Exactly what happened and why and when and in what order are details that nobody has ever seemed to be quite able to reach a consensus on, but whichever way you look at what happened with Doctor Who immediately after Mary Whitehouse forced the BBC into an humiliating climbdown over the cliffhanger to episode three of The Deadly Assassin – which you find more about here incidentally – it involved one fairly substantial change. Philip Hinchcliffe, the producer who had skilfully and defiantly introduced elements of classic literary horror into Doctor Who and in tandem with his powerfully effective working relationship with Tom Baker had created some outstanding instances of television drama, left the series to be replaced by Graham Williams. The chronology of events has never been entirely clear, and Hinchcliffe for one has always refuted any suggestion that this was anything other than a routine change of producer and that he himself was keen to move on, but one peculiar detail in particular has always left the the whole scenario very much open to speculation. Williams, whose background was primarily in police procedural dramas, had been developing a harder-hitting new detective series for BBC1 starring Patrick Mower and at that point called Hackett. Williams and Hinchcliffe then effectively swapped roles, with the latter renaming the show Target, insisting it should all be shot on location and on film, and kitting it out with a grimy urban funk theme tune and opening titles appearing to depict two Ready Brek-favourers pursuing each other through an episode of Simon In The Land Of Chalk Drawings.

In something of an ironic turn of events, Target would draw a good deal of criticism from observers concerned about its potential effects on adolescent boys watching with elder siblings – which, it should be noted, included several prominent academics – and ultimately from Mary Whitehouse, which Hinchliffe was well placed to face down but even so her lobbying resulted in changes being implemented ahead of the second and final run in 1978. Although Target is now largely forgotten, it did nonetheless mark an important turning point in television history and while they may not quite have shared its enthusiasm for on-screen violence, the show’s willingness to tackle bleaker themes in bleaker surroundings directly paved the way for Shoestring, The Chinese Detective and Juliet Bravo and indeed the many similar shows that subsequently took over their beat. In the meantime, poor old Graham Williams was left with an ageing sci-fi show that he had been ordered in no uncertain terms to tone down without losing any of the audience. Even some of The Doctor’s adversaries never attempted to pull off anything quite so bafflingly and self-contradictorily audacious.

Doctor Who‘s popularity would indeed continue unabated – at least in terms of viewing figures and general enthusiasm from its actual intended primary target viewing demographic – but while he did succeeded in taking a step back from some of the arguable excesses of recent years, Graham Williams appeared to have somewhat less of a sturdy grasp on the tonal consistency, the general standard of visual effects and, most disruptively of all, the show’s increasingly difficult and demanding lead actor. He also had little to no influence over the emerging organised Doctor Who fandom, who quickly proved to have few qualms about objecting vociferously to all of the above and more with an often unnervingly forthright zeal. In some regards, there is even a case for arguing that the long slow path towards Doctor Who‘s cancellation essentially started right here. Although try telling that to a certain last-minute mechanical addition to the regular cast…

“…Affirmative!”

