenes, however, matters were fragmenting at a frankly alarming rate and Baker actually attempted to relinquish the role between studio recording blocks. Although outside of preserved memos and paperwork none of us can pretend to have any real insight into the breadth and extent of the disagreement and just how genuine any of the threats to derail the series were, it is still true to say that at least on face value, certain of Tom Baker’s demands were impractical and unreasonable if not outrageous, and that you honestly could not hold anyone else accountable for just wanting to do their contracted bare minimum and then go home and try to bag a gig on The Aphrodite Inheritance or My Son, My Son instead. All of which will of course have meant as good as nothing to any of the actual intended audience watching at home and feeling distinctly underwhelmed by what passed for a resolution to the big frantic story arc, but at least they tried. Which, in a paradox that K9 would be proud of, is more than can be said for The Armageddon Factor.

Anyway join us again next time for Brian Wilson’s Holistic Detective Agency, Sapphire And Steel waiting for Count Scarlioni round the back of the bus stop and David Bowie’s ‘Duggan’s Hymn’ EP…

Buy A Book!

There’s lots more about The Book Tower along with Children Of The Stones and tons of other spooky seventies stone-fixated serials in The Golden Age Of Children’s TV, available in all good bookshops and from Waterstones here, Amazon here and directly from Black And White Publishing here.

Alternately, if you’re just feeling generous, you can buy me a coffee here. There’s probably just enough time during that transmission breakdown. Also in the entirety of The Armageddon Factor, to be honest.

Further Reading

You can find more about the mounting animosity between Doctor Who producer and star in It’s Still A Police Box, Why Hasn’t It Changed? Part Sixteen: Marco! Herrick! Terry Lee! Gary Tibbs And Yours Truly! here.

Further Listening

There may be conspicuously little mention of The Armageddon Factor but you can find a look at some long-forgotten Doctor Who-associated spin-off oddities in Doctor Who And The Looks Unfamiliar here.

© Tim Worthington.

Please don’t copy this only with more italics and exclamation marks.