Considering that just about every other prominent Victorian novelist worthy of a cloth-bound collected volume or twelve would find themselves referenced, alluded to or in some way otherwise acknowledged in Doctor Who‘s fourteenth series, it is a touch inconvenient – not least for anyone trying to find a convenient opportunity to open an unduly sarcastic overview of it with a sort of witty highbrow quip – that the production team did not extend this sudden outbreak of literary awareness to the works of one Charles John Huffam Dickens. 1977 was, after all, Doctor Who‘s own personal best of times and worst of times.

If you adhere to the epoch of belief, then this particular series of Doctor Who was marked out by the efforts of an imaginative and inventive production team with a clear creative vision that leant heavily towards classic horror and gothic fiction, a roster of ideally suited writers who were very evidently thoroughly enjoying themselves within that creative framework, and a lead actor at the height of his enthusiasm and ability accompanied by one longstanding favourite who was afforded an atypically affectionate send-off, a refreshingly different replacement whose brute force ideological and intellectual clashes with The Doctor took everything in an entirely different direction, and one whole story where The Doctor was permitted to throw himself into a surrealist kinetic art slash political conspiracy thriller entirely unaccompanied. Representing the epoch of incredulity, however, were Mary Whitehouse and The National Viewers’ And Listeners’ Association, who continued their ongoing campaign – which you can find more about the mounting momentum of here – against the more macabre turn that Doctor Who had recently taken with concurrently increasing alarm and zeal; and, to a significant extent, public sympathy. The popularity of Doctor Who itself and the popularity of the outcry against it both enjoyed – and you cannot help but suspect it was ‘enjoyed’ in both senses – such powerful prominence that matters were inevitably going to both figuratively and literally conclude with an equally surreal showdown centred around a jarringly violent setpiece, and the rights and wrongs of what happened next and indeed the rights and wrongs both of the furore over the cliffhanger to episode three of The Deadly Assassin and of anyone thinking that cliffhanger was a good idea in the first place remain a contentious issue amongst Doctor Who fans to this day.

Dispute continues to rage between those who believe that Doctor Who was never quite the same again, those who maintain that it took a much-needed step back without which it might not actually have lasted much longer, and the general public who couldn’t care less but liked it when Bellal fell through the bar or something, yet while we will have to at least address that problematic cliffhanger here along with another equally contentious issue that should possibly be left to go away of its own accord but simply will not, there are also a good deal of diversions and innovations in this particular series that are possibly more worthy or at least deserving of discussion than the pointlessly over-analysed furore that consistently overshadows them, even despite the fact that allowing it to overshadow more interesting elements is effectively giving Mary Whitehouse exactly what she wanted. For starters, there’s only a whole entire different TARDIS console room over there…

