Even aside from the fact that they somehow always elect to employ the slightly but significantly different format of its latterday permutation Friday Night Live, there is a very good reason why the seemingly endless attempts at ‘reviving’ Channel 4’s mid-eighties late-night live comedy showcase Saturday Live never quite seem to work. This is largely down to nobody involved ever quite seeming to realise that its legendarily radical, exciting and for once genuinely ‘dangerous’ edge was very much a direct product of its time. Those crackles of lightning in the opening titles were not there for no reason, and reinventing electricity is not exactly as straightforward a task as so many appear to believe it to be.

Still barely two years old by the time that Saturday Live made its debut, Channel 4 was still very much the tabloid-baiting home of anything and everything out on a creative, cultural, social or political limb and defiantly proud of it too. On certain other channels, the late Saturday night television schedules were otherwise largely a wasteland of sporting highlights and poorly transferred oversaturated early seventies thrillers set in dingy filing rooms that even a rolled-up shirt-sleeved Robert Redford had forgotten he’d made, and even when it moved to Friday nights the show still chimed with Channel 4’s fondly-recalled tendency towards seeing the working week out with ‘alternative’ sitcoms and sketch shows and judiciously selected high quality American imports. Taking advantage of the relative lack of restrictions – although the IBA and even ‘higher ups’ at Channel 4 itself would make mid-broadcast interventions on more than one occasion – Saturday Live played with the unpredictable potential of live television in a manner that just isn’t practical now for technological reasons alone, and did so with such style and energy that it was often difficult to tell what was someone getting carried away live on air and what wasn’t. Although they were very clearly pre-planned and probably even rehearsed, it was difficult not to get swept up in the excitement when The Dangerous Brothers blew up a wall or indeed to momentarily believe that French And Saunders actually had pressed all the wrong buttons in the studio gallery. It was, as most of the regular acts were not exactly backwards in coming forwards about openly acknowledging, a highly politicised time when those with a shred of decency and humanity actually had the good sense to stand together in opposition to a common enemy, with blistering putdowns of tabloid editors and callous backbenchers who you will actually literally see on cosy early evening game shows now delivered with such force that the ‘other viewpoints’ in comedy tellingly chose to either deride the show as ‘not funny’ or even ignore it completely instead of whiningly demanding to appear on it themselves in the interests of ‘balance’. Most significantly, however, Saturday Live emerged at a time when a thriving live comedy scene was overflowing with hundreds of diverse and diverting new acts who most viewers would at that point have only known from the radio or even as just names – if indeed they knew them at all – who now all feel like they belong to an entirely different reality to the hugely promoted established performers who have dominated the various attempted revivals. Saturday Live, and the comedians who appeared on it, didn’t just reflect the moment. They felt like a sweary, audience-baiting intrusion by whatever moment was coming next. Also, there was a fairground in the studio.

Although they were rarely as well remembered as the comedians, the same was also largely true of Saturday Live and Friday Night Live‘s musical acts. Largely drawn from their own equivalent and similarly energised and indeed politicised live circuit, lower end of top forty-troublers like The Rhythm Sisters, The Proclaimers, Hipsway and Gary Howard – not to mention The Communards, who seemed to show up on a semi-regular basis and doubtless owed a good deal of their imminent chart-topping success to this exposure – very much resonated through unsuitable amplifiers with the general atmosphere and attitude of the show. The more established acts like Squeeze, Madness and The Style Council at least had a strong degree of ‘outsider’ empathy, and even the visiting blues and country artists and a then virtually unknown INXS still had at the very least the right kind of energy. There was, however, one very notable exception. Looking like a cross between a sixties movie’s pretend ‘pop combo’ made up of actors and not musicians, the ‘Beats’ from Dinky Toys’ ‘Mod Morris’ and someone who might have knocked on Hartley Hare’s door asking if he’d taken in a parcel for them, Boys Wonder took to the stage on 11th April 1987 in a whirl of polka-dot shirts and punk trousers and tore through a song that suitably namechecked both The Beatles and The Sex Pistols whilst antagonistically celebrating how much they thrived on being out of step with current trends. The studio audience were visibly not convinced, and presumably few of them would buy Shine On Me when it was released as a single a couple of months later – despite the exhortation on the fadeout to “get your friend to buy a copy!” – and no one moment better exemplifies why Boys Wonder failed to catch on with a wider audience whilst simultaneously attracting a devoted and dedicated following who in fairness probably did at least try getting their friends to buy a copy.