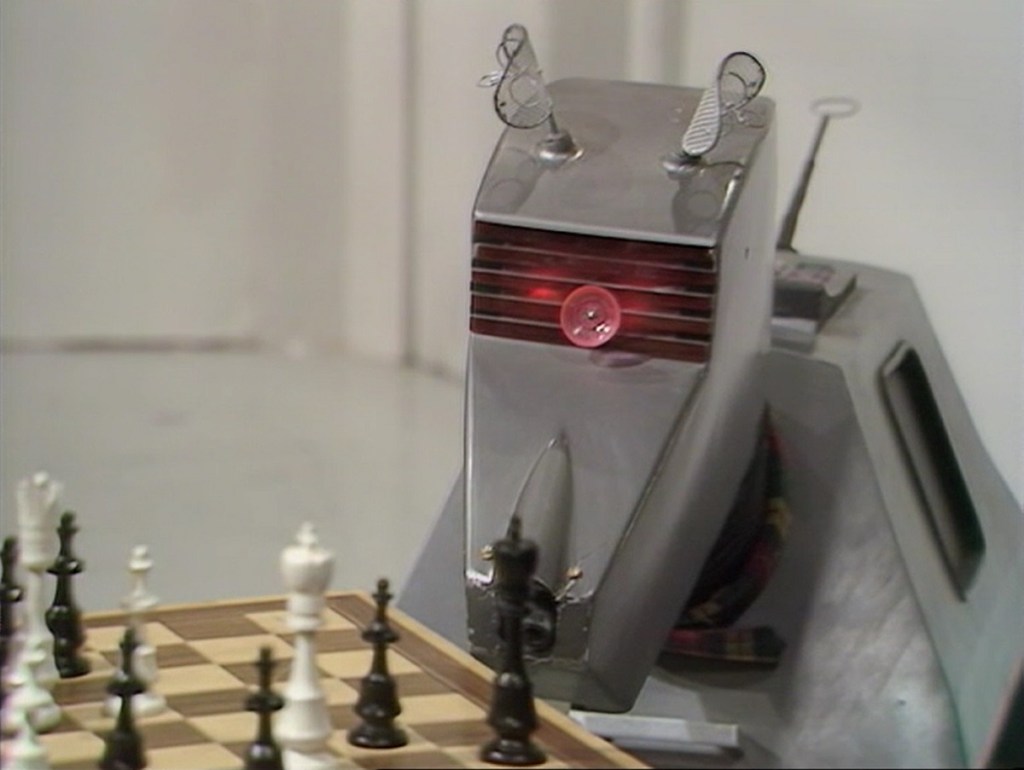

Originally known as FIDO – or Fenomenal Indication Data Observation, in a ‘creative’ approach to spelling that is entirely in keeping with a story that bandies about words like ‘ISOLAYSHUN’ in a presumed bid to appear futuristic that in fact gives more of an impression that it is trying to bag a place in the original line-up of The Cure – mobile mutt-structured computer K9 was originally written in to The Invisible Enemy by Bob Baker and Dave Martin purely as a convenient narrative device to ensure that the storyline was still being conveyed to the audience while The Doctor and Leela were miniaturised and presumably speaking in that ‘goblin’ voice they always used whenever anyone shrank on Rentaghost. Graham Williams, however, saw an opportunity for a novel new regular character, the ‘backroom boys’ saw an opportunity to construct an actual robot dog carefully engineered to veer off in the wrong direction whenever it came within range of a camera signal whilst making more noise than rush hour traffic in a Force 7 gale, and everyone else in the BBC saw an opportunity for it to trundle on to other shows as a ‘mystery’ guest telling Ludovic Kennedy how a plate of oxoric bolts would provide adequate daily sustenance or something. If you were in the market for a new family friendly audience hook to replace the now verboten robot mummies and intemperate brains in jars, then frankly you could not have any greater fortune than to just sort of stumble across an actual robot sidekick who would prove to be both accidentally suited to the imminent outbreak of droid-mania and easily merchandisable for a series that had consistently struggled to inspire a successful toy line. The emergent ‘serious’ fans disliked K9 on account of not wanting to be reminded that what they were watching was made for a huge mainstream Saturday afternoon audience and not solely for the individual benefit of anyone furrowing their brow over how the spines of their Michael Moorcock novels didn’t quite line up symmetrically. John Nathan Turner would subsequently express his exasperation at scriptwriters’ tendency to use K9 to get out of any and every situation, which does suggest that maybe he hadn’t actually paid especially close attention to the actual plotlines. Most witheringly of all, Jon Pertwee would later denounce the hapless robotic dog in quite alarmingly blunt terms because of something about a lavatory in Tooting Bec. To the actual intended audience at the time, however – and it’s worth reiterating that they hadn’t seen R2D2 and C3P0 yet, even spelt as ‘Artoo-Detoo’ and ‘See-Threepio’ – he was an immediately widely loved fixture and even Tom Baker, whilst notoriously dishing out some choice K9-directed in-studio language for the seasonal edification of the ‘backroom boys’, would later come to routinely recall his remote control sidekick with an affection that suggested he had come to view him almost as an actual dog. It might not have been a direction that was quite to everyone’s liking, but you would have a difficult time convincing K9 that his arrival taking Doctor Who in a new direction just when it was needed was anything other than logical. Although sometimes even his most ardent admirers found their patience tested a little…

Pathfinders To… Cassius?

First definitively observed in 1930, Pluto would enjoy its status as the inconveniently Disney dog-adjacently named outermost planet of the Solar System for over seventy years until in 2006, the International Astronomical Union decided that it didn’t ‘count’ like David Bowie’s Deram album. Perhaps anticipating its latterday ignominy, Pluto has rarely ever featured as a fictional setting other than when the occasional pulp sci-fi short story author wanted to go a bit ‘off script’, so its use as the setting for an unsubtle satire of the Inland Revenue amidst an assortment of ugly officious concrete and white tile buildings and omnipresent Consumcards which would doubtless have caused no little consternation to ‘Money’ from the Access adverts in The Sun Makers was and remains incongruous to say the least. Even so, Doctor Who still could not resist the opportunity to throw a further astronomical spanner into the cosmological works, with K9 remarking that it was believed to be the outermost planet “until the discovery of Cassius”, proceeding to reel off further more or less accurate planetary statistics until Leela discreetly gives him a boot-facilitated nudge. Whether or not this public humiliation would have any longer term bearing on the IAU’s still contentious decision to downgrade Pluto is conspicuously unrecorded but given that Gatherer Hade was not actually real, the surprisingly persistent Team Pluto lobby need somewhere to focus their ire. Meanwhile it’s more than a little likely that a generation of erstwhile K9 adherents grew up either being told off for trying to argue that there was a tenth planet in the solar system because Doctor Who said so, or eagerly anticipating an official announcement of its existence that never came. Still, we should probably never have expected better of a series that once somehow apparently forgot the existence of Mercury entirely, although you can find more about that particular cosmological oversight here. Perhaps they might have been better advised sticking with less scientifically informed extrapolations…

