Once upon a time, not so long ago, the great lure and allure of charity shops, school fairs, jumble sales and even odd little boutique establishments where Victorian girls and their baggy loose at the seams cloth cats shoved ramshackle bric-a-brac into the window – as I have ruminated on at some length previously here – was that, for the curious and aesthetically open-minded, they could sometimes act as a doorway into another time, another place and even on occasion another continent. In the days before advanced technology and wider communication made it possible to connect anything and everything to a ready and willing monetised audience right down to the most mundane Corgi toy car in need of ‘some’ repainting or New English Library novel that even Richard Allen didn’t realise he’d written, one person’s discarded, dispensed with and unloved cultural ephemera was another’s exciting glimpse of a subgenre or lifestyle they knew nothing about, and so many tastes, preferences and even artistic visions were shaped by a chance discovery of a record by a singing puppet cowboy, a novel about an intelligence agent arrested with a personal stash of hashish or a book of illustrated culinary tips from the writer of Billion Dollar Brain. Sometimes – quite often, in fact – you would even stumble across something that had somehow found its way into a rack of similar items in various states of dilapidation from somewhere overseas, awash with impenetrably unintelligible language and imbued with the tantalising mystery of how and why it had not only travelled such a distance but also subsequently found itself so casually cast aside. Such discoveries were, in those long lost days, tantamount to a glimpse of an alternate universe with its own cultural history that was entirely familiar yet ever so very slightly different.

