One week late in November 1984, the front cover of Radio Times proudly proclaimed that “a spectacular new children’s serial starring Devin Stanfield” – enticingly described as a “fantasy with fantastic effects” – was about to ‘open’ on BBC1. This was The Box Of Delights, a six part serial based on John Masefield’s 1935 novel adapted by Alan Seymour, directed by Renny Rye and produced by Paul Stone, and frankly it is little wonder that the BBC were taking such prominent pride in it.

The culmination of a series of stylistic and technological advances that the BBC’s Children’s Department had been quietly but steadily making over the past decade, The Box Of Delights – which several of the key figures on the production side had been agitating to adapt for most of that decade – was marked out by a distinguished cast including for once a more than capable roster of child performers, stunning visual effects that blended traditional animation, lighting and puppetry with state-of-the-art video manipulation, and an outstanding score by Roger Limb of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop. It was essentially no more of an epic production in terms of its actual production than any of the similar serials that had preceded it, but it was nonetheless a fascinating and challenging one strewn with odd and unlikely coincidences and the end result was an unqualified triumph of ambition and imagination over resources, although you can find much more about the actual making of The Box Of Delights in The Golden Age Of Children’s TV here. Perhaps unsurprisingly, The Box Of Delights went on to win an unprecedented haul of industry awards for a children’s television programme, and would ultimately come to be hailed as something of a landmark production, cited by critics and viewers alike as an exceptional example of the highest achievements of the medium and so widely loved that it inspired a longstanding tradition of annual rewatches on the original broadcast dates. It was old-fashioned without being sentimental, it was thoroughly contemporary without dispensing with archaic fashions and references, and it was above all frostily and tinselly Christmassy in a paper chain-strewn sense of the season that was already rapidly retreating into a past only substantially preserved by illustrations on Christmas cards and biscuit tins, and frankly it is not altogether surprising that it continues to be held in such high and fond regard.

Although that is not quite the full story. As much as mentioning this might draw immediate and indignant retorts that it was an instant ‘classic’ round at your house, I think you’ll find, The Box Of Delights was made as a children’s television serial and received as a children’s television serial, and for a long time enjoyed essentially as much prominence and acclaim as pretty much any other children’s television serial. It may have met with a rapturous reception on broadcast, but – as with more or less any other television programme, children’s or otherwise, in what in itself is now in some senses a long-lost world – it was neither made nor conceived with longevity in mind, and following a repeat in three omnibus format instalments in the run up to Christmas in 1986, The Box Of Delights was quietly stored away with the cardboard boxes of old-fashioned Christmas decorations. Barring an elusive and expensive BBC Video release, it was not available in any format for many years thereafter, and anyone wanting to stage an early attempt at a festive rewatch had to resign themselves to playing the theme single – which wasn’t even the same as the version of the theme tune used on screen; there’s more about that here incidentally – whilst staring at the notoriously shoddy cover of the tie-in paperback edition of the original novel. In case you were about to challenge that yet again on the grounds that it was always a ‘classic’ and also you mentioned Foxy-Faced Charles once and someone sort of possibly knew what you were talking about maybe in a vague roundabout manner, handily there is a very lengthy chat with Stephen O’Brien about what it was like to find yourself in search of The Box Of Delights during those lost years when it was stranded in the past like Arnold Of Todi in Looks Unfamiliar here. Of course, that affection and acclaim was simply too powerful for it to remain overlooked and unavailable for long, but nonetheless there genuinely was a time when, to all intents and purposes, The Box Of Delights honestly held no more cultural prominence or significance than White Peak Farm, The Witches And Grinnygog or How To Be Cool. Although it always held more prominence and significance than The Country Boy. There are limits.

Nowadays, of course, The Box Of Delights is available on a brand spanking new Bluray, enjoys seasonal repeats more often than it doesn’t, embarks on occasional similarly seasonal cinema screenings in its entirety and preserves a tradition entirely of its own with those endearingly embraced mass rewatches. As welcome as all of this is, however, there is one crucial aspect of The Box Of Delights that none of these are really able to recapture. They are all founded on a retrospective view of a serial that we have come to accept as, well, a television ‘classic’ – but what was it actually like to watch it on that original broadcast, when all you had to go on ahead of transmission was that scattered handful of not especially informative Radio Times features, a behind-the-scenes item on Blue Peter and the occasional even less informative mention in John Craven’s Back Pages? How can we possibly beat Abner Brown at his own game and find some of that ‘old magic’ for ourselves, preferably without having to circumvent grog-swilling ‘pirate rats’ along the way? Well there’s only one way we can really, and that’s to follow Kay back in time and try to watch it with a sense of context, a lack of expectation, and indeed a sense of what it was like when The Box Of Delights really was just another children’s programme…

Episode One – When The Wolves Were Running (21st November 1984)

It’s a cold yet oddly weather-averse late Wednesday afternoon as the nights, as elderly relatives chatting to random fellow passengers on the bus are wont to remind you apropos of very little bar the already plainly obvious visible evidence, are drawing in. The nation’s schoolchildren, meanwhile, can almost just about see the faintest tantalising glimmer of the Christmas Holidays on the horizon, but those crucial three weeks sat between you and the possibility of there actually being a couple of Matchmakers left in the box by the time you are allowed anywhere near it still feel as hopelessly and frustratingly distant as a Nineteenth Century illustration of the Nativity. Chaka Khan is at the top of the Top Forty with I Feel For You, a startling and infectiously fresh electro-funk return to form written by Prince and introduced by a famously imitable rap from Melle Mel, which despite straddling about eight different mid-eighties genres at once even now still sounds as if it was recorded yesterday. Unsurprisingly, it isn’t a record that’s about to go anywhere in a hurry, but all that might be about to change abruptly; upset and angered by a BBC news report about a deepening humanitarian crisis in East Africa, Bob Geldof is placing a series of no doubt expletive-strewn phone calls to fellow pop stars urging them to turn up at Sarm West Studios in Notting Hill on Sunday Morning. Perhaps suggesting that a repositioning of their output might well be on the horizon, the threadbare Children’s BBC schedules today can only offer Brian Cant – who was also presenting that day’s edition of Play School – reading Jan Mark’s Handles for Jackanory, the worryingly titled Superted escapade Spotty And The Indians, the ailing and outmoded Screen Test balancing the alleged excitement of second-tier Disney clips against Young Filmmaker Of The Year entry Chess by Jonathan Agnew – presumably not that one – and the inevitable update from John Craven’s Newsround. Right at the news-buffering tail-end of the timeslot, however, was something more than a little different…

Bemoaning the fact that the hasn’t a tosser to his kick – earning him a slang-disapproving rebuke from his guardian Caroline Louisa for his troubles – young Master Kay Harker is on his way home from school for Christmas. On the station platform he encounters Cole Hawlings, a ramshackle Punch And Judy performer who replies in cryptic positivities and also seems to be able to conjure up duplicate tickets from nowhere and for no clear purpose, and on the train itself he encounters a couple of exceptionally shifty ‘clergymen’ with a penchant for card games and somewhat less of a welcoming disposition towards dogs gawping through carriage windows. Back at Seekings after a quick stop for muffins, Kay is moderately concerned by the presence of the four Jones siblings as guests for the holidays on account of the fact that there is rather a ‘gollop’ of them. Mr. Hawlings drops by to give the assorted expanding gollop of local youngsters a puppet show before quietly confiding in Kay about a mysterious box in need of safekeeping which grants its holder the ability to go swift, to go small, and apparently to see an animated phoenix in a fireplace, before strolling off into a painting without really properly explaining who or what it needs safekeeping from. Kay finds his answer when he stumbles across the sinister clergymen in conference with an even more sinister clergyman and a sweaty human-sized rat driving a hard informational exchange bargain in a bid for ever-increasing quantities of green cheese. Then, by way of something to do with an old woman with a gleaming ring, Kay finds himself mounting a flying horse and is propelled into the middle of a pitched battle in an Iron Age encampment besieged by wolves…

Even if you had somehow managed to avoid that week’s issue of Radio Times – or if it had vanished instantly from the front room only to mysteriously re-emerge the second it was consigned to ‘last week’ status – you still would not have been short of exhortations to tune in to The Box Of Delights. Blue Peter had run a lengthy preview feature on 19th November, with Janet Ellis joined in the studio by an in-costume Devin Stanfield as Kay Harker and Simon Barry as Mouse and a resolutely out of costume Patrick Troughton, with the closing credits rolling over the faintly disturbing sight of Mouse stroking an atypically docile Jack the cat. Devin also showed up alongside scriptwriter Alan Seymour on Pebble Mill At One earlier on 21st November, and a notably confident and attention-demanding trailer had been showing up all over the BBC schedules and quite possibly receiving more airings than those of Comrade Dad, The Prisoner Of Zenda and Big Deal combined. Even aside from that, a huge number of BBC magazine shows had been hyping it up by using possibly the least enticing clip possible, though more about that when it shows up in the series itself. Everyone involved appeared to have every confidence that they had something spectacular sitting on their shelves ready to roll, and they were not wrong about this.

