This look at how the fictional pop combo mentioned and ostensibly heard in the very first episode of Doctor Who might have fared with jive-hip beat-hungry teenagers in the real world and in an increasingly Beatlemania-skewed hit parade originally appeared in Volume Six of Vworp Vworp! – which is still available from here, and includes tons more on that very first episode of Doctor Who including interviews with Mark Gatiss and Brian Hodgson and an attempt to work out how the long-lost pre-transmission Doctor Who trailer might have looked and sounded – and I’ve reused it here as a hat-tip to Frank Ifield, who generously filled in a couple of details for one of the boxouts which I’ve also included here and seemed genuinely thrilled that he’d played even such a minor and indeed unseen part in the episode. There is something of an important point hidden away in the very fact that his photo was chosen for the girls of Coal Hill School to swoon over – even if only for a couple of years at the very start of the sixties, Frank Ifield was a huge star and for a brief but significant amount of time actually bigger than The Beatles were up to that point, yet his name is now almost entirely lost to cultural history. In theory The Beatles and indeed The Daleks should have come and gone as quickly and decisively as any other fleetingly massively popular pop group, television series, movie, book, model or anything else that rivalled their own massive popularity at the time, yet here they still are all this time later and still at Abbey Road and on BBC1 where they belong, as indeed is An Unearthly Child itself even despite attempts to literally erase it from history, firstly by whoever cleared the original transmission videotape for reuse and latterly by rights complications brought about by some form of odd deluded tantrum about ‘woke’. Yet neither happened in isolation and it could be argued that no matter how best you might think you are at being a fan of either, you cannot even really begin to understand them without considering them in their wider context; a point that I handily reflect on at some length along with diversions looking at some of the more indirect cultural references in An Unearthly Child in a longer version of Sing Along With The Common People which you can find in Keep Left, Swipe Right, available in paperback here or from the Kindle Store here. Anyway, wait in here please Susan – I won’t be long…

Although he would vehemently deny it whenever it was brought up – which was often – Decca Records’ Head of A&R Dick Rowe allegedly rejected The Beatles early in 1962 on the basis that “guitar groups are on the way out”. Eighteen months later, it was pretty much safe to say that they weren’t.

John, Paul, George and Ringo were still riding high in the hit parade with their fourth single – and fourth massive smash – She Loves You in late November 1963, with the equally chartbusting I Want To Hold Your Hand set to follow at the end of the month. Beatlemania was in full swing, but there was another hotter sensation about to burst onto the scene – and not just the mildly shirty inhabitants of the planet Skaro. The talk of the playground at Coal Hill School, John Smith And The Common Men had leapt up from number nineteen to number two with their latest beat instrumental smash, and the nation’s teenagers were pressing a transistor radio up against their ear and jiving along. There was only one minor detail standing between the popular beat combo and their dreams of Beatle and Dalek-rivalling popular culture dominance, though – they weren’t actually real.

John Smith And The Common Men made their one and only public appearance – if you could even call it that – in An Unearthly Child, the very first episode of Doctor Who, on 23rd November 1963, when their never-identifiably titled hit single is heard playing for just over fifty seconds on Susan’s radio as she waits for concerned teachers Mr. Chesterton and Miss Wright to drop by for a chat. Given that she is the ostensibly the unearthly child of the title, Susan No-Mates is generally depicted as having little in common with and indeed no discernible friendships with any of her frequently guffawing dialogue-deprived classmates, but it’s this love of pop music as well as her stylish threads and genuine distress at being yanked away from Earth in her beloved 1963 at the conclusion of the episode that cements her still widely debated teenage ambiguity. Susan may well indeed have been born in another place and another time, but she still had to be the eyes and ears of the younger viewing audience, and as most of them would have had their own eyes and ears on the ups and downs of the pop charts, it made absolute sense for her to be introduced dancing along to her current fave rave with a hand jive that is frequently described as ‘weird’ and ‘possibly alien’ despite looking more or less identical to any hand jive you would have seen in just about any pop movie or television show of the era. There is one question that never really gets asked about John Smith And The Common Men, however – well, apart from ‘what was their supposedly massive hit single actually called?’ – and it’s one that is actually quite difficult to answer from this distance. Just how accurate were they as a fictitious representation of a real-life pop sensation back when Doctor Who first started off its unique legend of timeless magic in a junkyard or whatever it is?