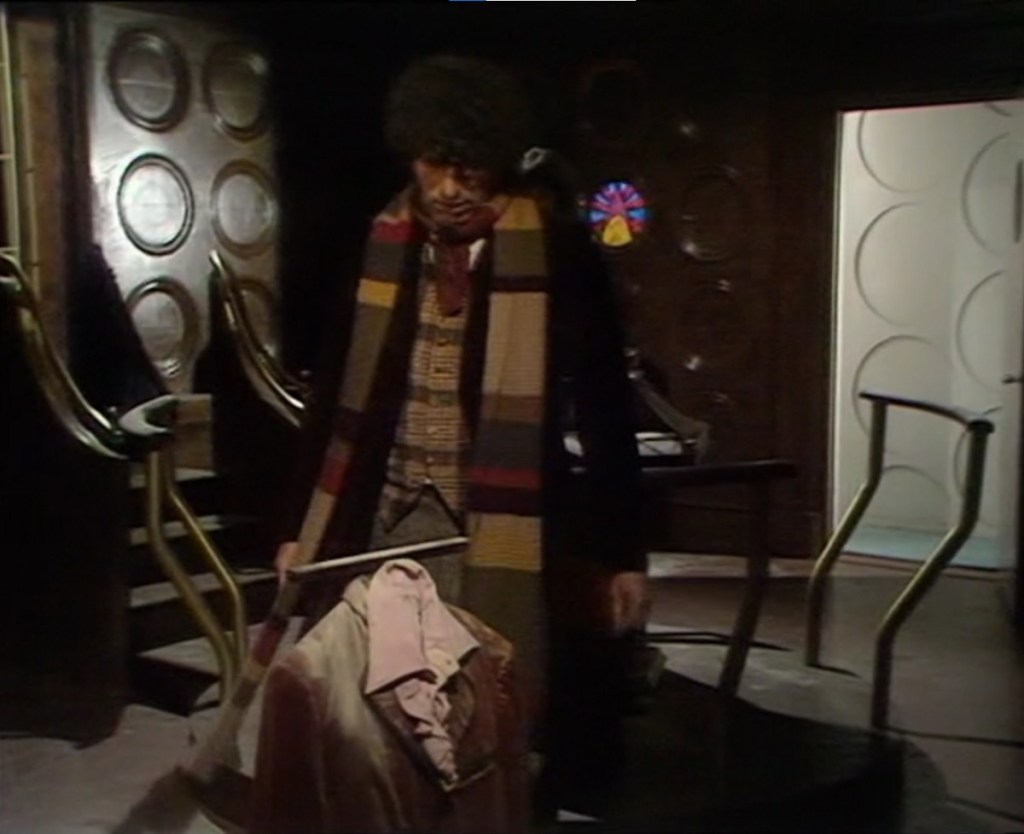

A Carved Wooden Bookend In The Shape Of A Time Rotor

Ever since Barbara had burst through those Police Box doors on the second take way back in 1963, the TARDIS Console Room set had changed surprisingly little. The huge physics homework-evoking lamp that originally hung above it had quietly vanished – so quietly, in fact, that nobody seems to be able to agree on exactly when it vanished – while the colour scheme changed from light green which apparently looked more like ‘off-white’ in black and white than ‘off-white’ did to actual ‘off-white’ itself, rare occasions saw one or more wall temporarily replaced by a massive photograph of itself due to budgetary cash-strappage, and legends are told of Jon Pertwee arranging for a bank of controls he did not much care for to be ‘accidentally’ walloped with a hammer, but otherwise it more or less adhered closely to that original long-serving design template. That was until 1976, when the production team decided to give the increasingly battered and increasingly infrequently glimpsed set a bit of a holiday and instead brought in a new ‘secondary’ Console Room that more adequately and less gleamingly reflected what everyone keeps insisting on referring to as the ‘gothic’ overtones that they had brought to proceedings. Stumbled across by The Doctor and Sarah Jane in the first episode of ‘Italianate’ – well, that’s what fanzines were required to call it by law – Fifteenth Century alien energy incursion hoo-hah The Masque Of Mandragora en route to the TARDIS boot cupboard, this supposed museum piece of space-time navigation featured dark wooden walls with neatly-arranged roundels punctuated with occasional stained glass windows surrounding what appeared to be a control-concealing writing desk with a rotating shaving mirror on top, and yet somehow managed to allow for more accurate and direct operation of the errant Type Forty than its supposedly less technologically obsolete counterpart. The overall aesthetic sat somewhere between a parish church where the lay council had voted ‘against’ to a proposal to modernise the walls, Professor Yaffle’s teetering pile of teetering piles of books and what you would probably end up with if the BBC Pinocchio was given free presentational rein for a reboot of Changing Rooms, and it not only ideally suited the Mary Whitehouse-irking new direction but also in accordance with the old adage that a change is as good as a rest brought a refreshing feel quite at odds with its stuffy and airless ambience that called to mind a decision to use the ‘other’ front room for ‘the summer’. Sadly it would not last beyond the end of this run of episodes, reputedly because as every fan reference work once had it the walls ‘warped when put into storage’ although they might not actually have done depending on who you believe, but the secondary Console Room was to have a longer term influence on those who thrilled to its varnished splintery newness; you can see it in the various suspiciously similar sets and their tendency to refresh every so often ever since Doctor Who returned in 2005. If only every ‘borrowed’ element from the mid-seventies had been rendered with as much style and imagination. Mind you, not everything within its wood-panelled walls would enjoy such enduring narrative prominence…

As If By Magic – The Mandragora Helix Appeared!

First seen in 1971, the BBC’s much-loved and much-repeated Watch With Mother show Mr. Benn related the jazz-accompanied animated adventures of a well-dressed city gent with a propensity for visiting a mysterious local costume shop run by an equally mysterious proprietor. The shop’s changing room was handily if inexplicably kitted out with an aptly named ‘Door That Could Lead To Adventure’, which would duly lead Mr. Benn into a costume-appropriate scenario calling upon him to resolve his temporary colleagues’ work and life issues with common sense and wisdom before returning home to Festive Road, invariably discovering that he had somehow retained a stray peripheral in his suit pocket which he elected to keep ‘…to help me remember’. Across thirteen instalments – and a fourteenth BBC-unnerving storybook-only one in which he donned an arrow-festooned jailbird outfit – Mr. Benn would visit the Wild West, the Middle Ages, outer space and, erm, a circus, and the costumes involved in these vignettes and more were invariably to be seen literally hanging around in the shop every week along with a handful of others that tantalisingly hinted at unseen off-screen adventures; these included a beige Napoleon ensemble, a Native American headdress and a sort of waxily plastic-looking smoking jacket accompanied by a frankly impractically frilly shirt. Quite how this would subsequently – or perhaps even technically previously – find its way into the secondary Console Room waiting to be roundly ignored by The Doctor and Sarah Jane is sadly unclear; it is entirely possible that the Third Doctor may have had some variety of encounter with The Shopkeeper – the very first episode of Mr. Benn went out two days before episode five of The Mind Of Evil after all, although he was slightly narratively inconveniently dressed as a Red Knight in that – but it has to be said that it looks more like something that one of those past incarnations of Morbius who definitely were past incarnations of Morbius no arguments might have worn, presumably after having been made to walk the yardarm by the mutinous dogs on his ship, arrrrrrrrrr, and being set ashore somewhere in the vicinity of Festive Road. Complicating matters further still, by the time of The Christmas Invasion the ensemble has apparently found its way back in to the TARDIS Wardrobe Room, hinting at an unseen occasion when The Door That Could Lead To Adventure led into one of those many corridors and Mr. Benn had a good wander around before returning home with the Stalos Gyro or something. Either way, it’s the crossover waiting to happen. Speaking of which…

If Your Sandminer Needs Infiltrating Just Call… D87!

Even despite Mary Whitehouse’s tired and tiresome difficult-second-album-esque insistence on attempting at kicking up a fuss over its purported unacceptable levels of violence and horror even after she had already got exactly what she wanted over THAT cliffhanger, futuristic almost literal whodunnit The Robots Of Death now frankly stands as proof positive that the production team were indeed using the antiquated horror and mystery overtones to their full creative advantage and not simply as a cheap and convenient route straight to headline-grabbing shocks. Confounding the imperative to feign outrage at its base unacceptability by deploying the same sort of narrative stylings and period setting as the overwhelming majority of clean-cut and thoroughly approved family-verging-on-adult dramas of the day, it relocates an Agatha Christie-informed early Twentieth Century detective thriller to a Dune-inspired ‘Sandminer’ in the far future, with retro-futuristic art deco-inflected tech designs that to all intents and purposes resemble what might happen if Reginald Jeeves was engaged to select the furnishing for a spaceship interior while Bertie Wooster was let loose on the Kenner Star Wars Droid Factory. While some of the associated costumes, props and set dressings will doubtless have been repurposed from whatever left over from some of those aforementioned similar productions was lying around in storage, other elements would almost certainly have been more or less created from scratch and accordingly then went into storage themselves; from where some of the tabards sported by Chief Mover Poul and Robophobia-debating company would find themselves reappropriated as ‘genie’ accoutrements for the panto scene in Rentasanta, the little-seen Christmas Special of Children’s BBC slapstick spooks-for-hire sitcom Rentaghost. Other than that there are occasional incongruous TWANNGGGGG sounds during clandestine cloak-and-dagger Sandminer moments that would doubtless have caused Mr. Claypole to assume that Mistress Meaker was ‘full of the joys of spring’, it is difficult to contrive any in-universe scenario in which the costumery could have travelled back to Ealing in 1978, but there’s absolutely no mistaking it. If only someone could identify the episode of Think Of A Number where Johnny Ball’s introduction to the concept of ‘the sun’ was heralded by those two sort of warbling drones from the end of the Blake’s 7 theme. Some costumes in this run of episodes, however, were somewhat less likely to find any kind of excuse for redeployment…