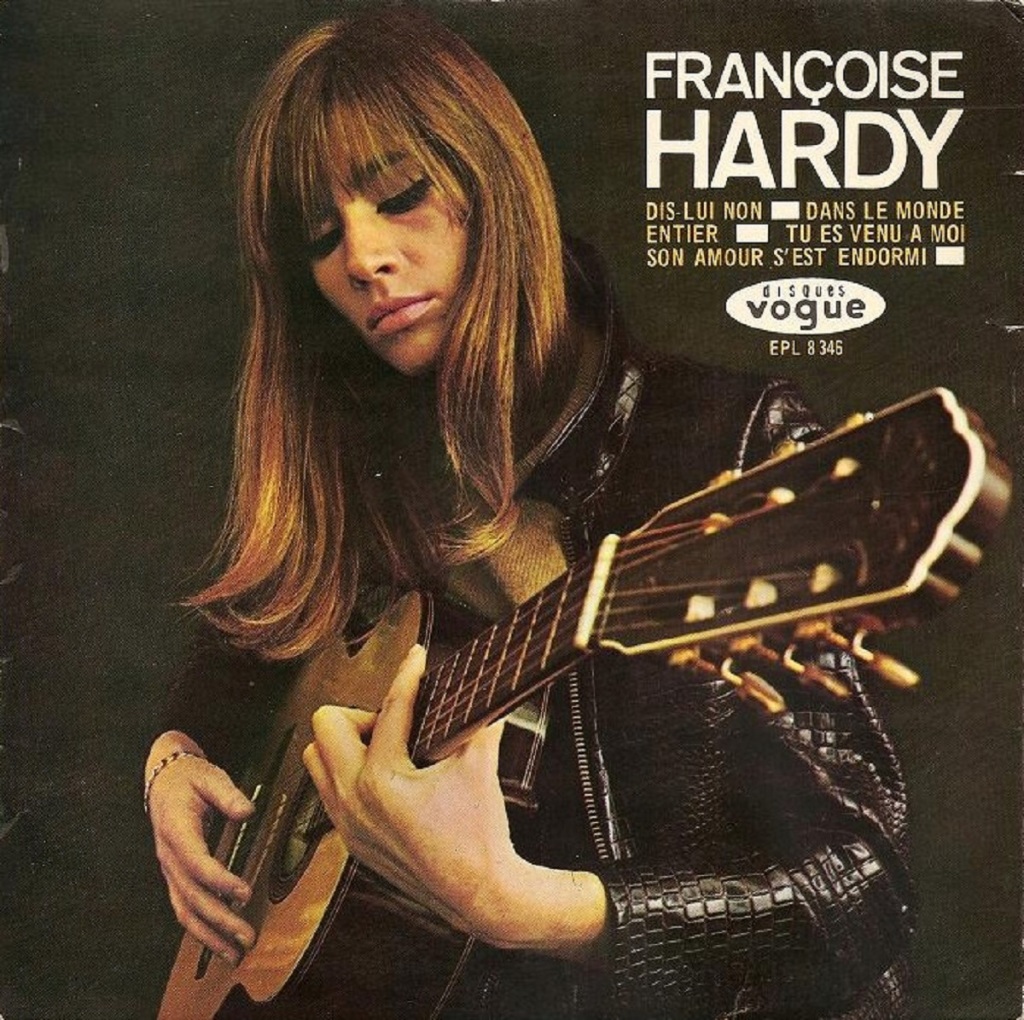

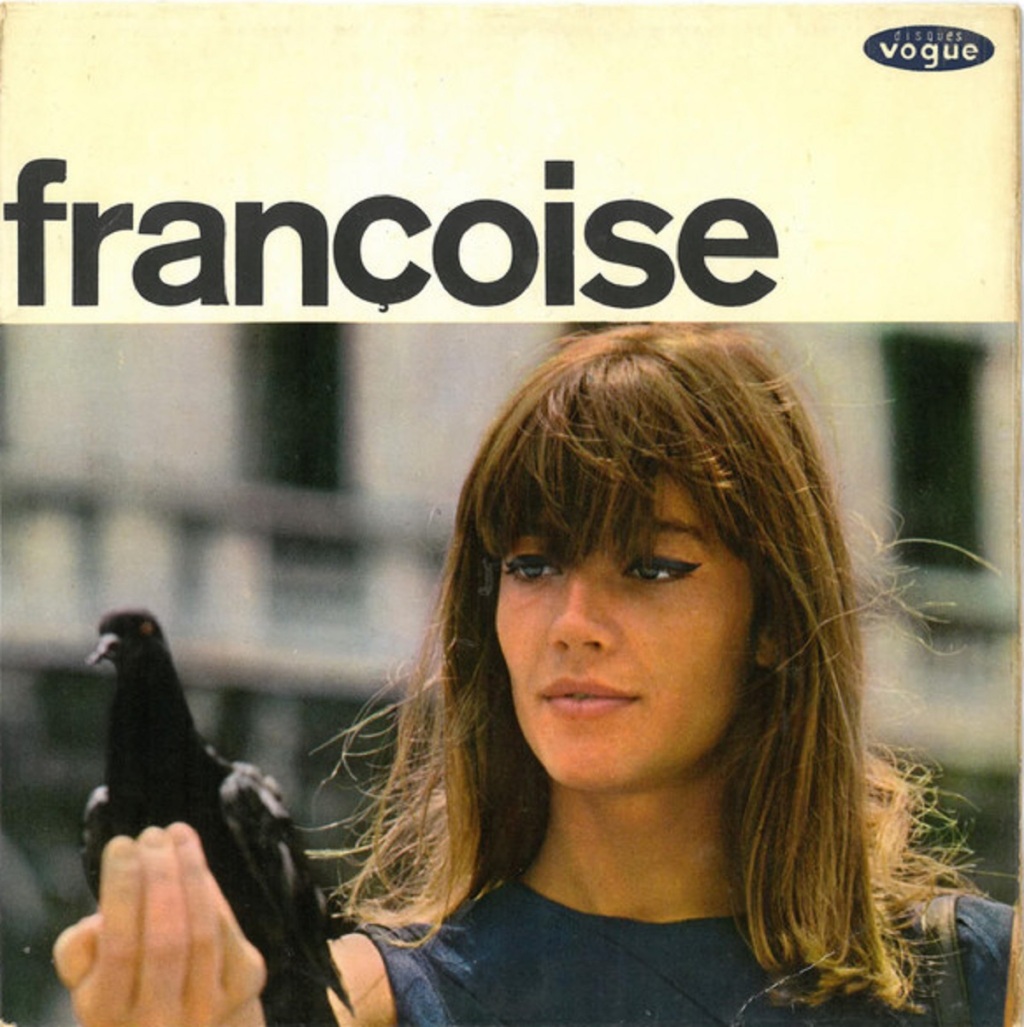

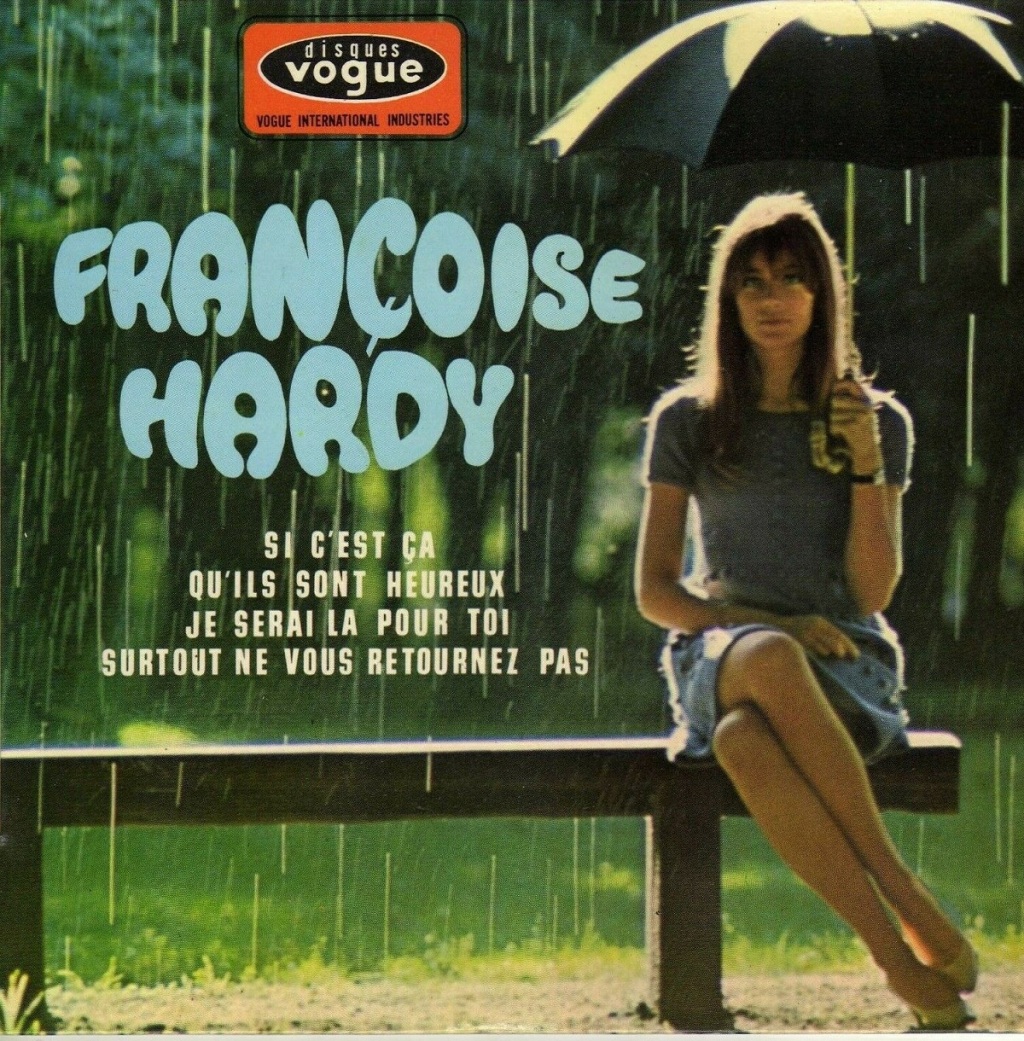

This was certainly the case when I stumbled across a 45rpm EP – again, something that appeared to enjoy much greater prominence only a short ferry trip away than it ever really did here – featuring four songs by a woman seen concentrating very hard on forming a bar chord on the cover. Françoise Hardy was one of those names that you were at least vaguely aware of in the UK – whether it was through being mentioned in The Guinness Book Of British Hit Singles and company as one of those disconcertingly ‘foreign’ types that had somehow infiltrated ‘our’ hit parade with what was invariably described as ‘the softly sung All Over The World‘, being namechecked in The Goodies’ still hilarious Charles Aznovoice, being credited as the original performer of Comment Te Dire Adieu as taken into the top twenty at the end of the eights by Jimmy Somerville And June Miles-Kingston, or being casually referenced until very recently indeed as little more than an insultingly incidental adjunct to the ‘legend’ of Nick Drake – but much like Astrud Gilberto, Serge Gainsbourg or any of those other stray continental chart-botherers, not someone you ever really heard in pretty much any circumstance. Hardly surprisingly, her records were not exactly easy to come by over here, with few sightings and far between in amongst all of the endless copies of I’ll Walk With God by Mario Lanza, and as with so many other artists just slightly to the left of The Beatles – and there were even one or two Beatles tracks you could only get hold of through this route – the scattered handful of fervent converts had to consign themselves to swapping personal discoveries