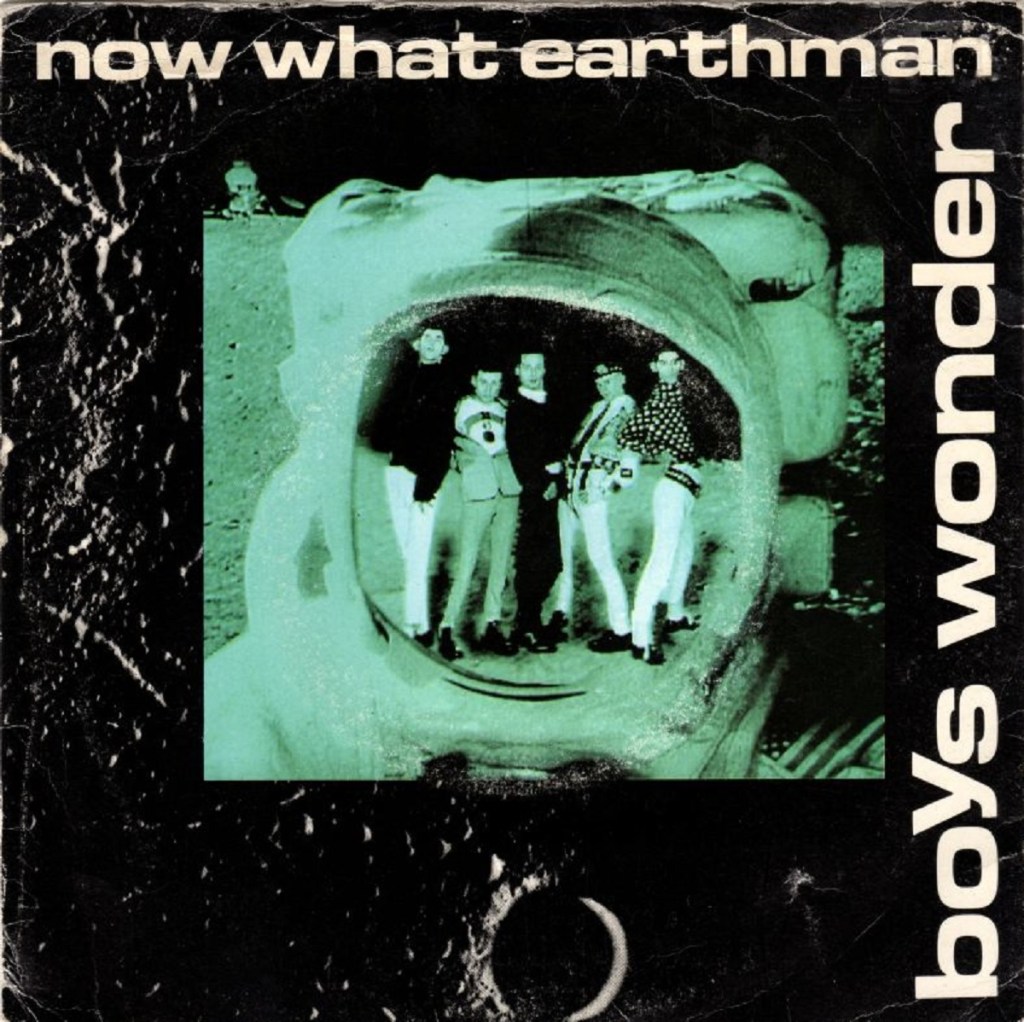

Boys Wonder – vocalist Ben Addison, guitarists Scott Addison and former Haircut One Hundred member Graham Jones, bassist Tony Barber and drummer Pascal Consoli – would only manage three singles – Now What Earthman?, Shine On Me and Goodbye Jimmy Dean, the latter a spectacular two fingers to the sniffy tastemakers who had decided that ‘style’ meant fifties Americana and fifties Americana full stop, with no room or concession for thrillingly anachronistic punky psychedelic glam pop – before they disappeared into a spiral of contractual headaches with a record label who had long since given up even trying to figure out what to do with them, and the brilliantly if parent-unnervingly riskily-titled debut album Swankers would not find itself being trepidatiously added to anyone’s Christmas list in 1987. They certainly didn’t come and go without making any noise, though. A then largely-unknown Vic Reeves was a regular presence at their phenomenally prolific live shows both on and off the stage – rumours persist that he had actually wanted to cover Dizzy with them but a misunderstanding at the record label secured the services of The Wonder Stuff instead – and a similarly taken Jonathan Ross regularly gave their singles a spin during his long forgotten stint as the host of Radio 1’s Evening Session. Even George Martin reputedly turned up to one of their gigs after a demo ‘fell’ into his hands. More importantly, whether it was the Saturday Live performance, the audaciously tongue-in-cheek Record Mirror feature capturing ‘Big Ben’ and ‘Great Scott’ at ‘home’, or a Smash Hits boxout that stood out so vividly and colourfully in a dull wash of Living In A Box and Cutting Crew and so neatly chimed with the magazine’s own sense of irreverence and offbeat humour that even ‘Bitz’ held back on the sarcasm for a moment, those scattered high profile media appearances caught and fired the imagination of a large number of devotees from way outside the London live circuit, who would then spend the next couple of decades fervently wondering what unreleased songs like Elvis ’75 and Viva Boys Wonder! actually sounded like.