“It’s Not His Style At All…”

It may well have become notorious for an altogether entirely different cause of controversy, but without ever actually consciously intending to, The Deadly Assassin also posed a major mythological continuity conundrum that has puzzled scriptwriters and showrunners ever since, with their proposed solutions uniformly and proudly taking the form of unnecessarily overblown twaddle; this was the suggestion, of course, that a Time Lord is limited to thirteen regenerations and after that can no longer initiate a just about convincing dual camera mix and dissolve. While ever more convoluted reset buttony reasons have been sought to ensure that this holds absolutely no major narrative implications for The Doctor whatsoever, this suspiciously convenient good fortune was conspicuously not extended to the first Time Lord identified as having been caught out by this unfortunate limitation; The Master, whose corresponding inability to regenerate had left him with boggling eyes not entirely unlike those of a full-flight Tom Baker and the overall appearance of a Siling Haba pepper that some hipster had decided it was a good idea to ‘sear’. Admittedly this is not exactly the optimal manifestation of his or indeed her time-honoured saturnine countenance, but it would still have been entirely possible to carry this look off with something approaching style if The Master had opted to set it off against the usual black-clad garb. Instead, however, he seems to have opted for a mackintosh and matching sou’ester fashioned out of Post Office bulk delivery sacks that have been marinaded in dishwater that some coffee grounds fell into for a fortnight. Quite why this degree of accoutremental self-concealment was considered strategically necessary when he was already very successfully positioned well away from public or private scrutiny is unclear, and for once, he somehow omitted to divulge the purpose and details of this particular plan to The Doctor in a handy moment of extraneous exposition. Perhaps he had more contentious matters on his mind…

So Did Mary Whitehouse Have A Point?

In what is possibly the ultimate manifestation in both a positive and negative sense of the direction that Doctor Who pursued in the mid-seventies, The Deadly Assassin finds The Doctor summoned back to Gallifrey by an emergency notification and drawn into a conspiracy thriller surrounding a plot to assassinate The President of the High Council Of Time Lords, masterminded somewhat literally by The Master in a bid to gain access to some surplus stocks of regeneration energy and get himself out of his toasted Birdeye Chilli predicament. As the Doctor Who history books insist on telling us, The Deadly Assassin is a high watermark for the series on account of a lengthy episode-straddling extended subplot in which The Doctor is pursued in a chain of surreal vignettes through the Time Lords’ cerebral information repository The Matrix by The Master’s more straightforwardly power-hungry proxy Chancellor Goth. There are some, whoever, who would counter that it is in fact a perfectly good politically-slanted murder mystery interrupted for almost half of its total runtime by a ridiculous making-it-up-as-they-go-along parade of unconnected unimaginative jump-scares punctuated by a bank manager’s idea of ‘surrealist’ imagery and apparently filmed in that bit round the back of the supermarket, which when considered against the corresponding respective high watermarks set by everything from Gideon’s Way to Watt On Earth smacks of a quick and easy way of filling out narrative screen time with disjointed free-form rambling. During this overlong outburst of audience-bafflement The Doctor finds himself strapped to a rogue surgeon’s trolley, being laughed at by a clown in a puddle and getting his boot caught in railway points as a very small train trundled towards him helpfully sounding its warning hooter, and – at the end of Episode Three – held underwater in extreme close-up by Goth snarling “Finished, Doctor… you’re finished”. It probably goes without saying that Mary Whitehouse was on the phone within seconds, prompting a rare admission of an error of judgement from the BBC, something approaching what could possibly be considered an apology if you held it up to the light and squinted a bit and – most significantly – the final shot of Episode Three of The Deadly Assassin being physically cut from the transmission master. Although despite what fans with insatiable persecution complexes may think this was far from the only incidence of such editing under pressure in the seventies – in not altogether dissimilar circumstances the BBC would take a similarly argument-closing pair of scissors to amongst others Monty Python’s Flying Circus and I, Claudius, and even ITV were not immune to this on occasion – the fact that you could probably still count the number of significant instances on the fingers of two hands underlines just how seriously they were taking it. The furore and the ensuing physical damage to and loss of precious seconds of exceptional sacrosanct Doctor Who is often held up by fans as an outrage brought about by a confected controversy over nothing with a side order of daft old do-gooder bat trying to rob us of our good wholesome family sex and violence slurp sloo derogatory remarks about Mary Whitehouse – possibly part of the reason why some parties may be so bored of the whole matter that they deliberately used an entirely different image from The Deadly Assassin to illustrate the point – but as we have already seen here her campaigning and indeed its legacy were and indeed are more complicated than reductive reactions can possibly allow for, and on this occasion, it’s not unreasonable to say that she might actually have been in the right. The cliffhanger is an unfair and unpleasant – and, it has to be stressed, easily imitable – image to leave impressionable young viewers with, and in the eye roll-inducingly vague and formless context of what passes for a narrative in the Matrix interlude it is more or less impossible to argue that it is there for any other reason than that they felt like putting it there. Whereas you can mount a powerfully convincing defence of The Pyramids Of Mars, The Brain Of Morbius or any other story that drew her Tom Baker-tutting ire as whatever purportedly line-crossing moments they incorporated had a story-related reason to be there, in this case that just isn’t the case and any attempt to explain it away on those terms simply will not wash. Similarly, the inevitable knee-jerk fan cries of ‘but it didn’t go too far when you look at it – what about when x happened in y?’ are trying to fit an irrelevant argument onto something entirely the wrong size and shape, invariably forsaking the cold hard contextual details of the flashpoint itself to allow for a reference to a single scene in a story from decades later; even the bafflingly much-cited use of Janis Thorns a couple of weeks later represents a huge difference in and of itself as the tensions had risen to their extreme and begun – slowly – to abate by then. All in all it was an inadvisable idea inadvisably executed and it’s difficult to credit anyone involved claiming that they never expected it to escalate to the extent that it did, especially when you consider the Pythons and the I, Claudius production teams gleefully admitting that they knew they were headed for trouble but decided to risk it anyway. I still don’t think they should have edited the tape, though, but that’s another argument entirely. Well, that was all a load of fun, wasn’t it. It’s a good job we don’t have any more shocking examples of on-screen depravity and corruption to contend with.