with each other through the medium of compilation tapes; in fact you can find more about one particular Françoise Hardy song I first heard on a compilation tape here. Occasionally, perseverance would pay off and you might score a copy of Mon Amie Le Rose or Ma Jeunesse Fout Le Camp – on the cover of which, hilariously, her flower-chewing pose called to mind nothing more deep and existential than Ermintrude from The Magic Roundabout – but otherwise I discovered much of Françoise Hardy’s music through an odd and technologically mismatched assortment of avenues. As with so many similar obsessions, however, there was something about her music that connected with me way beyond any fervent collecting instincts, fascination with forgotten cultural artefacts, voracious appreciation for all things European and, as an unimpressed girlfriend once put it, buying any old rubbish from the sixties if it had a blonde woman on the cover. There was a reason why I fell so deeply in love with Le Temps Des Souvenirs, Voilà, Fleur De Lune, Je Ne Suis Là Pour Personne and so many others like them. Even the one about the flying horse.

The huge sweeping and lavishly orchestrated existential chanson ballads – and indeed the low-key half-murmured existential chanson ballads set against a moodily strummed acoustic guitar and little else besides – were really only part of the story; have a listen to angular art-funk rumination on emotional unavailability Le Crabe and the satirical nursery rhyme rewrite Dame Souris Trotte, both on 1970’s Soleil, if you want some idea of the scantly-acknowledged diversity of Françoise’s work. They have always been, however, the side of her music that seems to have struck a moodily strummed chord with listeners the most, and there is very