Although whether the same can be said of its subsequent reappearances is another question, Coal Hill School in 1963 is a surprisingly effective snapshot of a grammar school caught in a post-War cultural limbo. There are young but stuffy-before-their time teachers who probably yearn to let their hair down at the weekends – well, Barbara would probably need a scaffolding crew to get hers down – but are more than likely too restrained and refined to take any sort of hedonistic plunge. The corridors are littered with pupils in varying states of high fashion, all the way from a girl in a Breakfast At Tiffany’s-inspired Little Black Dress to a boy in what was clearly just a smaller size of whatever his father was buying. There are classrooms full of modern for the time scientific apparatus alongside dusty old text books of questionable present-day usefulness and long-term factual veracity. Like the United Kingdom in general in the long lost days of black and white television, it was very slowly trudging towards a future that was taking its merry time in getting there, and a certain quartet of caterwauling moptops would play no small part in finally bringing the two closer together. Ever since the arrival of Bill Haley And The Comets and company almost a decade earlier, however, pop music had been moving faster than the rest of society and The Beatles and company were only causing it to move faster still. Were the sounds that Susan was enthusing so wildly to Ian and Barbara about already out of date before Terry Nation had so much as got into a bit of a heated exchange with Tony Hancock?

Even aside from not knowing what their record was actually called, we learn very little about John Smith And The Common Men from An Unearthly Child itself. We hear about their remarkable chart prowess, discover that Ian is caused acute aural discomfort by fairly restrained pop music playing at a possibly even slightly less than moderate volume, and are made aware that John Smith is the stage name of The Honourable Aubrey Waites, formerly of Chris Waites And The Carollers. This in itself is a rather puzzling detail from this perspective, and one that is now difficult to place in any sort of context; although it is a fairly standard gag these days to have idle toffs trying their hand at this beat lark in anything set in the early sixties, the only real world parallels to anyone with aristocratic ancestry in the early sixties pop scene appear to have been I’m Just A Baby hitmaker – and god-daughter of Prince Phillip – Louise Cordet, and Jolly Rockin’ Weather hitmaker The Earl Of Prun, a minor royal who had turned to the latest with-it fads and trends to raise funds for his crumbling ancestral home in We Need The Money, a sketch on Peter Sellers’ 1958 album The Best Of Sellers, who wasn’t even real. Was the twisting aristocrat a common joke from the time that has somehow since become conflated with reality, and was this shared witticism even possibly what Ian’s incongruous backstory for the band was intended as? There’s no further description at all beyond any of this, but judging from their music it is probably safe to say that John Smith And The Common Men were a four-piece combo in Royal Variety Performance-friendly suits trading in the same sort of instrumental sounds that had taken The Shadows repeatedly to the top of the charts between 1960 and 1962. This was almost 1964, however, and while guitar groups were not exactly on the way out, the ones that had enjoyed success with this sort of music most certainly were. What’s more, the track that was supposedly threatening to unseat the Mersey Sound in Susan’s schooldays had actually been recorded in 1961.