The opening titles of The Box Of Delights, with Roger Limb’s ingenious reshaping of The Pro Arte Orchestra’s 1966 reading of the third movement of Victor Hely-Hutchinson’s Carol Symphony – which you can read much more about here, incidentally – twinkling mysteriously over manipulated images of various characters from the serial, including a genuinely quite eerie flash of lightning across Abner Brown’s face, are rightly and regularly celebrated, and make it clear from the outset that more effort, imagination and determination has gone in to this than many other Children’s BBC productions of the time. Where God’s Wonderful Railway may have just reached straight for the sepia photographs and off-the-shelf library music, this is a direct assertion that everyone involved wants to let you know exactly what to expect; and whatever that is, it’s certainly not going to be the Grant family arguing over what the new platform extension might look like. There is another way in which The Box Of Delights is marked as something different right from its opening scene, however. No matter how authentically true to the thirties the fashions, vocabulary, modes of transport and even shop counters may be, the setting still manages to feel thoroughly contemporary to an extent where it would not seem especially out of place on television even now. Skilfully directed and recorded entirely on videotape, and taking great care to make its painstakingly recreated period detail secondary to the actual storyline and performances, it somehow looks like it is taking place in the world as we recognise it, rather than intentionally immersing itself intangibly in the past. In this sense it succeeds in connecting with the audience in a manner that so many other similar productions from around the same time, from the Doctor Who story Black Orchid and The Box Of Delights‘ own contemporary in the Children’s BBC spooky run-up-to-Christmas serial slot A Little Silver Trumpet – which you can find more about here – to wartime board-treading light drama Bluebell and the BBC’s superlative series of Miss Marple adaptations which would launch on 26th December 1984 with The Body In The Library, neither particularly wanted nor were particularly able to. Where they were content to define themselves as taking place in the past, and more than happy to use more expensive-looking but aesthetically remote film for their location sequences, The Box Of Delights feels like it could be taking place around an admittedly chronologically displaced corner on the streets as we know them right now. That is almost certainly a huge part of the reason why The Box Of Delights found such a willing audience, although not the only one. It is such a huge one in an entirely different sense, however, that it has already taken up more than can possibly be realistically afforded to a concise overview of a single episode of a six part serial, so further musings on Roger Limb’s soundtrack, Miss Mariah, Foxy-Faced Charles and Chubby Joe, just how green cheese “as green as only you can eat” would actually have to be and the recurring instances of narrative lurches that make little to no sense – this episode does, of course, conclude with the excursion into that mid-skirmish encampment that really does just seem to come from nowhere – will just have to wait for now. Well come on, Cole Hawlings did only say you may see something of the box, didn’t he?

Episode Two – Where Shall The ‘Nighted Showman Go? (28th November 1984)

The Christmas Holidays may be drawing closer, but whether any of the schoolchildren ostentatiously leaving the Grattan catalogue open at the toy pages with Transformers and/or Pound Puppies skewed determinedly parentwards like it or not, it is technically still November and they could not feel impossibly further away. Perhaps in tacit acknowledgement of this interminable frustration, today’s Children’s BBC schedules are seemingly infused with a touch of defiant silliness, all the way from the See-Saw slot playing host to a double-bill of geriatric Postman Pat expanded universe antisocial menace Gran investing in a camper van and doubtless driving it around at reckless speeds and, appropriately enough, high-speed urban hallucinatory machines-at-work soft-rock bellowing-prefaced documentary strand Stop – Go! (which you can hear a chat about on Looks Unfamiliar here) pulling up in the world of the ‘All-Wheel Drive’, while over on BBC2, Play Away‘s updated – i.e. it mentioned McDonald’s and Indiana Jones – sketch show successor Fast Forward had elected to present its Radio Times billing entirely in their invented language ‘backslang’, which essentially involved switching the first letter of a word to the end of it and then appending a random ‘a’. It’s probable that most readers simply mistook it for a misprint. Chaka Khan is still at the top of the pop charts, although two days earlier, following an all-day recording session on 25th November that basically involved corralling a baffling assortment of chart stars into singing randomly assigned lines of a song urging support for famine relief and then recording cheery festive greetings for a b-side, Bob Geldof and Midge Ure had finished the final mix of Do They Know It’s Christmas at eight in the morning, following which Geldof raced over to Radio 1 to announce the imminent release of the single, announcing his intention to ensure that VAT was not levied on the fundraising profits and essentially challenging Margaret Thatcher into coming and having a go if she thought she was hard enough. That is ‘essentially’ in the sense that it was more or less exactly what he said. Inevitably, this wasn’t the last that would be heard of that particular stand-off. Braver individuals could have ventured out that evening to see Paul McCartney’s newly-released Give My Regards To Broad Street, a movie in which even less happens than does in the tie-in ZX Spectrum game that essentially just requires you to stand around at Underground stations waiting to see if any session musicians disembark, but for those who had no particular inclination to witness a four minute plus visual gag about Ringo Starr looking for a drumstick while Giant Haystacks was also somehow involved for some reason, there was always the opportunity to find out exactly what Kay Harker was up to with that leaping horse…

Despite the fact that it is not exactly entirely clear how he found himself there, Kay Harker takes up arms and assists in the battle to drive a wolf infestation from an Iron Age camp; Cole Hawlings appears after the lupine interlopers have been comprehensively routed and implies that Kay is only ‘there’ on account of his presence, which frankly only serves to make the whole matter more perplexing still. Whilst going to considerable length to emphasise that “it is Master Arnold’s box, not mine – and although I’ve called him and sought him, I’ve not found him”, he entrusts his mysterious box to Kay for safekeeping, ominously adding that “the police don’t heed the kind of wolf that’s after me”. Cautioning that its old magic is no defence against the ‘new’ magic toted by the kind of wolf that’s after him, he explains to Kay that the holder of the box can push the attached lever to the right to go small and to the left to go swift, before disappearing leaving Kay with more questions than answers; as indeed he does the viewers, who are left suitably unclear on how Kay has suddenly found himself back in his bedroom, although a less easily confused Peter famously denounces Kay’s ensuing need to get up at dawn on a freezing cold winter morning as the ‘purple pim’. Whilst trudging chirpily through what can only be described as a public transport-halting volley of snow, they witness Cole Hawlings being ‘scrobbled’ by those two dubious clergymen from Kay’s train journey, who then apparently abscond with him in a light aircraft. Kay attempts to alert the local constabulary to the hapless puppeteer’s predicament, but finds that the warning about the lack of police heedage was entirely apposite and the Inspector dismisses the entire incident as some young officers from the aerodrome having a ‘frolic’. In what they in the police apparently call a co in zidd dence, a stilted voice affecting to be Cole Hawlings calls the station to reassure them in words apparently strung together from entirely different sentences that it was indeed a prank and he is safe and everything is fine. Unconvinced, Kay opens the box and joins Herne The Hunter for a therianthropic vision quest dash through a forest, before going small and heading to The Prince Rupert’s Arms in the company of his timid associate Mouse to eavesdrop on even more dubious clergyman Abner Brown holding a meeting with his conniving informant Rat. Narrowly averting a bunch of grog-swilling ‘pirate’ rats, whose correlation or lack of to Rat is never really clarified, they witness Abner burning matches menacingly whilst outlining his plan to secure the box and exact retribution on “that interfering, overreaching boy”…

The second episode of The Box Of Delights is often remarked on as the closest that the series ever came to a ‘filler’ episode, and not without good reason. While it is certainly impressively rendered, and the blending of high quality animation and studio-based video effects – especially the opening shots which convincingly replicate the illusion of Victorian stereo photography – still looks staggeringly good even now, Kay’s nigh on five minute dart through the forest with Herne whilst assuming stag, wild duck and fish form and averting corresponding predatory woodland-dwellers really only exists as a manner of reiterating the need to exercise vigilance to Kay, something that it honestly could be argued he has something of an overabundance of to begin with. Understandably, it is a divisive inclusion, although it is worth emphasising that this episode was broadcast only days after Will, Henry and Beanpole had concluded their interminable stay at a French château learning how to press grapes in lieu of any interaction with their special effects-driven would-be cap-imposing stilty tormentors in The Tripods, and as there was doubtless a large proportion of audience crossover between the two series, viewers may well have been exasperated into hostility already. It is similarly worth emphasising just how close it is visually to a certain Paul McCartney-endorsed animation that was already starting to enjoy festive period small-screen ubiquity, and next to which it must have looked like it took itself infuriatingly seriously.