good reason for this. Far from being tantrum-throwing listenability-challenging exercises in hating yourself or hating the rest of the world, Françoise’s quiet and reflective considerations on the unpredictability, volatility and sheer dice-rolling gambling with your personal happiness inextricably bound in with affairs of the heart seemed to articulate how you really thought and felt behind and beneath all of your personal form of reactive bluster. Whenever you rolled in late at night, dejected and exhausted after someone had taken five entire hours to admit that they just weren’t that into you after all, the introspective resignation to giving up on giving your heart with only the faintest yet firmest hint of a resolve to try again one day that underpinned the majority of Françoise Hardy’s albums felt as close as it was possible to get to a virtual shoulder to cry on. In short, it felt like she understood, which was more than you could say for poor old Neu!. Small wonder, then, that so many were so given to slipping on one of her long players for relief and perspective after matters did not quite go according to plan, although few can have been in the position where they proffered a hand-made CD including a Françoise Hardy song to a date who turned out not to have a CD player; if you’re interested you can find more about the time that happened to me – and it’s a lot funnier than it might sound – here. Meanwhile, on a significantly less existentially-fuelled tangent, while I have never exactly been a massive fan of those sixties stereo mixes where you get all the instruments in one speaker and the singer in the other, there are few more thrilling sounds in popular music than Francoise Hardy sighing apprehensively while she waits for her cue.