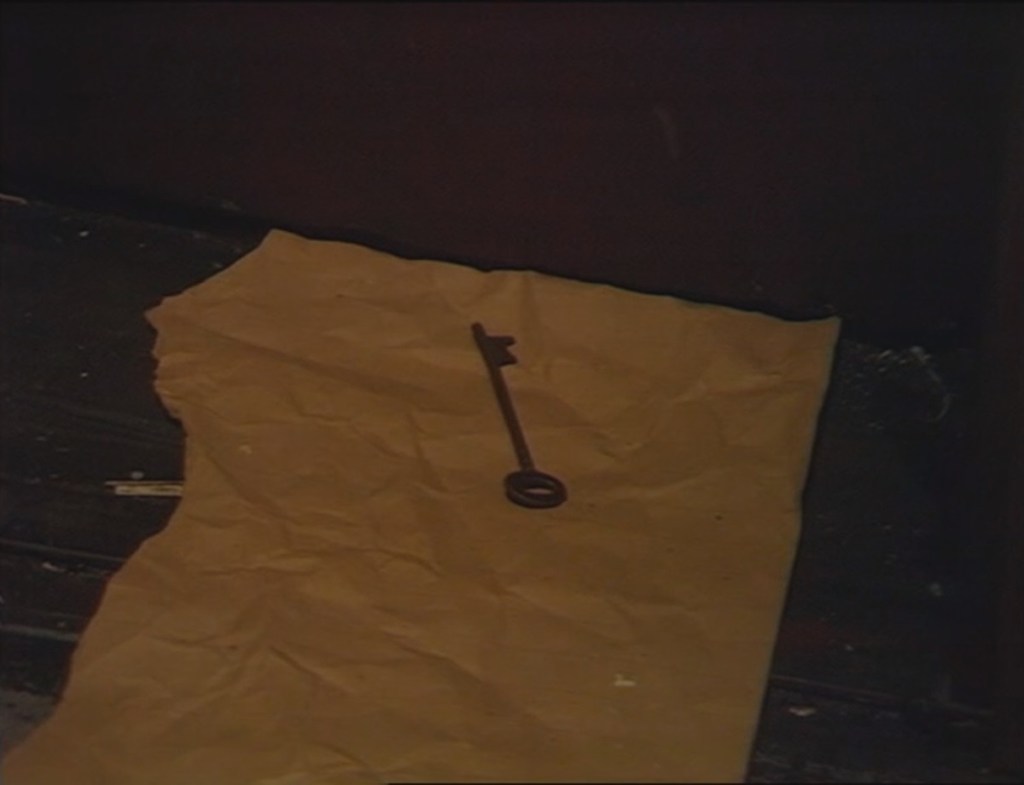

Not THAT Kind Of Key Cutting

Back when those few fractions of seconds were trimmed from the master tape of Episode Three of The Deadly Assassin, the fact that they had been shorn from the episode was more or less academic anyway; nobody really realistically expected to see it again and the thought of owning your own copy to view at your un-NVALA-troubled leisure was the stuff of a fan luminary’s wildest imaginings. By the early eighties, however, that dream was virtually a reality. Home Video was here – a new technology, a new medium, and – crucially – almost entirely unregulated. With the big studios wary of making a dent in their hugely lucrative deals to licence films for television broadcast, though, there weren’t exactly very many titles on that carousel in your local off licence to choose from, and so with nothing and nobody to stop them in came an endless parade of proudly cheap and nasty horrors primarily sourced from the USA and Italy, which were quite at odds with our national cinematic sensibilities and had either done the late-night double-bill rounds unnoticed and unwanted a couple of years earlier or else been refused a certificate for theatrical exhibition outright. Released by distributors that were essentially little more than market gap-filling startups run out of people’s utility rooms, these titles came wrapped in deliberately lurid and repulsive cover art designed to attract attention and, it could be argued, to give a false impression of the actual contents of what were often extremely ponderous efforts with long silences aimed originally at the half-watching drive-in market. With early adopters keen for new thrills that allowed them to excuse the expense of their brand spanking new home entertainment toy, the likes of SS Experiment Camp, The Driller Killer, Zombie Flesh-Eaters, Last House On The Left, I Spit On Your Grave, Cannibal Holocaust and of course The Beast In Heat quickly began to fly off the rental store shelves as a surprisingly large volume of eager and otherwise respectable viewers sought to test their endurance to both shoddily realised gore and flimsy plots and even flimsier acting, with one unamused columnist from The Times despairing after a visit to a Video Trade Fair at the proliferation of what he casually denounced as ‘Video Nasties’. This phrase quickly caught on, especially with the Daily Mail who knew a good opportunity to whip up a sales-generating moral crusade-fuelled controversy when they saw one, and what started as a fairly reasonable if possibly at least partially misguided resistance to an unfamiliar artform soon careered out of control to an extent that even the bloke in Tenebrae might have considered a bit much. Politicians and tabloids began to talk up the terrifying prospect of a nation psychologically damaged by exposure to lumbering zombies in cheap make-up, with the inevitable particular concern for the potential effects on potential children who might potentially see them under potential circumstances, and some individuals in authority who really ought to have known better began to talk about ‘Video Nasties’ as though they were some form of actual supernatural threat that could somehow ‘get’ you from beyond the tape. Inevitably Mary Whitehouse was also involved with a sustained but it should be emphasised also significantly more restrained campaign that emphasised the basic need to have some form of regulation in place above more hysterical concerns; while the utter disregard for the ability of adults to make their own minds up that this encompassed is still questionable, her statements on the matter always stressed the point that if we didn’t act now then one day we might have no control whatsoever over what was allowed to find its own way into our homes unbidden, and in retrospect it’s hard not to feel that she tried to warn us of, well, exactly where we’ve found ourselves. Although presumably she might have made an exception for unduly sarcastic ten point series by series looks back at Doctor Who. Anyway, the upshot of this was that the Video Recordings Act (1984) was drafted by politicians with little or no knowledge of the cinema industry or public tastes to replace the shambolic existing model of local police forces raiding video shops and confiscating and destroying titles that they had often arbitrarily deemed ‘obscene’ using entirely their own criteria; the confused and unclear legislation was understandably passed with little to no dissent and every title released on home video in the UK was from then on required to carry a full British Board Of Film Classification certificate. This meant that any release from what has now come to be known as the ‘pre-cert’ era could no longer be openly sold or rented, and – technically – anyone who still owns the original BBC Video release of Revenge Of The Cybermen has in their possession a videotape that is liable for forfeiture under Section 3 of the Obscene Publications Act (1964). The lack of clarity surrounding the points codified as law in the Video Recordings Act – which for one meant that nobody could work out whether The Evil Dead, despite having a full existing BBFC theatrical certificate, having been on general release in cinemas to considerable critical acclaim and having been found ‘Not Guilty’ on an obscenity charge at Snaresbrook