There is no disputing however that it is an extremely well done sequence that takes up barely a sixth of an episode full of extremely well done sequences, from the spurious phone call from Cole Hawlings asserting that he liked the Pie Pie so much that he has decided to stay in Shrewsbury – which employs just enough stiltedness and poorly-matched pronunciation to suggest something is afoot to the viewers too – to the thankfully off-camera wet thunks as Kay swings his sword at the rampaging wolves, to the surprisingly unostentatiously rendered flying horse itself which is remarkably convincing for something made in 1984, to an extended interlude featuring Kay and the Jones children building a snowman which really is actual filler but does not remotely feel like it. The fun, pace and drama never flag and everything that they entail is positioned perfectly. There is of course a recurrence of the central issue with The Box Of Delights in that the audience are not made even slightly aware of how and why Kay and Mouse recognise and indeed greet each other like old friends and are honestly just left to fill in the unfillable blanks themselves, but this does lead in to the staggering cliffhanger in which Robert Stephens oozes malevolence and fury without actually saying anything that would warrant such unease in the audience whatsoever, in a spectacular display of mastery of his craft that when considered rationally it is difficult to believe was inspired by what was in all honesty a relatively ordinary children’s drama serial. In a somewhat less widely noted turn, a pre-EastEnders Nick Berry played one of the pirate rats, a fact in which he always seemed to take inordinate pride whilst being interviewed to promote his accidental pop career. Will every loser win in the battle for the box, though…?

Episode Three – In Darkest Cellars Underneath (5th December 1984)

At a time when the idea of an Advent Calendar door opening to reveal even just a cursorily moulded oblong of purported chocolate still seemed like an unachievably luxurious decadence to rival Ferrero Prestige – let alone Lego, assortments of internationally sourced coffee and hot sauce and some bloke on social media unveiling twenty four imperceptibly different photos of Paul Weller on a blue background – chances are that the fifth day would prove to house nothing more exciting than a silhouette of a camel-mounted ‘wise man’ in a snowscape with a not especially star-shaped star hovering in the distance. Nonetheless, it still held an excitement in and of itself that could not be conveyed in words or indeed images – the Christmas Holidays may still have seemed almost insurmountably far off in the distance, but the nation’s schoolchildren knew that this was now unquestionably December and a momentary festive respite from the classroom was on the horizon whether those teenagers blabbering on about La Rochelle in Tricolore liked it or not. The pivotal moment that delineates Not Christmas from Christmas has been passed, and while Janet Ellis, Michael Sundin and Simon Groom are wrestling with the traditional weekly setting light to of the Blue Peter Advent Crown – albeit with something of a difference this time around, but more about that later – the Children’s BBC schedules appear to be gearing up for holiday morning levity already with the Goodie-voiced airlifted from Nutty comic animated adventures of Bananaman and a welcome repeat for Hanna Barbera’s 1978 adaptation of Godzilla, which Toho Timeline-troublingly repositioned the demonstrably grey city-smasher and his slapstick-prone nephew Godzooky as willing reptilian adjuncts to the crew of scientific research and rescue vessel The Calico, whose number incorporated thoroughly and inarguably canonical research assistant Brock Borden. Lunchtime Bertha Expanded Universe miscreant Gran, meanwhile, was apparently involved with a ‘Snowgran’ this week. We are probably better not knowing. Formerly a member of early eighties hitmakers PhD alongside Mr. Men theme tune composer Tony Hymas – no, genuinely – Jim Diamond had unseated Chaka Khan at the top of the top forty with I Should Have Known Better, a plaintive ballad that it has to be said was somewhat at odds with his visual image, which called to mind a sort of end of level boss of all of those early eighties post-punk synth wizards who looked and dressed like gang members in 2000 AD strips. By the time it hit number one, however, Jim was actively urging pop fans to buy another record instead of his. With Top Of The Pops unable to feature the song before it had charted on account of strictly enforced music industry regulations, Bob Geldof had personally phoned BBC1 Controller Michael Grade pleading for Do They Know It’s Christmas? to be permitted some pre-release exposure to the show’s enormous pop-consuming audience. In a move that was notably at odds with an unwanted and undeserved reputation he would find himself saddled with in the new year, Grade cleared a space in the schedules for the video to be broadcast immediately following Top Of The Pops with an introduction from David Bowie, sporting – as did that week’s Top Of The Pops presenters and featured acts, including one Jim Diamond – one of the very first soon to be ubiquitous ‘Feed The World’ t-shirts. Although a surprisingly little-documented earlier edit featuring significantly more Nigel Planer was also doing the rounds late in 1984, this was everyone’s first glimpse of a joyful and euphoric document of the making of a massive-selling single with the very best of intentions in a matter of hours which would later take on iconic proportions for many and varied reasons, not least the cheerfully recounted tales of how Status Quo kept everyone ‘refreshed’ during the marathon recording session. By all accounts, they would have been better advised to indulge in a ‘posset’…

Still hiding behind the skirting board watching a match=sizzling Abner Brown plotting his retribution against “that interfering overreaching boy” – whose list of transgressions apparently includes “talking on telephones” – a miniaturised Kay and Mouse eavesdrop on Rat and his somehow even shiftier if inconveniently taciturn nephew relaying information to the gang; whose ranks, to Kay’s disconcertion, are now bolstered by his old nemesis Sylvia Daisy Pouncer. With unsurprisingly little to no useful or even new intelligence forthcoming, Abner dismisses Foxy-Faced Charles and Chubby Joe with instructions to make sure that nobody is listening behind skirting boards – prompting a stifled miniature postmodern chortle from Kay and Mouse – whilst he and Sylvia Daisy dispense with the notion that Cole Hawlings could ever have entrusted his box to that “thoroughly morbid, dreamy, idle mutt” for whom she has little bar “the utmost detestation and contempt”. Instead, suspicion initially falls on the unwitting Caroline Louisa before they decide on little to no basis whatsoever that it must clearly have been delivered to the Bishop Of Tatchester and secured in a cathedral vault. Their apparent inability to formulate anything resembling a plan is then interrupted by the arrival of Maria Jones, whose combative and rebellious gangster-fixated disposition makes her in their view an invaluable potential double agent, a position that she appears to accept with a startlingly assertive dose of nonchalance and sarcasm. Understandably far from sanguine about these assorted turns of events, Kay determines to go swift back to Seekings when he and Mouse are accosted by the returning mid-revelry Pirate Rats, who they manage to avert by, well, going swift. With some understandable difficulty, Kay attempts to voice his concerns in a manner that avoids sounding like he’s lost the plot entirely to the local constabulary, with the inevitable frustrating outcome that the Inspector not only cheerfully dismisses them but is more than happy to vouch for the benevolent credentials of his Glee Club compatriot ‘The Reverend Doctor Bottledale’ and indeed his wife, chaplain and private secretary, and apparently takes no notice whatsoever of the implicit detail that Maria is technically a missing person. Deducing that Kay is “a little faint from the strain of learnin'”, he suggests that the unduly agitated youngster should partake in a ‘posset’ – served in a ‘jorum’ – which is certain to avail him of his delusions. Before Kay has the opportunity to test this unpalatable-sounding theorem, however, the local church Christmas party serves him additional cause for concern when a robbery takes place while the assembled revellers are distracted by a show from a shadowy shambling-off figure who purports to be Cole Hawlings but very evidently isn’t, and on his return home he discovers that Caroline Louisa has been lured away on a wild goose chase involving a falsified telegram alerting her to a non-existent family illness. One posset – and a nocturnal conference with some handily wolf-knowledgeable Roman centurions – later, Kay and the non-aspirant racketeer contingent of the Jones children take a wooden boat sailing when they observe Foxy-Faced Charles and Chubby Joe what?-ing away in hot pursuit. They manage to make an effective getaway by collectively going small, but suddenly realise they are hurtling towards what have now taken on the proportions of mid-stream rapids…