It’s more than likely that Françoise Hardy found her greatest international exposure outside of her initial flurry of sixties stardom with – and that a sizeable majority of listeners will only know her from – her mid-nineties association with Blur. Self-confessed late-night self-immersers in her music themselves, Damon, Graham, Alex and Dave had consciously modelled To The End on Françoise’s musical and lyrical style. Written and recorded in 1993 for what eventually became the Parklife album, it is perhaps the definitive encapsulation of the more open and experimental manner in which the band were thinking and approaching their music before the idea of ‘Britpop’ became defined and ossified largely as a consequence of matters outside of their control; in amongst various other more esoteric influences that would quickly become a straightforward component part of a more defined and targeted sound or in some cases dropped completely, there are pronounced stylistic echoes of a number of similar singer-songwriters in their music around this time including Nick Drake on Badhead, Syd Barrett on Miss America and Scott Walker on Young And Lovely, although they never quite seemed to find the confidence to break loose with a full-on Tim Buckley free-jazz yodel. An admirer of their music and by her own frank admission their handsome young frontman herself, Françoise eventually made contact with Blur and they went on to record La Comedie, a new version of To The End with lyrics rewritten by Françoise and more subdued orchestration bolstered by celebrated accordion player Jacques Bolognesi, which was released as a single in France and as the b-side of Country House – which of course was one of the biggest selling singles of the decade – everywhere else. Even at the time there were probably those who rolled their eyes and decried the fact that their favourite singer who only they and they alone were able to understand was being cheapened for the edification of fans of a silly little indie band playing at being pop stars with the audacity to play for audiences larger than three and a half people who looked exactly the same as them, but the fact remains that La Comedie almost certainly drew a great many listeners towards what was actually widely available at the time of Françoise’s own work – put it this way, the budget price CD compilation Les Chansons D’Amour will have started doing unexpectedly brisk business – which was almost certainly what Blur, who no doubt had their own background in swapping around Françoise Hardy tracks on compilation tapes, will have wanted. More to the point, it probably drew listeners towards her overlooked but utterly splendid 1996 album Le Danger.

The haphazardly exotic and enticingly esoteric second hand shop world that Blur and so many others like them were once immersed in and indeed emerged from may in itself now ironically be tantalisingly lost to time, but as much as the same sort of ‘aesthetes’ who once looked down on Blur and company for their Françoise Hardy fixation may ruefully bemoan its absence and blame it for whatever social and political ills are currently exercising them the most, what replaced it by default is not entirely without its advantages. The ‘lost’ worlds and hidden histories that such discoveries once hinted towards are still out there, only they’re now that much easier to find, usually only little more than a few clicks away. More importantly, Françoise Hardy is still out there and more accessible and available than ever. Hers is a voice that resonates with lost and found love, regulated and unrestrained emotion and, well, asking a mouse to wipe its feet before it comes in. It’s also a voice that is forever redolent of the soaring hope of an unexpected discovery amongst unwanted and irrelevant detritus. It’s even possible that Mario Lanza may have had a similar effect for somebody somewhere at some point. Well, possibly.

Buy A Book!

You can find more tales of adventures in and indeed discoveries from charity shop-scouring days in Keep Left, Swipe Right, available in paperback here or from the Kindle Store here.

Alternately, if you’re just feeling generous, you can buy me a coffee here. Noisette, naturellement.

Further Reading

You can find the full story of what happened when I made a CD for someone who didn’t have a CD player – including a Françoise Hardy track – in Wish I Could Sing It To You here. There’s also a tale about what happened when I found a That Was The Week That Was book in a charity shop in I’ve Heard Of Politics, But This Is Ridiculous here, and more about the making of Parklife by Blur in Lot 105 here.

Further Listening

You can have a listen to – with sleevenotes – some other songs I originally discovered through compilation tapes in Tape Over This And I Will Thump You here.

© Tim Worthington.

Please don’t copy this only with more italics and exclamation marks.