Crown Court, could legally be awarded a corresponding certificate for home exhibition until 1990, when it was still potentially open to a fresh prosecution although none followed – almost certainly played a part in the decision to release the second BBC Video Doctor Who title, The Brain Of Morbius, in a heavily truncated form with most of the potentially troublesome imagery removed. It also helps to explain a longstanding mystery surrounding a certain title that followed in 1988; The Talons Of Weng Chiang was released essentially in its complete form apart from the removal of a brief scene at the Limehouse Laundry from Episode Five, in which The Doctor pushes a key out of a lock and pulls it back under the door on a piece of paper. This baffling edit came about as a consequence of the most troublesome clause of the Video Recordings Act, which explicitly prohibited any depictions of ‘instructional criminal behaviour’ without actually specifying what they were; this requirement was still causing home video headaches as late as 1994 over a pivotal car theft scene in the hardly aspirational Menace II Society, so the loss of a lesson in breaking and entering from Tom Baker and Louise Jameson is possibly not that difficult to understand in this context. It is also evidently somewhat more difficult to explain in anything even approaching a concise manner and it is almost as though someone not a million miles away from here may have done their dissertation on the Video Recordings Act. It might be as well to get back to talking about Doctor Who, in that case – and handily, there was someone observing that instructional criminal behaviour who is well worth talking about…

“You Try That Again And I’ll Cripple You!”

The Hand Of Fear is a likeable, imaginative and generally well-realised story with an oddly empathetic villain that, unfortunately and especially in the context of the surrounding stories in that series, features little that particularly stands out as worthy of unduly sarcastic comment other than a tediously overused ‘comedy’ observation based on a partially deliberate misunderstanding of the practicalities of accurately depicting the likely implications of a nuclear accident within the narrative confines of a family drama show with a tight production schedule. It did, however, bid farewell to Sarah Jane Smith in fine style, an occasion marked with a repressedly anguished goodbye row as The Doctor revealed that he couldn’t take her to Gallifrey, concluding on an upbeat note as she skipped off towards a new direction and new challenges before realising that he had dropped her off in entirely the wrong borough. The Face Of Evil on the other hand is a likeable, imaginative and generally well-realised story with an oddly empathetic villain that, unfortunately and especially in the context of the surrounding stories in that series, features little that particularly stands out as worthy of unduly sarcastic comment other than a tediously overused ‘comedy’ observation based on a partially deliberate misunderstanding of the practicalities of accurately depicting a huge big massive stone carving of Tom Baker’s face within the budgetary confines of a family drama show with a tight production schedule. It does, however, introduce Sarah Jane’s replacement Leela, and to say her character was something of a departure for Doctor Who would also be something of an understatement. Part of the Sevateem, a tribe of intelligent savages descended from an Earth Survey Team who crash-landed on their unnamed planet, Leela was consciously modelled on then headline-d0minating politically motivated hijacker Leila Khaled and proved a dab hand with improvised weaponry, toxin-tipped vegetation, argumentative dismissal of The Doctor’s nonsense and what effectively constituted feminism on so base and blunt a level that it might even have given Sarah Jane cause to consider investing in that pretty frock after all. A skilled hunter and proud warrior, Leela was more than capable of dealing with threats in an effective and permanent manner while The Doctor stood around prevaricating about ethical rights and wrongs, and on more than one occasion violently stood up to men attempting to intimidate her with demeaning physical and verbal overtures and implicit threats; admittedly she did so while wearing a sort of semi-skimpy outfit of animal skins supposedly designed to get ‘the dads’ watching as if they didn’t already have quick and easy access to the nearest Grattan catalogue, but even then, for once this is largely regarded as a convenient symptom of the costume design rather than the actual cause. Leela is a character who is not without her ideological complexities now, and in fairness was not without them at the time either, but overall is generally regarded as at the very least a step in the right direction with the positive aspects more than outweighing the arguably very slightly less positive ones, and it can also be stated with considerable confidence was also a character that boys could look up to every bit as much as girls did. We cannot speak for ‘the dads’ though. That said, not every aspect of this particular run of Doctor Who managed to outweigh drawbacks with advantages quite so confidently and comprehensively, and we are not even referring to THAT cliffhanger here either…

What Do We Do About The Talons Of Weng-Chiang?