Just as the second episode of The Box Of Delights has become notorious for incorporating the lengthy animated interlude with Kay and Herne The Hunter adopting various animal forms in the woods to no appreciable narrative benefit, and which feels considerably more overlong than it actually is, the third has acquired a more jocular and benevolent infamy on account of the Inspector’s similarly more overlong-seeming than it actually is bewildering endorsement and description of the miraculous ‘posset’. If you believe the garrulous long-armer of the law, the constituent elements of a posset are hot milk, ‘hegg’, treacle and a grating of nutmeg, stirred up and served in a ‘jorum’, the mention of which is what finally depletes Kay’s already diminished reserves of patience. In actual historical fact – although it’s difficult to tell from all of those recipes using ‘f’s for ‘s’s, which at least suggests that the ancient Ftone Clearers might well have fuelled their activities with one – the fifteenth century concoction was originally based around a blend of heated milk and ale with a variety of spices added for ailment curing and/or to taste, which doubtless caused no little consternation to John Masefield back in 1935, although a hangover would almost certainly have momentarily availed Kay of his fanciful concerns. As bemusedly celebrated as the The Box Of Delights iteration of a posset may be, however, it is still debatable whether anyone recounting that rambunctious serving suggestion will have actually tried the frankly revolting-sounding culinary glop – but I do actually know someone who did just that, and described it with a noticeable absence of enthusiasm as “like a sort of runny liquid biscuit”. That was quite a story in and of itself, in fact, but you can find more about that here. Anyway, the point worth reiterating regarding the posset interlude is that while it might well be fondly championed for its quasi-surreal incongruity now, to anyone watching back in 1984 it would have just seemed pretty much par for the course. From Blue Peter and Why Don’t You…? to The Baker Street Boys and Puzzle Trail and probably even Jimbo And The Jet Set if you looked hard enough, Children’s BBC was routinely infused with demonstrative diversions plainly and simply outlining undemanding self-starting hobbies, activities, makes and solutions for the benefit of an audience that essentially took it as read that you had to have a touch of education with your entertainment, and while this was both lifted directly from the original novel and quite probably aesthetically inadvisable, it would honestly not have seemed especially out of place. Which is essentially saying that the Inspector was right, but it’s also worth stressing here that he, along with the overwhelming majority of the other characters, appears singularly unconcerned by the presumably trivial fact that Maria has absconded with some ne’er-do-wells and her whereabouts have been unaccounted for overnight. You do have to wonder whether he did actually add a dash of alcohol after all.

Speaking of which, Rat’s request for a drop of rum and the judiciously gobsmacked reaction it provokes is as good enough an excuse as any to mention just how fantastic Geoffrey Larder and Jonathan Stephens are as Foxy-Faced Charles and Chubby Joe. Throughout the serial they maintain a delicate balance between menace and whimsy that proves as grating as it is sinister – you really can sense Abner’s infuriation at “Charles and his infernal ‘ha ha, what?'” in this episode – and makes their eventual side-swapping drift from faintly threatening co-conspirators to realising that they are way out of their depth and the plan is hardly likely to play out in their favour all the more believable, especially when contrasted with Bill Wallis’ sneakily snivelling Rat, who really does give the impression that he is about to wander off set and stuff his face with rancid bacon rind. On a somewhat different tangent, while the church Christmas party might well involve polite games apparently based around carefully stepping back and forth to a pipe and percussion rendition of Christmas Day In The Morning, there is still a neat touch that suggests to the audience that the parcel-passing parish youngsters are perhaps not quite so historically remote from their reality after all – the enthusiastically received presents, which include such futuristic delights as The Electric Oracle, a genuine 1935 Chad Valley lightbulb-facilitated question and answer-based board game, and suggest that maybe, no matter how much the viewers at home may have been hoping for Megatron or a Keep Fit Sindy, the excitement and anticipation were still essentially exactly the same. That said, Kay and Peter seemed happy enough with a wooden boat, and although there must almost certainly have been some concerns raised about the practicality of translating it from page to screen, they really did succeed in making that ridiculous cliffhanger appear nail-bitingly hazardous…

Episode Four – The Spider In The Web (12th December 1984)

On 8th December 1984, having endured encounters with big-hatted covert enforcers, quasi-pressganged cross-channel smuggling ships, semi-feral villages full of possibly cannibalistic oddballs and an interminable stay in a chateau learning how to tend to vineyards in extreme and tedious detail, Will Parker, Henry Parker and Jean-Paul ‘Beanpole’ Deliet finally made it to the almost mythical hideout of the Freemen and immediately volunteered for a plot to infiltrate The City Of Gold And Lead in a bid to take it down from within. This was the final episode of the first series of The Tripods – a show that in several regards had a good deal in common with The Box Of Delights – and while subsequent matters would not exactly prove straightforward for the mop-haired trio and ardent followers of their exploits are still waiting for that third series, frankly that is 1985’s problem. For now, the winding up of a lengthy and hugely promoted Radio Times-hogging serial can only mean one thing – television was clearing its decks to make way for the traditional yuletide binge. As you miserably trudged through double P.E. last thing on a drizzly Wednesday afternoon it might well have felt as though school was trying its absolute hardest to keep any semblance of the most inconsequential hint of Christmas spirit at bay, but the most fundamental signs that the holidays are on their way simply cannot be suppressed. For starters even just on the BBC on the same day as episode four of The Box Of Delights, Breakfast Time had sent Glyn Christian out in ‘search’ of the traditional Christmas menu, while just about every programme from Sportsnight to Poetry 84 was soliciting votes for their traditional end-of-year mini-award ceremonies. Elsewhere in the schedules, as little as it may have had to do with Christmas, David Baxt’s reading of The Cybil War by Betsy Byars for Jackanory was setting many a lovelorn pre-adolescent heart a-flutter, illustrating only too vividly the push and pull between the traditional approach to Children’s BBC and the repositioning that loomed on the horizon. Meanwhile, with the song and the video now pretty much inescapable and nobody much objecting – apart from the government, who initially refused to declare the single exempt from the standard VAT levy; some choice words to the media from Bob Geldof saw them very quickly announce a ‘plan’ to donate the accrued revenue to Band Aid – Do They Know It’s Christmas? arrived in stock with major high street retailers on 7th December. It had, however, arrived a day late for eligibility for that week’s top forty, thereby allowing Frankie Goes To Hollywood’s Christmas song by proxy The Power Of Love a single week at the top; their otherwise engaged lead singer Holly Johnson could nonetheless be heard on the b-side of Do They Know It’s Christmas? declaiming “Feed The World, HAHAHAHAHA… I can’t get the laugh right, Bob!” down a crackly phone line. Also seeing release on 7th December were the accidentally culturally aligned cinematic pairing of Ghostbusters and Gremlins – the latter of which was frustratingly rated a ’15’ – which, in their own hugely promoted toned-down echo of the early run wild days of home video yet with something approaching a stamp of family-friendly acceptability manner, will doubtless have provided at least some of the potential audience with considerably more reason for excitement than very much sock-pulled-up posset-scoffage interspersed with archaic waffle about bacon rind tomorrow…