“‘Tis Old Fendahl – He Be Abroad!“

Marking the exact halfway moment between the Summer Solstice and the Autumn Equinox in a manner that makes Doctor Who‘s own obsession with the mildest excuses for anniversaries look restrained and unassuming, Lammas – or ‘Loaf Mass’ – is a now largely overlooked Christian feast day which sees congregations process to their village bakery where they celebrate with a quick scoff of the very Brian Butterfield-sounding traditional Loaf Owl With Salt Eyes. As is the wont of such literal feast days, Lammas Eve was long rumoured to be a night when all things supernatural and unholy saw their ‘chance’ and good upstanding citizens who were not safely bolted indoors risked being assailed by Sir Francis Uproar, Eve out of Misty Comic’s The Four Faces Of Eve and the Guild Home Video release of Terror Eyes on Betamax, and this has inevitably given rise to its occasional yet effective deployment as a suitably spooky reference point in all manner of artistic works. It was, as Shakespeare noted, when Juliet turned fourteen, when the Muir-Men win their hay according to the traditional account of The Battle Of Otterburn, and when Reginald Jeeves and Bertie Wooster ran afoul of local superstitions about ‘Old Boggy’, a black-faced demon who is reputed to be ‘walking’ on Lammas Eve, which unfortunately for them is also the exact same ‘eve’ that all of Bertie’s double-barrelled associates from the Drones Club – all of whom had a habit of regenerating between series of the Stephen Fry slash Hugh Laurie adaptation, usually into Martin Clunes – were planning to stage a blackface song and dance show against the wishes of, well, pretty much everyone really. In an absolute turn-up for the books, Inspector Morse also somehow contrived to get a bit narky about Lammas Eve because ‘reasons’. So when local mystic Martha Tyler muttered oblique warnings about ‘Lammas Eve’ to emphasise her sense of the impending onslaught of the titular nihilistic alien energy whatnot in Image Of The Fendahl, in a sense she was merely upholding this grand literary and in turn theological tradition, but it is also difficult not to see it as a safely obscure watered-down version of the trad. arr. folk horror that Doctor Who had been routinely trading in until it all became a little too much for the National Viewers And Listeners’ Association. Literally not quite out of the woods, but also safely enough on the outskirts to know where the nearest National Trust assembly point was. It is something of a shame that they did not explore the Lammas Eve connotations further, though, as it would have been fun to see K9 take on ‘Old Boggy’, or at least find himself represented in loaf form in an hilarious episode-closing gag that wasn’t. Although it’s not unreasonable to suggest that he already had more than his fair share of edible representations as it was…