As the nineties arrived, Boys Wonder’s brief and thrillingly odd moment of flying in the face of all that the eighties represented would find itself largely forgotten, and they were not even afforded any overdue recognition at the height of Britpop. There is in fact for once a positive reason that potentially explains both of the above, but we’ll be coming back to that. There has been a good deal of speculation in more recent times that Boys Wonder had simply arrived too early for Britpop, but while this is to an extent very much true, it is also not quite the full story. Way beyond the explicitly lyrically confirmed influence of The Sex Pistols and The Beatles, Boys Wonder’s music also prominently acknowledged – sometimes with direct musical quotations – some sources of inspiration that their latterday studiedly cool counterparts would never dare to incorporate, or at the very least would go out of their way to disguise any semblance of direct evidence that they had done, including The Who, Lionel Bart, Tommy Steele and The Sweet, while their self-designed combination of retro cuts and patterns and futuristic catwalk styles, which even attracted the attention of The Clothes Show, had conspicuously little in common with post-Oasis dullards slouching around in Gola sweatshirts.

Meanwhile, that elusive debut album remained just as elusive as ever. There was evidently a market for it even decades later, as confirmed by the excitement when an appearance on early ITV Nighttime show 01 For London featuring ‘new’ numbers appeared online and the fact that at one point there were five separate websites actively campaigning for its release, but successive attempts at finally getting the Swankers into the record racks came and went and the licensing issues just seemed frustratingly insurmountable. Now, however, that fervently sought-after album is finally available alongside b-sides, session outtakes and long-forgotten numbers rescued from variously archived demos as part of the anthology Question Everything, and it really isn’t difficult to see exactly what had Jonathan Ross so enthused way back when. Clearly modelled on the sort of albums that were ten a penny – and usually had a song about something being ten a penny on them too – in the days before ‘the album’ became the serious and venerated artform we are only too familiar with now, it is positively crammed with catchy hooks, imaginative arrangements, careering riffs, lyrics that tell a wryly amusing story and, doubtless thanks to their brashly shameless love of all things Tin Pan Alley, proper endings to every song, sounding not unlike what might happen if a lost Original Cast Recording of a West End musical had been invaded by a joint army of amok-running mods and Cheggers Plays Pop-friendly comedy punks.