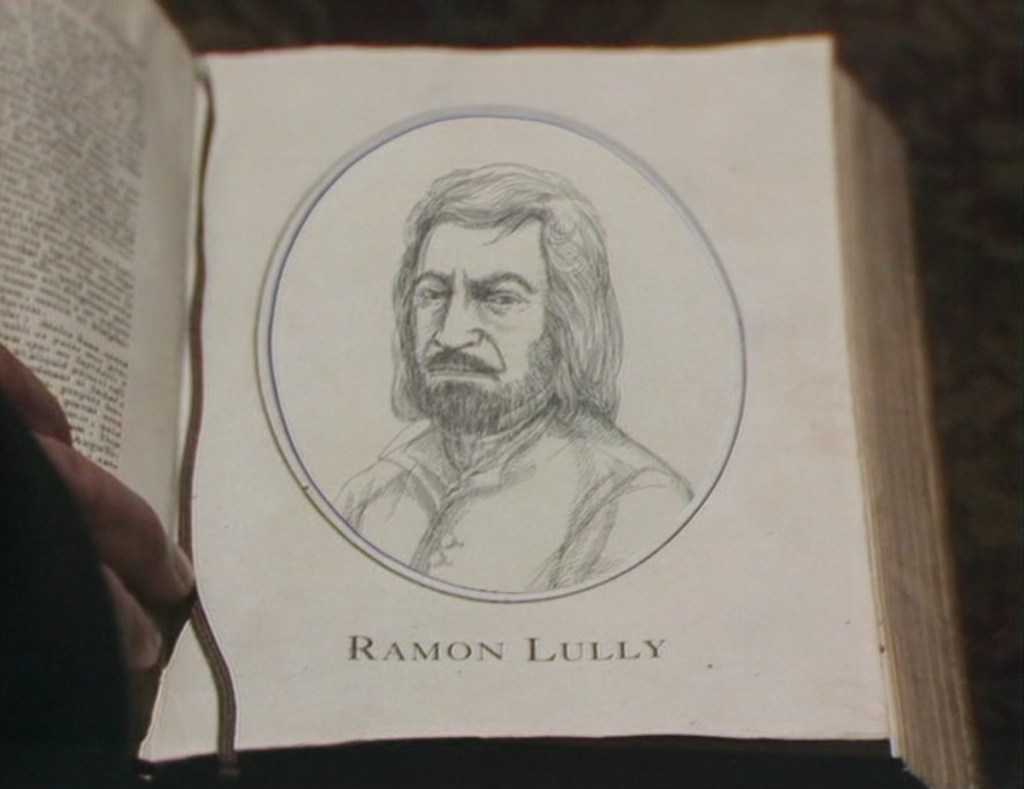

Averting the pint-sized rapids with a dash of deft wooden boat-steerage, and avoiding Foxy-Faced Charles and Chubby Joe courtesy of the by now expected going small and going swift, Kay and the Joneses return to Seekings to find that it has been comprehensively ransacked whilst Ellen was lured away by yet another phoney phone call. They have barely had time to survey the wonkily-realigned paintings when Maria returns, recounting her iron-willed encounter with the gang, with her swaggering determination even in the face of a gulp-occasioning threat by Sylvia Daisy Pouncer to feed her into the ‘Scrounger’ – from which she will apparently emerge presently as dog biscuits – having proved too much for the assorted rogues to handle. Acting on the information she was able to relate, Kay and Peter take a skyborne trip to the villains’ hideout, where they observe Abner and Charles bathing in the lake for a disconcerting amount of time before an inattentive Peter is ‘scrobbled’. With the unexplained absence of a second youngster from the same household attractingly astonishingly little concern – Kay’s attempts to alert Scotland Yard simply see him routed directly back to Tatchester police station, where the Inspector is inevitably as disinterested in doing any actual police work as ever – and a sudden outbreak of mass Bishop-scrobbling similarly failing to raise any alarm outside of newspaper headlines, Kay decides that the only thing for it is to – of course – go swift and small back to the hideout. Narrowly avoiding a collision with a yard brush, Kay observes an impatient Abner spying on his co-conspirators through a magical flip-topped desk globe and growing even more impatient still after witnessing a roast-scoffing Chubby Joe questioning the strategic wisdom of abducting masses of clergymen. Nonetheless he summons Joe for a discussion about their next move; unconvinced by a suggestion that they use ‘itching powder’ to coerce Cole Hawlings into talking, Abner shares his knowledge about thirteenth century philosopher Ramon Lully – whom Joe misidentifies as “that chap who used to do box tricks at Brixton Music Hall” – who turns out to have an improbably familiar face…

For all that the animated shapeshifting woodland constitutional and that bafflement with the ‘posset’ may have felt very much like filler, it’s actually the procession of otherwise straightforward verging on humdrum sequences in this episode that take a very long time to go more or less absolutely nowhere whatsoever that really do smack of a need to stretch events out sufficiently to justify six half hour instalments, to the extent that you find yourself wishing that they’d just bloody well hurry up and ‘scrobble’ Peter and move on to something else. Literal flights of fancy notwithstanding, this is the closest that The Box Of Delights came to the traditionally flimsy middle episodes that characterised so many other Children’s BBC drama serials at the time, even if it was still nowhere near the degree of audience patience-testing audacity of that infamous sojourn at Chateau Ricordeau in The Tripods. It’s not as if they couldn’t have made better use of that extraneous narrative space to explain, say, how Kay knew Mouse or something.

What prevents any of this from actually feeling like filler, however, is the simultaneously nightmarish and hilarious sequence in which Maria recounts her brief affiliation with the gang in a combination of flashback and narration, decorated with comically mobsterly turns of phrase and some splendidly judged overacting from Patricia Quinn, which is as good an excuse as any to mention just how good Joanna Dukes is in the role. Where the other juvenile characters, including poor old scrobbled Peter, often come across as little more than anodyne line feeds intent on reiterating the need for primness and propriety and indeed for anything and everything not to qualify as ‘the purple pim’, Maria is the ideal counterpoint to Kay. While his interactions with the adult world are founded on a not entirely unjustified if studiedly reluctant and exasperated belief that he is actually more intelligent than most of the grown-ups he is trying and failing to reason with, Maria’s are characterised by a steely self-assurance that she is as swaggering and ruthless as them and given half the chance and the appropriate armoury she would prove more than a physical match for them too. Her possibly not entirely invented tales of scholastic expulsions, wild re-enactments of the plots of movies she quite possibly has not even been allowed to actually see and barbed face-offs with the outraged and insulted Sylvia Daisy Pouncer must have felt excitingly out of place to any children reading back in 1935, and here it is one of many elements that elevated The Box Of Delights so far above so many other children’s television drama serials on either channel. Yes, technically Channel 4 was already up and running by this point, but there doesn’t seem particularly much point in drawing a direct line of comparison with S.W.A.L.K.. Joanna Dukes would go on to play sardonic but eager trainee reporter Toni ‘Tiddler’ Tildesley in Press Gang – and, incidentally, you can hear about how brilliant I thought she was in that here – and for a time was a regular sight in shows like Casualty and Rockliffe’s Folly but appears to have decided against pursuing a career as an adult actor; it seems that most of the rest of the once almost as ubiquitous younger cast of The Box Of Delights came to a similar conclusion, although notably Devin Stanfield – his imagination fired as much by the endless behind-the-scenes features on The Box Of Delights as by working on the show itself – opted for a hugely successful career in theatrical production. Meanwhile, although we are predictably provided with the inevitable lack of explanation for that video screen desktop globe whatnot, the scene that follows, with a chillingly controlling Abner outlining the sheer unfeasibly audacity of his plot to an uneasy Chubby Joe, who is very much aware that Abner knows of his privately expressed doubts but has no idea of how or to what extent he is aware of them, is brilliantly played and hints powerfully at Abner Brown’s increasing madness and delusion… or is it? Whether it is or not, it is something that we are about to see a lot more of…

Episode Five – Beware Of Yesterday (19th December 1984)

Although he would soon announce his intention to relinquish the role, the front cover of World Distributors’ The Doctor Who Annual 1984 boasted no less than two photographs of Peter Davison; captured at the TARDIS console with then-incumbent fellow travellers Tegan and Turlough, and in a sort of bendy portrait apparently making a bid to escape via the top right hand corner. Inside were the usual quotient of impenetrable text stories like The Oxaqua Incident and The Nemertines – the latter going out of its way to incorporate a half-page chemical diagram of the composition of salt – and games of ‘Monsters And Ropes’, alongside more informative features on the casting and careers of the first five actors to play The Doctor and an impressively illustrated look at how the BBC’s in-house costume designers approached working on Doctor Who. These and other similar features in the early eighties were something of a departure for the previously notoriously tenuous and tangential Doctor Who annuals, and doubtless their presence was largely at the insistence of unfairly maligned producer John Nathan Turner, who consistently pushed to some degree of resistance for higher standards of spin-off merchandise. Considering how much of the surrounding publicity revolved around behind-the-scenes features, it is fair to say that The Doctor Who Annual 1984 gives some idea of how a The Box Of Delights annual might have looked had one existed. Unfortunately, the general approach to television tie-in merchandise – and for children’s television in particular – remained what can only be described as ‘cursory’ at best, and any youngster hoping to find a television-related annual in their pillowcase in 1984 would just have to make do with Thunderbirds 2086, Magnum or Russ Abbott’s Madhouse; or indeed Bananaman, who earlier that day on BBC1 could be found in an adventure with ‘The Night Patrol’. Over on BBC2, Geraint Evans went on location in search of the origins of traditional Christmas carols in The First Noels, while Glyn Christian gave Breakfast Time an update on his search for that elusive traditional Christmas menu, and Janice Long’s Radio 1 show featured a live report from The Oblivion Boys as they visited a department store grotto, which was hopefully funnier than it sounds. This would have been the ideal moment to add a ton of The Box Of Delights merchandise to your Christmas list, but… well there wasn’t any really. There was the shoddily-covered edited-down paperback abridgement of the original novel as you can find more about here, and the theme single which again there is much more about here, but that was essentially it. Admittedly the idea of an official Chubby Joe disguise kit, a Herne The Hunter’s Overlong Colouring Book or a sort of ‘posset’-making variant of Mr. Frosty in the shape of Seekings would have been a little far-fetched, but you would have thought somebody would have seen some financial potential in at the very least a switch-incorporating replica of the box. Although perhaps it might not have been such a surefire festive must-buy after all – possibly suggesting that the general public had not actually forgotten the ‘real’ reason we celebrate Christmas after all, Do They Know It’s Christmas? by Band Aid had gone straight in at the top of the charts and had already clocked up what was fast approaching a million sales. and it is fair to say that an equally fair quantity of those copies would be given as presents on and around 25th December. With an uncomplaining Frankie Goes To Hollywood shunted down to number three, Wham!’s Last Christmas sat behind it at number two, and in an early example of the philanthropic nature that would come to characterise their later individual ideological stances, Andrew and George – who of course featured prominently on Do They Know It’s Christmas? – declared that all royalties from their single would be donated to Band Aid. Also featuring prominently on Do They Know It’s Christmas?, Sting had doubtless been expecting to be wowing cinema audiences too with his starring role in David Lynch’s adaptation of Frank Herbert’s famously dense 1965 sci-fi novel Dune, which had hit cinemas on the 14th December. Although many had high hopes for another Star Wars-level blockbuster and the movie was launched in an avalanche of action figures and sticker albums, it quickly became apparent that what anyone who had read the original book could have told you would happen had indeed happened – the director had essentially bitten off more than he could chew. We can only hope he sought solace in the latest instalment of another literary adaptation that had approached a similarly ambitious task with a more realistic awareness of its limitations…