The Talons Of Weng-Chiang, the concluding story of series fourteen of Doctor Who, is an ingenious, atmospheric and rip-roaringly funny Victorian detective pastiche set amidst a series of mysterious disappearances taking place around elaborately recreated Music Halls, with Tom Baker gleefully playing out his Sherlock Holmes fixation with an entire lorryload of self-awareness. It is full of sharp one-liners and visual gags, all the way from “were you trying to attract my attention”? to Leela ravenously biting into an entire joint of meat at a genteel dinner table, complete with a textbook ‘NOT ME YOU FOOL!’ during the climactic battle sequence. The making of the story was chronicled in Whose Doctor Who, a documentary in BBC2’s The Lively Arts strand that was to all intents and purposes the first ever serious study of Doctor Who‘s appeal and longevity, and effectively combines genuine scares with fantastic offbeat character work and foggy crumbling street scenes. It plays host to a remarkable scene in which Leela, captured and strapped into a life-force extraction chamber by disfigured time-travelling antagonist Magnus Greel, venomously rages that she will hunt down ‘Bent-Face’ in the great hereafter and put him through her agony a thousand times. The infamously realised Giant Rat aside, it was and remains one of the finest examples of Doctor Who that you are likely to find in any era. It also, ever so slightly inconveniently, draws inspiration from a once popular strand of pulp literary fiction involving drastically outdated ethnic stereotypes and caricatures and features a white actor in yellowface in one of the lead roles. While it may have been made entirely without malice and contains little that could even tenuously be considered directly demeaning or derogatory, let alone outright racist, it understandably drew criticism at the time and draws even more criticism now. So how do we possibly approach it? To be entirely honest, it’s an argument I would prefer to be able to leave well alone; it isn’t my fight, and not my place to take offence or otherwise, and if others whose fight it is are offended then that is possibly worth taking slightly more notice of than my enjoyment of the bit where Leela is bemused at a stuffy academic’s house not having weapons in fixed positions to guard the approaches. It would, however, be remiss of me not to acknowledge this at all if I’m finding room for complaining about the amount of bloody rope bridges in the black and white stories – not to mention the fact that I have literally built a career on finding ways of addressing problematic material from the past in the present – and ultimately it is probably better to be judged on what you actually have said than what you haven’t. So here, very reluctantly, goes. There is no point in disputing that The Talons Of Weng-Chiang looks more than a little awkward by modern standards, and that while the original intent and context should not be waved away as irrelevant, they also cannot be used as an excuse to wave away any unease at its cultural depictions now. On the other hand, it isn’t going anywhere, and as has recently been underlined by another entirely unrelated hoo-hah about an entirely unrelated story, removing it from distribution is going to draw more attention to it than not doing. It may be a mildly unwelcome reminder of changed attitudes, but you can’t do anything about the attitudes of the present by attacking those of the past, and it should be noted that those who take this to ludicrous extremes of denouncing Verity Lambert as an imperialist or Terry Nation as a eugenicist whilst adjusting their backwards baseball cap and listening to K-Tel’s Rap It Up are not really helping anyone except themselves. All things considered, then, we are lucky that the quality of The Talons Of Weng-Chiang at least partially compensates for its retrospective shortcomings and we should count ourselves fortunate that it is available in any form at all. If this availability involves appending a caption card advising of potentially insensitive content then, frankly, so be it; the supreme irony is that the only viewers who would actively complain about having to sit through two or three seconds of a mild advisory notice before a niche television programme would be the same ones who would fly into an incandescent rage and demand a refund if a Bluray release of it omitted two or three seconds of the BBC Globe in a continuity announcement. So that is me acknowleding the matter, those are my feelings on it, and if you really do feel compelled to take issue with me over it then I would politely ask you to listen to my more articulate and measured thoughts on how to address similarly sensitive material in a chat about Shang-Chi And The Legend Of The Ten Rings here before doing so. It’s a good job nobody pulls a pushed-out key under a door on a piece of paper or anything. Honestly, this bloody fourteenth series. When do we get to Ken Dodd saying “this time they’re going back to 1959 – the Rock’nRoll Years!”? To think I’d noted down that The Doctor and Sarah Jane having a bit of a chortle at the expense of ‘Italians’ with some blather about salami looked a little jarring now. Probably not a good idea to mention that little-seen BBC2 closedown on the same evening as Whose Doctor Who with a procession of blurry trodden-on photos of the likes of Vorus and Broton backed by the Radiophonic Workshop’s The World Of Doctor Who and ending with something for the ‘fellas’ – i.e. Leela – then…