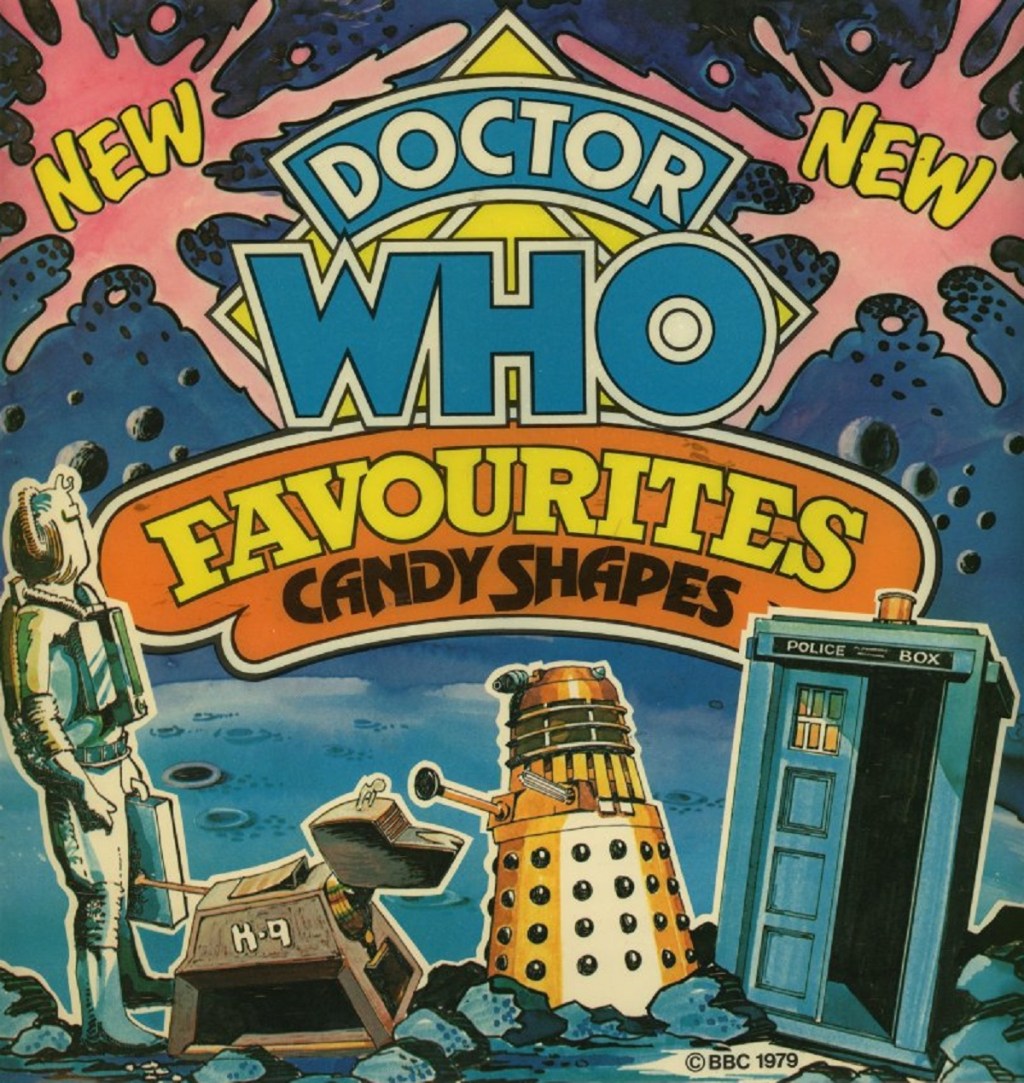

Goodies Goodies Yum Yum

Although understandably few examples still exist, unless there is some obsessive fan somewhere with their own cryonic vacuum-sealed ‘Doctor Who Bunker’ preserving mint condition mint-flavoured Daleks Death Ray ice lollies in suspended animation whilst also protecting the entire print run of The Doctor Who Halloween Book against the not especially book-affecting ravages of everyday environmental conditions, there has been Doctor Who-related confectionary for essentially as long as there has been Doctor Who itself. From the Dalek Sweet Cigarettes that the ‘woke’ brigade won’t let you have any more because apparently furiously shouting at children that boring chalky sticks of nothing that nobody especially liked and lost all cultural relevancy decades ago are their ‘favourite’ no arguments is frowned on now and the doubtless adhering-to-the-wrapping-er on the inside TARDIS toffee, through that plain ordinary chocolate bar only it came with collectable cards with The Master in Avenue Q or something and the not as exciting as it sounds ‘Invasion Of The Daleks’ Easter Egg, all the way up to that Comic Relief bar where David Tennant appeared in the guise of James Marsters if you held it up to the light and that entirely canonical Cyberman Head Full Of Sweets, there has never been any shortage of ways of convincing yourself that you were somehow ‘helping’ your favourite ailing sci-fi show by shovelling yourself full of sugar. Few enjoyed such scoffably iconic stature, however, as the series of Doctor Who ‘Candy Shapes’ issued by the suspiciously conveniently-named Goodies in 1978. Consisting of white chocolate approximations of a Cyberman, a Dalek, the TARDIS and K9, the handspan-challengingly oversized comestibles were repackaged over the next couple of years in a bewildering array of permutations including portrait and landscape oblong boxes, Christmas Tree decorations, tubs of festive sweet assortments and probably even distributed directly from Tom Baker’s unpredictably capacious pockets and were a regular sight in all halfway decent party bags. Although it was far from unusual for popular television programmes to inspire their own range of chocolate shapes – and if we were to suggest that Doctor Who was any kind of special case then Dill The Dog might want ‘a word’ – the sustained popularity and market saturation of these Target Book cover illustrations made edible does at least underline just how much, even during this most unfairly maligned of eras, Doctor Who was part and parcel and party parcel of everyday discourse for a wider younger audience in a way and to an extent that it would soon semi-intentionally lose and take decades and more than one relaunch to find again. What kind of conjurer of a master chocolatier could possibly have come up with such thrillingly vague Police Box approximations, though…?