Whilst Abner struggles to adequately convey the validity of his ambitions to poor old Chubby Joe, who assumes that the Elixir Of Life is ‘like a cough mixture’ and maintains that they should abandon their plan and cash in on the rewards offered for the captive clergy as “it’s twenty five quid even for a choirboy and we’ve scrobbled quite a lot of those”, Kay is still listening in, finding himself with a good deal of fresh information about what will be happening where and when yet no obvious route for acting on it. Staggeringly, his first thought is to try the Inspector yet again, desperately hoping to get through to him by appealing to whatever desire he may have to collar the reward money, only to be met with yet another admonishment for too much booklearning and a proffered bullseye. Reasoning that his only remaining way forward is to try reasoning with the box’s original owner Arnold Of Todi himself, Kay pays another pilgrimage to Herne The Hunter, who cautions that it is possible to send ‘a shadow of you’ into the past but infamously difficult if not impossible to return. One stylised trip through history and encounter with a stark staring mad Master Arnold – who it is safe to say is not quite the avuncular figure that Cole Hawlings’ wistful recollections have implied him to be – later, Kay narrowly effects a return to the present under threat of being lost in the even deeper past, where Abner is showing an increasingly uneasy Joe his ability to see into the future courtesy of mockingly cryptic utterances from a leafy youth he keeps ‘pegged’ under a waterfall. After abusing this privilege to ask who will win the Grand National, the impudent Joe is locked up with the clergymen whilst Abner counts his riches and inadvertently traps a miniaturised spying Kay in his treasure chest in the process – where he discovers that he has somehow lost the box. Equally inadvertent salvation comes from a Joe-rescuing Foxy-Faced Charles and Sylvia Daisy Pouncer, who have grown suspicious of Abner’s motives and plan to abscond with the loot – in a fit of conscience, Joe insists on freeing the banged-up clerics first – but whilst pocketing it unwittingly discard Kay, who finds himself further away from the errant box than ever…

It is probably fair to describe the original trailer for The Box Of Delights – and that shot of a suitably delighted Patrick Troughton extolling the virtues of the box in particular – as having been more or less inescapable in the weeks leading up to that cold winter night in November 1984. However, it wasn’t just the inter-programme continuity persistently pushing The Box Of Delights; plenty of magazine shows ran politely enthusiastic preview features as well, and when they did, they would always reach for the exact same clip – Kay ‘flying’, admittedly in an impressively rendered manner, through the pages of an assortment of illustrated history books in his bid to travel through time and locate Arnold Of Todi. Doubtless this assertion would be very heavily challenged from a present day retrospective position, but there is one harsh and inescapable detail of the decision to use this sequence to represent the entire series that cannot have escaped the attention of any of its intended audience at the time – it gave entirely the wrong idea about The Box Of Delights. Shorn of context and removed from the surreal setup with Herne ruminating on how “the past is a great book, with many pages” and the ensuing heavily stylised trip into history, it just looked like a boy in formal clothing flying through a selection of notably outdated and therefore ‘boring’ school text books, and flying with a cloyingly twee air of gleeful wonder at that. Seen in isolation, it appeared exactly as you might expect from a Children’s BBC that was still presenting the day’s schedules on a slide showing an orderly ensemble of genteel youngsters in their Sunday best wielding old-fashioned dolls and toy trains and gazing with rapt admiration at Blue Peter Flies The World well into the early eighties. Putting it bluntly, it did not exactly look like Seaview.

Thankfully, those viewers who had been won over by The Box Of Delights in spite of any understandable initial concerns that they would far rather have been watching Tucker Jenkins hightailing it from a railings-vaulting Ralph Passmore would have found themselves rewarded with an interlude so wildly off the leash in creative, visual and narrative terms whilst also battling against the by now severe budgetary limitations that if Patrick McGoohan had been tuning in, he might well have considered whether they were a bit too subtle with that business with the chimp mask after all. Finding himself on a casually realised rocky beachfront and falling afoul of some ancient Greek soldiers who appear to be at something of a tactical disadvantage when it comes to correctly identifying Trojans, and who are played with just enough of a touch of oddness and distance and indeed electronic treatment on their voices to make them feel both alien and a threat, Kay is set adrift in a boat and hurtles across animated water that frankly does not look anything remotely like water and yet somehow looks all the more like it for that precise reason. Shoring up on Arnold Of Todi’s desert island, he encounters a man driven mad by his isolation, paranoia and fear of his own creation, responding to Kay’s suggestion that he come back to the present to help to safeguard the box with a storm and lightning-heralded threat to send him back even deeper in time, with Kay barely scraping his way back to the safety of the age of The Electric Oracle and possets. The overall effect is somewhat akin to an episode of Jackanory Playhouse having a bad reaction to some cheap amphetamines and certainly the oddest interlude in The Box Of Delights by some considerable distance. It served to confirm that even this late in the series and even with the remaining budget visibly stretched, The Box Of Delights could still surprise you and indeed that judging anything on a trailer, an extract or even a still image is not always necessarily the optimal course of aesthetic action. Spanning a full ten minutes, this haphazard excursion into history does somewhat dominate the episode, but it is also worth highlighting just how affecting Chubby Joe’s gradually revealed conscience-stricken change of heart is to witness, and just how good Jason Kemp is as the inevitably never-explained Waterfall Boy, fearful of Abner but not afraid of him and slyly delighting in the fact that he is able to access information that his subjugator cannot. He is, however, sufficiently well disposed towards Joe to inform him that Kubbadar will win the Grand National by seven lengths. Unfortunately for the increasingly reluctant co-conspirator, the 1937 Grand National was in fact won by the ironically punctual Royal Mail by three lengths, and Kubbadar does not appear to have actually existed outside of John Masefield’s 1920 has-he-been-at-the-cooking-sherry horse racing dreamscape poem Right Royal. As it would turn out, however, Joe would not really need that win anyway…

Episode Six – Leave Us Not Little, Nor Yet Dark (24th December 1984)