As for all of those songs that inspired so much speculation for so long, they are possibly even better than anyone had dared to imagine. Submarine is built around an arched eyebrowedly metatextual quoting of the riff from the theme tune of Gerry and Sylvia Anderson’s sub-tastic UFO – then enjoying a repeat run on ITV – and in the anti-fashion manifesto and celebration of individualism and indeed implausible footwear that shoes Platform Boots there are very definite echoes of Vic Reeves’ early comic persona. Soho Sunday Morning takes a trip up and down Old Compton Street – “some say it’s the new King’s Road… NOT ME!” – and swaggeringly captures the hangover-flattened sensation of a birdsong-accompanied walk of shame whilst trying to work out whether your prospective paramour from the night before actually existed or not. Without becoming directly political at any point – conspicuously so, in fact, which given the general tenor of the music scene at the time suggests another possible reason why Boys Wonder were met with such indifference – Song Of Sixpence effectively contrasts the eighties veneration of financial traders and faceless office clerks with the dispiriting lot of hapless displaced manual workers. Rather than a low-key acoustic bark of finger-pointing, however, it comes framed as the sort of chirpy piccolo-paced roustabout that you might more normally have expected a beaming Max Bygraves to come out singing at the end of Sunday Night At The London Palladium. At the other end of the romantic spectrum, I’ve Never Been To Mayfair is a deliciously breezy and upbeat lament for unrequited love, wishing the unnamed hope=dashing object of affection well and tacitly accepting that it’s probably time to move on. Not so much ‘cheer up, mate, it might never happen’ as cheer up, it did happen, which is possibly an attitude that the world could do with a little more of right now, and certainly one that was – you guessed it – desperately out of step with the eighties.

If you want something of an idea of why those who discovered Boys Wonder at the time and indeed in the intervening years were so unswervingly devoted to them, though, then look no further than the splendidly titled I’m Alright Jack. In an out and out showtune built on self-consciously cheeky ‘borrows’ from Cliff Richard And The Shadows’ Bachelor Boy and David Bowie’s Love You Till Tuesday, Ben sings with undisguised glee about how much fun they are having as Boys Wonder – which, as we are reminded in a gloriously self-aware aside, he “rushed into this with my brother/we never do things by half” – and presents a pretty convincing argument that you might as well just do what excites you and see if anyone else likes it. There is none of the introspection, self-loathing or bitter recrimination that tends to characterise so many other songs about being in a band, just infectious enthusiasm and an encouragement that if they can do it, there’s no reason that you can’t too. Cheerfully dubbing themselves ‘the ones you love or hate’, Boys Wonder may not have found that the wider world was quite ready for them yet but in spite of – or perhaps in fact precisely because of – this failure to break through to the big time, they certainly did find an audience that loved them. I’m Alright Jack proudly asserts that “I don’t need the fame and fortune, I just want to entertain”, and every last note of this lost, well, wonder of an album is the work of a band who lived and breathed that very aesthetic.

It was also very clearly a value that they adhered to, as at the dawn of the nineties, Ben and Scott repositioned the collapsing and exhausted Boys Wonder as Corduroy, a band who – yet again in a fantastically sheer bloody-minded refusal to respond to what was happening around them and simply pursue what they found interesting – immersed themselves in funk-driven film soundtracks and jazz-pop crossover hits and created a sound that was closer to Sesame Street than The Good Mixer but still found themselves caught up in the excitement surrounding numerous bands who were essentially doing what they themselves had been doing years earlier. Corduroy did actually meet with a good deal of critical and commercial success and for a while this seemed to relegate the entire existence of Boys Wonder to little more than a footnote, but in time even their fans began to ask questions – or indeed question everything – about this mysterious unreleased album. Now it’s finally here – funnily enough, with the very earliest sonar traces of the Corduroy sound on Submarine – and you would be hard pushed to find a more powerfully optimistic rallying call to doing your own thing with wit, style and humour. Get your friend to buy a copy!

Boys Wonder’s former manager PTMadden got in touch after reading this to confirm that George Martin did indeed see the band play at Camden Palace after hearing a demo of I’ve Never Been To Mayfair and Shine On Me. You can find more about his fascinating career – and a book of Boys Wonder photos – at ptmadden.com.

Buy A Book!

You can find much more about the fascinating world of the pre-Britpop indie scene in Higher Than The Sun, available in paperback here or from the Kindle Store here. Get your friend to buy a copy!

Alternately, if you’re just feeling generous, you can buy me a coffee here. Get your friend to buy a… coffee?

Further Reading

This Is Television Freedom is an extract from Higher Than The Sun looking at how The KLF’s antics at the Brit Awards in 1992 literally brought the curtain down on ‘indie’ as the eighties understood it; you can find it here.

Further Listening

You can find suitably retro-tinged appearances on Looks Unfamiliar by long-time Boys Wonder fans Andy Lewis here and Paul Putner here.

© Tim Worthington.

Please don’t copy this only with more italics and exclamation marks.