Come With Me, And You’ll See, A Story That’s Not Filmed On Location

Poor old Underworld. A worthy and wordy and thoroughly uneventful story about a scientific slash archaeological linear expedition fuelled by the mantra ‘the quest is the quest’ – the quest in question being to find, well, a mega mega white thing – the entire four part story was conceived as a book-balancing exercise that would not even require actual sets, with the majority of the action being performed against blue backdrops with appropriate model and artwork scenery cued in via the wonders of Colour Separation Overlay. While the overall effect and indeed effects is not quite as bad as shrieking posturing fans who have confused snark with having an opinion might have you believe, it would still be something of an understatement to say that it did little to enhance whatever there actually was of the on-screen action, and a proliferation of protective headgear that only a couple of years later would have had the majority of the viewing audience asking ‘What’s Mr. Chips doing?’ does not exactly help much either. Unloved and uninteresting, it is the closest that Doctor Who ever got to filing your building society statements. There is, however, one moment of changed pace and levity, when The Doctor, Leela and helpful moderately non-subservient youngster Idas elect to travel to the centre of the unnamed planet – which presumably wasn’t Cassius – and towards the fabled P7E by means of ‘The Tree At The End Of The World’, or in less fanciful terms a sort of long Cream Soda-lined shaft characterised by a pronounced lack of gravity. Taking the opportunity to make a handful of sorely needed quasi-satirical wisecracks, they drift gently downwards to the accompaniment of twinkly muzak looking suspiciously as though they have consumed whatever the opposite of Fizzy Lifting Drinks are. Unfortunately what is waiting for them at the other end is not a stroppy bloke in a purple velvet jacket and a collapsing top hat but essentially some complicated insurance forms with dialogue but it was nice while it lasted. Anyway, it’s not as if this particular series of Doctor Who was exactly overrun with memorable adversaries…

Get No Kicks With Rutan 1906

Perhaps suggesting that Graham Williams had understood his brief more closely than is usually considered to be the case, Horror Of Fang Rock, the opening story of the 1977 series of Doctor Who, is much more aligned to the worrying excesses of recent years whilst also being a very definite and much needed step away from them than it is ever given credit for. Set aboard a turn of the Twentieth Century lighthouse where the crew and some escapees from a passing stricken luxury yacht – sadly not pronounced as ‘wobbler mangrove’ – find themselves drawn into a murder mystery that The Doctor and Leela cannot help but suspect may involve forces beyond the fanciful imaginings of Mary Elizabeth Braddon. It is an ominous and unrelenting thriller told with claustrophobic flair and other than the absence of Mary Whitehouse-alarming outbreaks of violence and gore, you would be hard pushed to categorise it elsewhere other than alongside The Brain Of Morbius and Pyramids Of Mars. There is even a decent surprise for longer-term viewers as it transpires that the Marple-anticipating chicanery is in fact the consequence of the efforts of a stranded Rutan, the frequently referenced but never previously sighted shape-shifting arch-enemies of The Sontarans, with whom they have been locked in a vainglorious interplanetary war that may in fact have been in a furiously contested stalemate for centuries. When The Doctor confronts the unshapeshifted Rutan on the stairs as if consoling it after being dumped at a party, however, what the audience sees is not an imposing adversary worthy of the celebrated stocky squat clone warriors but a sort of dazzlingly lit glob of overtoasted cheese liberally infused with limeade that even Colonel James Skinsale MP would have laughed out onto the rocks, let alone Weam Styre and company. All in all, then, it’s a good job that the Rutan wasn’t the most terrifying interloper that the inhabitants of Fang Rock would have to contend with…

“My Brother Is Wearing The Other One…”

While The Doctor is wittering away to that Rutan about whether Stay Together should have been on Dog Man Star or not, we’re going to be sidling in to the TARDIS and taking a discreet trip forward in time to 1987. 22nd November 1987 in fact, because that was when, roughly eleven minutes into a repeat broadcast of episode one of Horror Of Fang Rock, Chicago-area Public Broadcasting Service station WTTW was interrupted by persons unknown calling sports broadcaster Chuck Swirsky a “frickin’ liberal”. This was The Max Headroom Broadcast Signal Intrusion Incident, and having already pulled off a vision-only disruption of a sports roundup on rival local broadcaster WGN for around twenty seconds, prompting bewildered anchor Dan Roan to splutter “well if you’re wondering what’s happening, so am I!”, the transmission hijackers toting a rubber mask of Channel 4’s well-known fictional transmission hijacker then succeeded in knocking Horror Of Fang Rock off the air for a full minute and a half of pop cultural non-sequiturs, shade thrown at ‘New Coke’ and some light satirical BDSM. Exactly who pulled off this staggering technological feat, and indeed how they did it and why, remains a much speculated-on – and arguably possibly too deeply speculated-on – mystery. Parodied everywhere from Agents Of S.H.I.E.L.D. to The Den, the bizarre blast of distorted audio and video has arguably enjoyed an even greater cultural footprint than Max Headroom himself, and it is pretty much guaranteed that if you mention it anywhere in any context, your replies will instantly fill up with complete strangers demanding you watch their two hour video about it. What is more interesting than witless ‘deep state’ speculation, however, is that the putative computer generated television host from twenty minutes into the future’s popularity had peaked in the UK in the previous year, when he had his own best-selling computer game, coffee table book and hit single in cahoots with The Art Of Noise which is frankly both too tuneful and too funny to be designated ‘novelty’, and a high profile Christmas Special of his Channel 4 show, which also gave rise to its own festively-themed pop disc; despite being genuinely really good, however, it failed to trouble the charts too much – perhaps indicating his moment of mass popularity was on the wane – although you can hear much more about that here. The Channel 4 show had been shown on American cable network Cinemax, though, leading to ABC expressing an interest in repositioning Max as the star of a sci-fi comedy action series based on the original 1985 introductory pilot one-off which ran for two series between 1987 and 1988, which was presumably where these elusive scamps came in. If you really want to know more of my thoughts on The Max Headroom Broadcast Intrusion Incident then you can hear Grace Dent and myself having a chat about it here, but for the moment there is only one other surprisingly little-acknowledged aspect to the whole phenomenon that needs to be noted – that it has somehow tied this most unassuming of Doctor Who stories, Rutan and all, in with one of the most notorious and obsessed-over unexplained mysteries of the Twentieth Century. Let’s see your Love And Monsters do that. As for that distorted audio, however, let’s just say that it would not have sounded out of place on a certain record sitting in the New Releases racks as we arrive back in 1978…