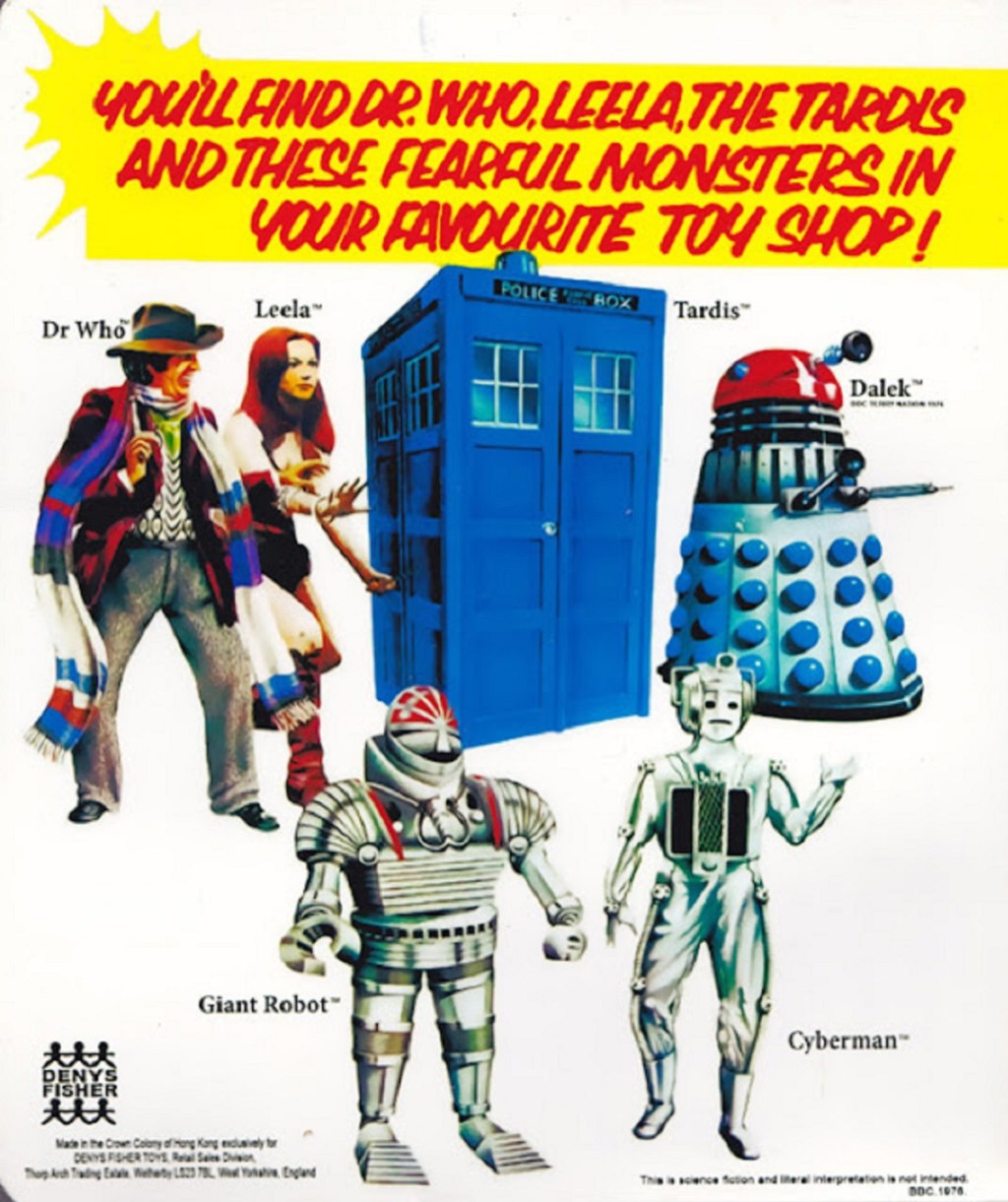

“The Fearful Inhabitants Of Outer Space!”

While we’re on the subject of pop culture ephemera from the past being judged by the standards of today, 1977 also saw the launch of Denys Fisher’s Doctor Who action figures, which no matter how much they may once have excitedly inspired a generation of youngsters to stage an ‘ice planet’ adventure by putting them in the fridge on Christmas Day are now generally regarded as little more than a punchline. The Cyberman has a nose! Leela has uncontrollable hair! The Giant Robot was in one story! The Dalek has a red dome! The TARDIS makes Doctor Who disappear and then reappear which is not how it works! The Doctor’s face was actually Patrick Mower’s face from Denys Fisher’s Celebrities Who Eat Texan Bars action figure collection or something because a seagull stole the mould except it didn’t but also it did or whatever it actually was! The K9 is… actually pretty accurate! Which is all very well and good if you are honing your irrelevant zinger that nobody needed skills for a quick witty riposte to something entirely unrelated on Gallifrey Base, but it really does do a disservice to a handful of actually pretty good action figures that are in all honesty no more or less accurate than any other tie-in range of the time but had the temerity to be created using the levels of manufacturing and brand awareness sophistication of the day – and were, much more importantly, the first real Doctor Who toys since all of those Daleks in the sixties that you pulled back and then they sort of went forwards a bit only very slightly to the left. Denys Fisher were amongst the most inventive and high quality toy manufacturers of the day – you can read about their seemingly endless range of TV and movie tie-in board games including two particularly impressive Doctor Who ones here and Mitch Benn fondly looking back at their non-branded Cyborg and Muton action figures in Looks Unfamiliar here – and irrespective of their canonical viability, their Doctor Who figures are not only more accurate than you might reasonably expect for the era but also – crucially – all that anyone actually had. Yes we all dreamed of owning Kenner Star Wars-style figures of Sentreal and General Scobie and yes Character Options would later do it all even better than anyone had ever even hoped for, but they had their point and purpose and were once widely loved and if you don’t believe that, take a look at how much a second hand boxed Leela in good condition will fetch you online. Anyway, what did taking merchandise more seriously actually get us? The Danbury Mint TARDIS? Honestly, Eldrad Must Live this all has been overly serious thus far. We could probably all do with a bit of a laugh right now…