It’s Christmas Eve. School may only have broken up less than a week ago but it already feels like ancient history, and the inevitable return in the New Year so far and distant on the horizon that you simply do not need to acknowledge it. You may well have been lucky enough to have been taken to see Ghostbusters at some point over the past week; if you were less lucky you might have been taken to see Dune, or if you were even unluckier still Catherine Mary Stewart and Lance Guest in hokey arcade game cash-in The Last Starfighter. Meanwhile, elder siblings might well have gloated about going to see the ’15’-rated Water, a misfiring satire of international administrative affairs written by Dick Clement and Ian La Frenais and starring amongst others Michael Caine and Billy Connolly; it is entirely possible that they might not have been nearly as smug on their return home. As much as anyone might now take issue with the well-intended naivety of the rush-written lyrics, Do They Know It’s Christmas? by Band Aid was into the second of a five-week run at the top and raising millions upon millions for famine relief, exactly as the entire exercise set out to do, and for many the festive season would become inextricably linked with Francis Rossi spinning round and giving a thumbs-up to the camera. Wham! are in second position with the Band Aid-fundraising Last Christmas/Everything She Wants, and just outside the top ten is Teardrops by Shakin’ Stevens, a last-minute replacement for his own ready to roll and indeed rock Christmas single which he had generously withdrawn so as not to detract from Band Aid’s potential sales. You will win no prizes for guessing what topped the festive charts the following year. If for some reason you were not particularly disposed towards giving Bob Geldof your fuckin’ money, you could always have splashed out on The Toy Dolls’ novelty punk rampage through Nellie The Elephant, Black Lace’s widely declined exhortation to Do The Conga, Nik Kershaw’s obtuse cryptic neo-sword and sorcery anthem The Riddle or Alvin Stardust’s mildly lyrically dubious I Won’t Run Away. Enjoying something of an unexpected upturn in commercial fortunes at the time, Alvin could also be found lower down the top forty with the long-forgotten So Near To Christmas and Wizzard were three places above him with a re-recorded I Wish It Could Be Christmas Everyday, while another of their erstwhile glamtastic contemporaries was enjoying significantly greater chart success with a Christmas disc that we are really best advised not mentioning now. On a less festive note, a reinvented Tears For Fears and a sparky newcomer named Madonna were quietly making their way up the top ten, Paul Young was declaring that Everything Must Change whilst effectively doing the exact opposite, and at the same time as Ray Parker Jr’s theme song from Ghostbusters was climbing back up the charts, presumably on account of being bought as a stocking filler in lieu of the unsuitably sweary novelisation and the unplayable computer game, Eurythmics were finding that they may have backed the wrong cinematic horse with Sex Crime (Nineteen Eighty Four), a song that for about two months was relentlessly sung by the ‘hard’ kids on the playground as though they were privy to some secret adult knowledge. Sometimes you do have to wonder whether anyone at all has ever actually read that bloody book before namechecking it. Whatever side of the argument about the world-feeding megastars wielding cans of Squirt in the video you may now fall on, it is still true to say that the pop charts had never known a Christmas like it and in many respects never would again; if you’re interested in some further discussion about that, incidentally, then you can find plenty of that – and indeed find out the identity of that reluctantly acknowledged now verboten Christmas hit – in an edition of Looks Unfamiliar looking at the original version of Now – The Christmas Album here.

The most interesting hit record from Foxy Faced Charles’ point of view, however, is at number three, and despite this relatively low placing it is enjoying more or less as much exposure as Do They Know It’s Christmas? itself. A song so joylessly sneered at that it is virtually impossible to find any reliable or substantial detail on its origins, Paul McCartney – in cahoots with the ‘Frog Chorus’ – had apparently originally recorded We All Stand Together at George Martin’s AIR Studios late in 1980. For spectacularly unclear reasons – even Macca himself is unhelpfully vague and waffly on the issue – this recording was shelved until an indeterminate point in 1984, when it was given further orchestral embellishments and probably a lot more additional instrumentation and vocals too but again, nobody seems to be that bothered about confirming the associated details. The reason for this reappearance was its use in Rupert And The Frog Song, an animated short in which veteran Daily Express check trouser-botherer Rupert Bear pokes his nose into what is ostensibly a ‘Frogs Only’ part of Nutwood and witnesses the amphibian choir in full Macca-miming flow. Considering that the cut-down version used as the promo video for the single opens with a live-action Paul blowing the dust off a Rupert Bear annual in an antiquated attic – there is also, it has to be pointed out, a toy Rupert in the background positioned at a crazy angle that looks unnervingly like Macca has murdered him – and is primarily composed of a lengthy plot-free assembly of various woodland animals, you could have been forgiven for thinking that the entire enterprise had been at least informed by The Box Of Delights. Of course, the dates do not quite support this supposition, but the question of what else may have inspired two remarkably similar and entirely mutually unaware projects in such close proximity is an interesting one.

Assuming that Paul McCartney had indeed been following The Box Of Delights on its original broadcast – after all, he had that operatic fish to do the promotional duties for him – then we can only hope he noticed in sufficient advance that the sixth and final episode followed a mere five days after the fifth. Shunted forward by two days so that it went out on Christmas Eve, the denouement of Kay Harker and Abner Brown’s difference of opinion about going swift and going small was immediately preceded by the final Blue Peter of 1984, which brought with it a delightfully symmetrical irony all of its own. So often reduced to chortlingly joking about having to ‘cheat’ and light the final candle on their Advent Crown early as their show did not fall on 24th December, on this occasion by an entire fluke it did. BBC1 had in fact kicked off the festivities at 6.00am with no doubt some suitably squared-off pine trees on display in Pages From Ceefax, followed by Breakfast Time getting a bit end of term with Frank Bough, Selina Scott and studio guests Keith Harris and Orville joined by Fern Britton helming a ‘Dial-A-Carol’ feature, Diana Moran offering yuletide fitness tips, Steve Blacknell opening the last door on their advent calendar, David Wheal looking ahead to festive viewing highlights – doubtless with that inescapable clip of Kay ‘flying’ through ‘history’ – and Glyn Christian advising on how to cope with Christmas lunch. It’s difficult to avoid the suspicion that we have missed something there. Later that morning Christopher Lillicrap strummed through a parable about Beefy Higgins refusing to share some figgy pudding or something in Busker’s Christmas Story, Paddington went Christmas shopping, Lassie came to the aid of ‘Manuel from Mexico’ who wanted his sick hound to recover in time for December 25th, A Charlie Brown Christmas needed neither introduction nor qualification, Cherie Lunghi read Cinderella for Jackanory, The Magic Roundabout saw Dougal writing to Santa in the hope of getting an elephant, a saxophone and a helicopter, Carol Chell and Ben Bazell enlisted the help of Bingo and the TTV gang to tell the story of Santa’s Crash-Bang Christmas on Play School, Henry’s Cat made some wry observations about Christmas Dinner, and a certain pair of brothers made their headlining television debut – albeit in big cartoony dog costumes – in The Chucklehounds Christmas. A compilation of performances from that Montreux Pop Festival thing that nobody ever quite understood and a repeat of the unseasonal Wait Till Your Father Gets Home where Harry thinks Alice’s dress is too revealing to venture outdoors in filled the gap up to the lunchtime news, followed by the first heat of Junior Kick Start, an episode of Kung Fu where Cain gets stung by a scorpion as if that didn’t happen every week, and a repeat outing for that first glimpse of those enduring Canadian cartoon irritants The Christmas Raccoons. Esteemed wartime big screen epic The Cruel Sea brought the levity down slightly before matters picked up with Noddy Holder, Toyah and Meat Loaf going head to head with Queen’s Roger Taylor, Green Gartside and Nasher from Frankie Goes To Hollywood in a battle to name three of Steely Dan’s long players in Pop Quiz Christmas Special, and a second helping of Jackanory with Jeremy Irons reading Paul Gallico’s Snowflake. Blue Peter and The Box Of Delights were then followed by a programme that we can’t really mention now, and which doubtless featured an appearance by a pop star whose 1984 Christmas hit we can’t really mention now.

Further on in the schedules came the big family movie in the form of One Of Our Dinosaurs Is Missing, which in all honesty never seemed to be off BBC1 around that time, Only Fools And Horses‘ breakthrough Christmas special Diamonds Are For Heather, a Cagney And Lacey where Mary Beth gets held hostage by a gunman – yeah ho ho bloody ho to you too – followed by the ten minute ‘Main News’ which now feels like an almost impossibly quaint reminder of a time when we were allowed to assume that nothing had happened on nominally quiet days, Val Doonican’s Very Special Christmas in which the stocking-hanging crooner was joined by Engelbert Humperdinck, Pam Ayres, The Cambridge Buskers and an assortment of BBC Weathermen badly delivering scripted puns about frost, school nativity-based comedy play Angels In The Annexe which was apparently set in the shouting ‘DON’T’ at Wade Wilson-inviting ‘Ladypool’, and a midnight-straddling mass from the Church Of St. Mary And St. John, Wolverhampton. Ladypool and Wolverhampton? There’s something in that. Meanwhile, BBC2 were always more than happy to take the low-key route on Christmas Eve, with their sole concessions to the festivities of the season being the Bing Crosby-fixated concluding part of Geraint Evans’ look at the history of the festive standard, the 1935 ‘Happy Harmonies’ short Alias Saint Nick and Aled Jones jetting over to Bethlehem to perform some carols in suitably biblical surroundings, although there’s also the final of now entirely forgotten Jerry Stevens-hosted Telly Quiz, which – one change of host, name and channel later – would return the following year as what became a longstanding much-loved festive fixture.