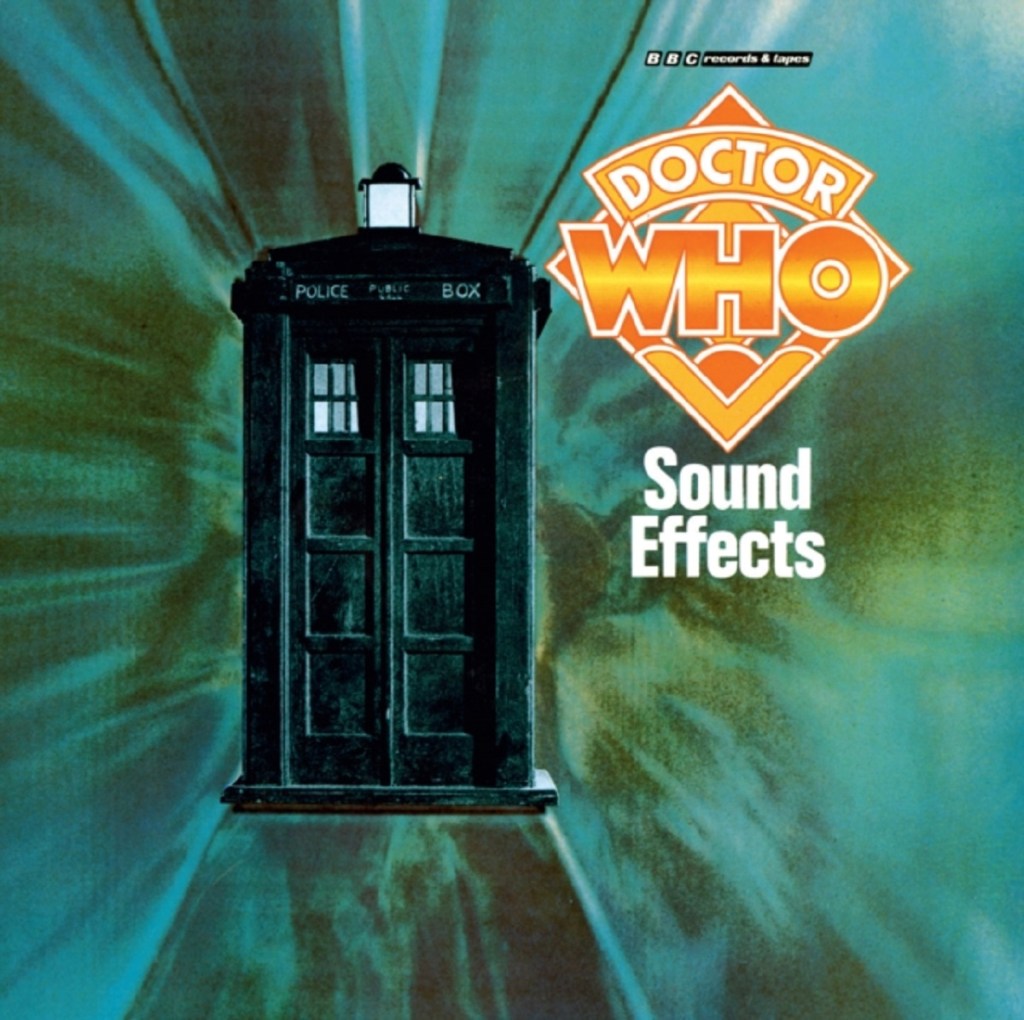

Kraal Disorientation Chamber

Commencing with RED47 Sound Effects No. 1 in 1969 and continuing right through to the appropriately themed REC531 Hi-Tech FX (Sound Effects No. 29) in 1984, BBC Records And Tapes would issue almost three dozen collections of crashes, bangs and wallops – and bleeping spaceships, bubbling test tubes and windows that sort of played a tinkling symphony as they shattered offscreen while Terry Scott looked on aghast – drawn from their Radiophonic Workshop-furnished sound effects archive, intended for use in amateur dramatics and other similar creative ventures. Along the way, if you were so inclined, you could have seen fit to enhance your staging of An Inspector Calls with Footsteps To Water Then Splash, Electronic Swamp, More Or Less Normal Chicken, Boiling Oil Poured Off The Castle Wall, A Huge Ever Growing Pulsating Brain That Rules From The Centre Of The Ultraworld and, of course, Man Punches Wasp In Eye. Mary Whitehouse attempted to get 1978’s Sound Effects No. 13 – Death And Horror removed from high street stores as you can hear much more about here, Paul Weller was sufficiently enamoured of the series to ‘borrow’ the title and the generic cover design for a certain album although he stopped short of covering Hawker Harrier Vertical Take-Off (1969), and the imprint even got its own ‘Greatest Hits’ of a sort in 1982’s Essential Sound Effects. Although if you really want to know more about this peculiar collection of records then you would do well to invest in Top Of The Box Vol.2, the story behind every album released by BBC Records And Tapes, which is available in paperback and for Kindle from here. Some of the releases in the Sound Effects series were nominally ‘themed’ collections, even if on occasion the contents did challenge the definitions of thematic coherence slightly, and in 1978 fans finally got the opportunity to stage their own multi-Doctor ‘reunion’ story in the comfort of their own shed with the release of Volume 19, Doctor Who Sound Effects. This wasn’t the first time that Doctor Who had shown up on a sound effects album, with a handful of early seventies effects jostling for space with the full-length TARDIS dematerialisation on the general sci-fi themed Out Of This World and an unbilled ‘insect swarm’ from The Invisible Enemy finding its way onto Sound Effects No. 19 – Disasters, but this presented a full set of series-derived electronic stings drawn from stories stretching as far back as Death To The Daleks and as recently as The Invasion Of Time, although many of them were confusingly identified by the working titles hastily scribbled on Radiophonic Workshop tape boxes, so good luck to anyone trying to work out why ‘Dr. Who And The Exxilons’, ‘The Curse Of Mandragora’, ‘The Destructors’ and ‘The Enemy Within’ were missing from their collection of Target novels. You may well be musing that this does not exactly sound like the most listenable long player in the history of recorded sound and indeed it wasn’t – but even so, listen to it is exactly what people did. There was one other Doctor Who album available at the time of release and even that had little in the way of what could justifiably and legally be considered ‘music’ on it, and