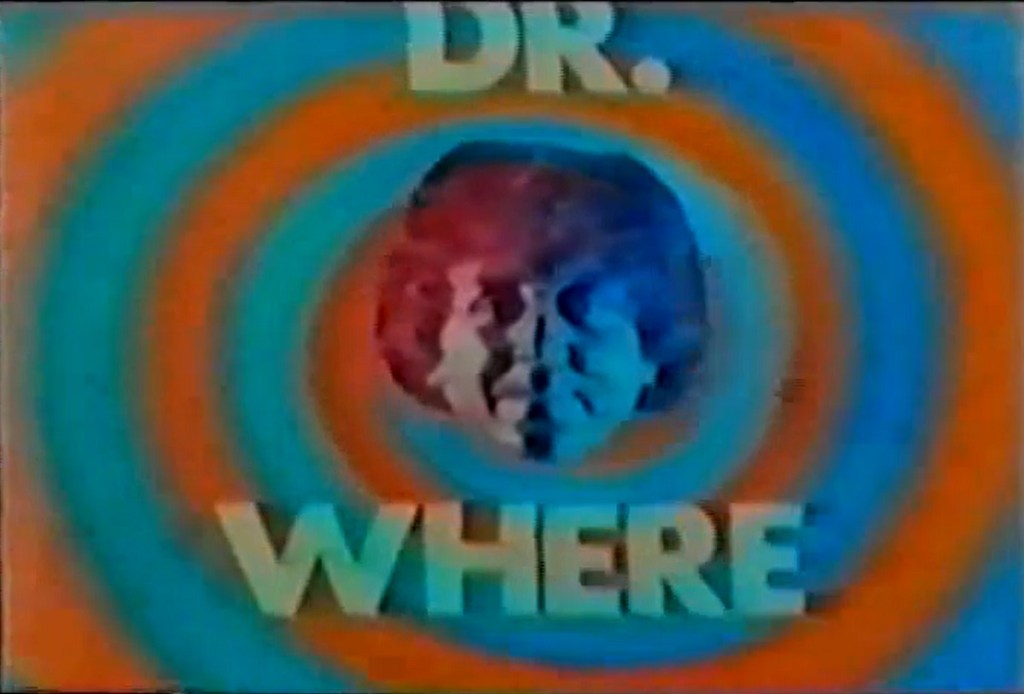

“I’m Afraid It Sounds Like Mathematics!”

Running to a single series – but repeated through to 1980 – BBC Schools series Mathshow sought to explain advanced mathematical concepts to secondary school pupils through surreal comic sketches and playlets. One of these, appearing in at least four editions in 1976, was Dr. Where, featuring Tony Hughes as a loose trigonometrically-fixated ‘PHONIS’-travelling variation on Tom Baker’s interpretation of the role complete with face-on-a-swirly-background ‘opening titles’, accompanied by Charles Collingwood as The Brigadier and Jacqueline Clarke as ‘Sally Ann’ as they sought to use long division to get them out of that week’s temporal-spatial sticky situation. Although some of the jokes would have been rejected by any halfway self-respecting Christmas Cracker manufacturer, others dryly poke fun at the structure of broadcasting and the concept of school itself, and everything is played entirely straight. It also featured sound effects from the BBC Radiophonic Workshop and the actual Doctor Who theme, so while it may not have been quite the same as getting to watch The Brain Of Morbius instead of lessons, or even quite as much like authentic free extra-curricular additional Doctor Who during classroom hours as Exploration Earth: The Time Machine (which you can find much more about here), it was still treasured by those who had the good fortune to be sat in front of the big television with shutters on it for those particular twenty minutes each week, and the fact that it is so fondly remembered by so many is hardly surprising. This wasn’t Jacqueline Clarke’s first experience of sending up The Doctor and company either – as part of the Crackerjack! (DON’T) team she had taken part in a visual gag involving the Doctor Who titles in 1974, although she had left the show – ironically to take up her Sally Ann duties – by the time of their celebrated Doctor Who sketch Hallo My Dalek! the following year. Meanwhile, just as Mary Whitehouse was getting on the blower to complain about The Deadly Assassin, Rod Hull was digging out his best seemingly endless multicoloured scarf and battered broad-brimmed felt hat as EBC1 viewers thrilled to the exploits of ‘Dr. Emu And The Deadly Dustbins’ in Emu’s Broadcasting Company. All of which collectively prove little other point than that a few people thought having a bit of a laugh with and about Doctor Who might be a bit of a wheeze but perhaps it also underlines just how popular, recognisable and indeed widely loved Doctor Who was at this point, and how much of that was down to Tom Baker specifically. Also, at the conclusion of a fairly gruelling instalment of It’s Still A Police Box, Why Hasn’t It Changed? that is liable to land me in hot water on several counts, it’s nice to be able to round matters off with a fond mention of a couple of comic actors making silly sci-fi jokes with a set square. Still, even that is essentially nothing compared to the trouble that Doctor Who itself had got into…

Anyway, join us again next time for Disco Rutans, Mike Lindup taking on The Nucleus Of The Swarm and The World’s Most Boring Swimming Pool…

Buy A Book!

You can find a much more in-depth look at the odd horror-skewed direction that children’s entertainment as a whole took in the mid-seventies in Keep Left, Swipe Right, available in paperback here or from the Kindle Store here.

Alternately, if you’re just feeling generous, you can buy me a coffee here. They probably do salami sandwiches of some form in the average high street coffee chain store, so feel free to pick one of those up too while you’re at it.

Further Reading

You can find more about Mary Whitehouse’s campaign to force Doctor Who back into line in It’s Still A Police Box, Why Hasn’t it Changed? Part Fourteen: So Come On Baby Hold Me, ‘Cause I’m The Duke Of Forgill here. There’s also more about the Denys Fisher Doctor Who board games – including the brilliant War Of The Daleks – in A Fast Exciting All-Action Game here.

Further Listening

There’s plenty of Doctor Who-related chat, including a look at numerous other tie-in toys and bizarre spin-off appearances in Schools Television, in Doctor Who And The Looks Unfamiliar here.

© Tim Worthington.

Please don’t copy this only with more italics and exclamation marks.