Over on Radio 1, Simon Bates had some special Christmas messages from ‘surprise celebrities’, Adrian John made with the festive phone-prank highlights in his Wind-Up Show, Duran Duran dropped by to discuss the records of the year with Bruno Brookes, The Oblivion Boys told Janice Long how they were preparing for ‘The Big Day’, and Adrian Juste took listeners into Christmas Day with his usual high-speed festive topical witticisms. Ray Alan and Lord Charles – who would also show up on Here’s Bob Monkhouse later that evening – took Radio 2 listeners through a selection of Prince Charles impersonations in The Impressionists At Christmas, whilst Terry Wogan, Cliff Michelmore, David Hamilton, Bill Rennels, Sing Something Simple and Music All The Way all awkwardly inserted an extraneous ‘Christmas’ into their programme billings. Radio 4 threw in odd bits of choral music and indeed lessons and carols around Ernie Wise reading Father Christmas And Pickle The Polar Bear, Helen Crayford’s rifle through her Victorian Christmas Miscellany, Alan Coren and company indulging in a spot of holly-decked ribaldry for Christmas Punch, and the tenuous presentation of Man Or Superman? under the frankly ludicrous banner Shaw At Christmas, rounding off the day’s events with a rival Midnight Mass from the Cathedral Church Of St. John The Evangelist, Salford. Somewhat conspicuously, however, in amongst their collection of Ops and RVs, Radio 3 appear to have foregone their usual Christmas Eve tradition of repeating the Pro Arte Orchestra’s 1966 reading of The Carol Symphony by Victor Hely-Hutchinson. Perhaps they had simply realised that there was just no competing with another prominent broadcast featuring it that day…

As Midnight Mass – and the opportunity to seize control of the box and its ‘old’ magic – approaches, Abner Brown is pleased to have it confirmed by his never-explained fortune telling bronze head thing that he has captured all clergymen attached to Tatchester Cathedral, but less pleased when it cautions that his obsession with doing so has afforded his opponents additional time to act against him. His response is to turn the precognitive upstart upside down – as if that actually makes any kind of practical difference – and stomp around with sufficient rage to fail to heed the cryptic suggestions that the miniaturised box is literally closer to hand than he thinks. So furiously engrossed is he in his summoning that he fails to notice a double-crossing Foxy-Faced Charles releasing all of the scrobbled clerics from the dungeon, even when he sets off to the cells on one last bid to strike a box-skewed deal with Cole Hawlings, using the Waterfall Boy’s premonition that he would have the box in his possession by midnight as a bargaining tool. Instead, his ire is only further aroused by the Waterfall Boy’s gleeful reminder that he had actually predicted that Abner would have the box under his hand rather than actually have it per se, underlining his point with a nose-thumbing “Squish to you!”. A quick burst of magic from Cole Hawlings rescues him from Abner’s vengeance and indeed his flume-bound servitude, causing the inauthentic Reverend Doctor Bottledale to absolutely blow his top and explode part of the equally inauthentic clerical training college just as Her Majesty’s finest finally show up with belated collar-feeling at last on the agenda. The ensuing structural upheaval causes flood water to course through the dungeons, but the still-miniature Kay is able to use some Hawlings-instigated pencil-hewn magic to turn a drawing of a key into an actual key and – after spotting the box glowing away in the increasingly murky depths – they are able to lead everyone to safety and onto a remarkably convenient motorboat. Meanwhile the gang are turncoatedly absconding in a light aircraft with Abner’s treasure, taking a moment to drop a bag of flour on him as they zoom overhead, and with only fifteen minutes to make it to Midnight Mass and an insurmountable snowdrift between them and the cathedral, Kay and company join hands and go swift and make it with seconds to spare. Then Kay sort of spins round and wakes up on the train and it was all a dream… or was it?

Teetering over a cliff in Turin with a coach full of stolen gold. Smacking your workplace rival in the face at your housemate’s wedding. Returning ‘home’ to find that the state surveillance you thought you had escaped is in fact still all around you. Frantically messaging Captain Marvel on a battered old pager. Forty seconds of a simultaneous discordant E Major crash on three pianos and a harmonium. Telling the audience that next week there will be “a new programme with new people”. The actual literal phrase “That’s all from This Week Next Week for this week, we’ll see you again on This Week Next Week next week, so until next week – from This Week Next Week – goodbye!”. That’s how you do an ending. Waving everything away as events that never happened, on the other hand, is lazy, insulting and indicative of a dearth of imagination and effort. From Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland and Give My Regards To Broad Street to Life On Mars and Lost to every last Supermarionation episode where Gerry and Sylvia had upped the stakes so much they couldn’t come up with a proper resolution, it is a frustrating cliché that has been responsible for some of the most disliked, divisive and just plain underwhelming endings in the entirety of narrative history. Even the at least impressively sheer audacity of Dallas using it to reverse a series of changes that had proved unpopular with viewers couldn’t escape the fundamental truth that viewers, listeners and readers are going to feel cheated by it. In fairness, it may have felt like it was somewhat less of a cliché back in 1935, but considering how much flair and spectacle and sheer invention John Masefield had shown in pretty much every aspect of The Box Of Delights up to that point, yes including the rambling about that ‘posset’, you would have thought that he would have been able to conjure up a moderately more satisfying conclusion. In the context of children’s television in 1984, however, when viewers had recently endured so many otherwise gripping serials weighed down by waffly and inconclusive endings that essentially purported that none of it had actually happened that Russell T. Davies would later state that his frustration at this was in part what drove him to become a writer himself, it is little short of inexcusable. It is the one inconvenient aspect of The Box Of Delights that nobody talking it up as the greatest television experience ever will acknowledge and will ignore completely if you acknowledge it for them. You didn’t get this with Jossy’s Giants.

What you equally did not get with Jossy’s Giants, however, was a station platform-bound Foxy-Faced Charles and Chubby Joe doffing their hats and smiling in a manner that offered the faintest of possibilities that all of this had not actually been a dream after all, and so having made this entirely reasonable objection, it is only fair to move on to a hat tip of our own. Whatever your own personal opinion of the ending might be, the concluding episode of The Box Of Delights more than delivers on tension, atmosphere and spectacle, and this is as good an opportunity as any to talk about two of the most significant contributions to the series, that have possibly conspicuously been avoided thus far on account of the fact that they really do reach their absolute highest point in this finale. The first is Robert Stephens’ portrayal of Abner Brown, which starts off exuding eerily quiet malevolence but by the end has degenerated into bellowing desperate delusional madness from a villain who knows he has lost but is incapable of accepting it, but never at any point crosses the line into either unintentional or knowing pantomime; it is a performance that slowly repositions itself from the banality of evil to the unhinged swivel-headed extremes of extremism. If anything, the comic unreality of his fellow scrobblers Geoffrey Larder, Jonathan Stephens and his real life partner Patricia Quinn only serve to underline just how threatening Abner Brown really is; they are simply unnervingly eccentric whereas he is the real irascible but softly-spoken demon-summoning deal. Citing the 1948 BBC Home Service radio production as a major influence on his own acting, and initially attempting to refuse a fee for participating in The Box Of Delights, it is difficult to avoid the suspicion that he had spent the intervening years quietly working on his own interpretation of Abner Brown and the recollections of Devin Stanfield and Renny Rye appear to suggest that one of the nation’s greatest theatrical actors simply could not believe his luck. Also in particular need of highlighting is Roger Limb’s remarkable score, which somehow manages to effectively evoke the more traditional stylings of a a modern yet remote era whilst unashamedly using modern synthesiser tones, continuing his deft reworking of The Carol Symphony for the theme music by presenting novel twists on carols and other traditional tunes to suit the darkness and lightness of tone as appropriate, and this was arguably never better realised than in the increasingly urgent yet simultaneously trepidatiously brightening suite that accompanied the frantic dash to Midnight Mass. Even given the BBC’s general ambivalence towards capitalising on The Box Of Delights in any way, it still seems staggering that it took until 2018 for the soundtrack to be released in full or indeed in basically any form whatsoever, although Mark Ayres’ outstanding mastering and arrangement of what were originally just unrelated television cues was well worth the wait; although you can find much more about that here. Included right at the end as a bonus track, however, is the full original recording of the Pro Arte Orchestra’s 1966 reading of the third movement of Victor Hely-Hutchinson’s Carol Symphony. Ironically, in the absence of Roger Limb’s embellishments, the less familiar sound of that much-loved icily twinkling introduction as it was originally recorded on a cold winter night that was so deep way back when somehow sounds more Christmassy than ever…