no way of owning any video material at all, so if you wanted to revisit the thrills and spills of late Saturday afternoons in your non-Who time, then listening to Sutekh Time Tunnel and Fission Gun (2 Blasts) in the correct linear sequence it was. There is a reason why the album is held in such affection and was even reissued on CD – albeit without that ‘insect swarm’ as a bonus track – and it is perhaps the most powerful evidence we have that Doctor Who fans or indeed fans of anything full stop once appreciated what little was available to them on a more straightforward level. It’s certainly worth bearing in mind the next time that someone posts angrily on a forum that your extended look at The Box Of Delights in its original context is ‘overwritten’. Anyway, it’s not like there weren’t other actual records at your disposal with actual music on them and everything…

Send It Off In A Letter To Yourself

Released as the lead single from their breakthrough 1974 album Pretzel Logic, Rikki Don’t Lose That Number was the first top five hit for the defiantly studi0-based jazz-rock band Steely Dan, winning them effusive praise from no less an authority than John Lennon. Widely misinterpreted on account of their tendency to rely heavily on cryptic and allusive lyrics elsewhere, it is in fact, as songwriters Walter Becker and Donald Fagen were frequently called on to recount with tangible weariness, simply a song suggesting to someone who had turned you down for a date that they might want to give you call if their other options end up not working out. That was in America, however – in the UK they would remain very much cult favourites until much later in the decade, and while Rikki Don’t Lose That Number was a noted favourite of Radio 1 DJs desperate to position themselves as men of musical taste, it stalled some way short of the top seventy five when released as a single. Intentionally designed to take advantage of massive leaps in quality in home entertainment systems, the rapturously received Aja suddenly began to sell in huge quantities in the UK late in 1977, leading to a rush of demand for their earlier albums, an inevitable Greatest Hits collection, and Rikki Don’t Lose That Number itself climbing back up the charts to only narrowly miss the top forty. Whether or not Bob Baker and/or Dave Martin had found themselves with a Steely Dan-derived earworm when inserting a line of dialogue instructing Minyan communications officer Tala “don’t lose that signal!” into Underworld will have to remain a matter of conjecture, but even so, the fact remains that this is a textbook example of the seemingly limitless list of potential external direct and indirect cultural influences on Doctor Who that fans of Doctor Who habitually refuse to countenance simply because they aren’t Doctor Who. The irony of course is that many of them presumably do like Bellal’s pin shot, and they keep it with his letter, done up in blueprint blue, it sure looks good on, erm… him? In any case, there is one story right at the end of this particular run of Doctor Who that demonstrably responded to a wider trend in popular culture in a manner that frankly you would have to be a dedicated hardline Doctor Who absolutist contrarian to the point of dullness to disregard…

Saturday Super Stor

As any Doctor Who fan will doubtless vigorously confirm, The Invasion Of Time is a thrillingly flawed and ambitiously overlong six-part everything-including-a-kitchen-sink – yes, you can see one in one of those corridors – story full of spectacle and narrative twists but relying on a double double double bluff that requires the audience not only to believe that The Doctor would suddenly go ‘evil’ for no obvious reason but also that The Sontarans would tolerate deploying frankly quite useless sliver of Bacofoil left on the end of the roll second tier adversaries The Vardans as part of a plan to infiltrate Gallifrey on their behalf instead of just proudly thundering in themselves, that an eighteen episode long chase sequence might take place ‘inside’ a TARDIS filled with corridors from the dentist’s and the world’s most boring swimming pool, and that after taming a tribe of feral exiled Gallifreyans and rousing girly girl Time Lady Rodan into assertive and direct action, Leela’s next obvious move would be to insist on remaining behind and forcibly marrying the disconcertingly Ace Rimmer-like Commander Andred. To any actual youngster watching it in 1978, however, all of this was the best thing ever and exactly what they wanted to see on a Saturday afternoon and they drew some Sontarans afterwards to prove it. It is also, frankly, such a jumbled assortment of ideas that it can only realistically inspire a jumbled assortment of thoughts and observations about it, so that’s exactly what you’re getting here. Although Leela’s mode of departure may have been a surprise to say the least – even if they do try to work around the out of character aspect to it with some halfway decent dialogue, albeit nothing anywhere near as memorable as “you touch me again and I’ll fillet you” – Louise Jameson’s decision to leave the series perhaps is a little less difficult to understand. Even aside from an initially fractious working relationship with Tom Baker, she had also spent her first year in the role wearing uncomfortable tinted contact lenses – only removed at the conclusion of Horror Of Fang Rock with the explanation that the Rutan-trouncing explosion was so bright that it had changed her iris pigmentation – and found herself having to contend with wildly inconsistent characterisation from story to story, but overall she made a huge impression and precipitated an enormous change in what viewers might have expected of Doctor Who and on balance Leela was substantially more progressive than not. It is probably no quirk of coincidence that once she left – sadly Louise Jameson did not walk straight into a role in Target, thereby denying us some neat symmetry or at the very least an excuse for a joke – they replaced her with a character who was as fearless and ruthless intellectually as Leela had been physically. K9 also technically ‘left’ with Leela, and it seems that for a while at least this was actually planned as the Bonio-favouring mobile calculator’s departure from the series too, only narrowly winning a reprieve courtesy of a closing scene where the camera hones in on a box labelled ‘K9 M II’ and Tom Baker looks directly into the camera and directly at the audience with a grin that suggests for all the world he is about to start babbling “that does it… he’s a frickin’ nerd!”. This new improved K9, very carefully constructed by the ‘backroom boys’ to avoid the remote control-occasioned technical headaches of the previous iteration, was indeed to continue to feature in Doctor Who, and while his original appearance might well have preceded the Ask Aspel-troubling rise of R2D2 and C3PO over here, the decision to keep him on was almost certainly at the very least partially informed by their sudden elevation to Christmas List dominance. K9 is both an idea that proved Doctor Who could function independently of wider trends in popular culture and one that underlines its dependency on those wider trends too, a logical contradiction so irresolvable that it would probably cause him to do that thing where he spins round saying ‘NOT – TRIGONOMETRIC’ or something, doubtless to the consternation of Russell Harty. It’s almost like nothing stated or asserted at any point in this ramble about the 1977 to 1978 series of Doctor Who has actually made any coherent or correlated sense at all. Hang on a minute, just got to take this call from Tala…

Anyway, join us again next time for John McEnroe facing Vivien Fey in the US Open, the Swampies’ Canned Corn sideline and why Kroll ended up getting two hundred lines from Mr. Withit…

Buy A Book!

You can find much more about Doctor Who Sound Effects and many more even more bafflingly unlistenable records of debatable commercial potential in Top Of The Box Vol. 2, the story behind every album released by BBC Records And Tapes. Top Of The Box Vol. 2 is available in paperback here or from the Kindle Store here.

Alternately, if you’re just feeling generous, you can buy me a coffee here. Don’t be alarmed if the picture starts to break up while you’re getting it, though…

Further Reading

You can find more about the furore that led to both Doctor Who and Target effectively switching pre-transmission identities in It’s Still A Police Box, Why Hasn’t It Changed? Part Fifteen: Borusa, Borusa, Borusa Ja Ja here.

Further Listening

You can find a chat with Grace Dent about The Max Headroom Broadcast Signal Intrusion Incident in Looks Unfamiliar here. We don’t really mention Horror Of Fang Rock in it. But we do mention Chas’n’Dave…

© Tim Worthington.

Please don’t copy this only with more italics and exclamation marks.