Three Guitars Mood 2, as the library music track selected to represent the sound of John Smith And The Common Men is more properly if prosaically titled, was the work of a session outfit named The Arthey-Nelson Group, formed by prolific library music composers Derek Nelson and Johnny Arthey. Nelson recorded extensively for the Chappell Music Library, including many collaborations with fellow composer Roger Roger on tracks that would later find themselves being used to accompany the BBC’s Test Card broadcasts, amongst them Tele-Ski, Edelweiss Waltz and the very Hartnell era story title-like Desperate Chase. He also fronted his own skiffle outfit The Nelson Trio, mainly as a way of making a bit of extra cash on London’s thriving live circuit although they also recorded a couple of rowdy and now highly collectable singles; Roll The Carpet Up/Tear It Up for Oriole in 1957 – the same label that the infamous 1964 would-be festive smash I’m Gonna Spend My Christmas With A Dalek by The Go-Go’s would later appear on, though you can find more about that here – and All In Good Time/The Town Crier for London in 1959, with the latter’s b-side becoming an unexpected radio hit in America. More of a writer and arranger than a performer, Arthey worked extensively with many of the biggest pop acts of the sixties including Julie Rogers, Frankie Vaughan, Vince Hill, Ronnie Carroll, The Four Pennies, Cupid’s Inspiration and Barry Ryan, as well as working on slightly more esoteric fare including an album by Wendy Craig capitalising on her popularity as the star of BBC1 sitcom Not In Front Of The Children, and Vince Hill’s theme from Mickey Dunne, a post-Alfie BBC1 lad-about-London comedy drama starring Dinsdale Landen, which it’s fair to say Mary Whitehouse was not exactly an avid fan of. Along with the more upbeat party-friendly Three Guitars Mood 1 and its total lack of any obvious resemblance whatsoever to Tequila by The Champs, Three Guitars Mood 2 was commissioned for a 10″ library record published by the Conroy label in 1961, and was effectively recorded to order as off-the-shelf facsimile ‘pop’ music. As the duo pocketed their session fees, they probably only ever envisaged a couple of seconds of one track being used in the background while a twist-attempting Lance Percival fell over in front of a vicar in a coffee bar in a comedy movie called something like What A Knees-Down!. Instead, almost entirely by accident, it ended up becoming arguably their most widely known and loved work by some considerable distance. If there is one detail of that first episode that Doctor Who fans will mention over and above any other, it’s ‘that music’.

So we are already dealing with a piece of music that was a fairly cynical imitation of the top pop sounds of over two years previously, and if we assume that An Unearthly Child takes place in the week prior to 23rd November 1963 – it is set on a school day, after all – then the top forty singles chart for that week looks like a decidedly unhospitable atmosphere for poor old John Smith And The Common Men, and they wouldn’t have any Thals to help them become acclimatised to it either. If there is one unavoidable fact that the hit parade for that week makes all too abundantly clear, it’s that Merseybeat and its associated geographical variants were here to stay. Gerry And The Pacemakers were enjoying a third week at the top with You’ll Never Walk Alone, with The Beatles sat behind them at number two with She Loves You, and The Searchers making it a Liverpudlian triumvirate with Sugar And Spice at number three. Billy J. Kramer And The Dakotas were also in the top ten – at nine – with I’ll Keep You Satisfied, while The Fourmost were at number twenty three with the Lennon/McCartney-penned Hello Little Girl and The Merseybeats were closing in at number thirty six with It’s Love That Really Counts. Manchester was exercising the traditional local rivalry with You Were Made For Me by Freddie And The Dreamers at number eleven and The Hollies with Searchin’ at number thirty three, while Dagenham’s own Brian Poole And The Tremeloes were eagerly getting in on the act with Do You Love Me? at number twelve.

Slightly less adjacent to The Cavern both geographically and sonically, Phil Spector’s Wall Of Sound was proving a sturdy barrier to hapless Aubrey Waites with The Ronettes’ Be My Baby at number four and The Crystals’ Then He Kissed Me at number fourteen, while The Dave Clark Five wasted everyone’s time as always with their number thirty eight smash Glad All Over. Meanwhile, just sneaking in at number thirty two, a raucous r’n’b outfit swaggering out of The London School Of Economics were making a lot of noise over a lot of noise with I Wanna Be Your Man; The Rolling Stones were here, and would very quickly prove a more serious challenge to The Mersey Sound than a dated number that even a fairly square teacher got a little fed up with could really have hoped to be. John Smith And The Common Men did have some friends in that week’s top forty, including The Shadows at number thirty with Shindig, Cliff Richard at number five with Don’t Talk To Him and Jet Harris And Tony Meehan at number forty with Applejack, while Chuck Berry’s 1959 hit Memphis Tennessee was the unlikely occupant of the number ten slot, having been reissued to counter a cover by the definitely no relation Dave Berry And The Cruisers, which was by then struggling to climb higher than number twenty eight. None of these pop veterans were exactly dominating the charts or the airwaves, though, and with the rest of the top forty made up of folk, showtunes and full on movie-era Elvis Presley, it’s difficult to see any situation in which that polite toe-tapper would have vaulted up seventeen places so effortlessly. In fact the highest climber that week was You Were Made For Me, which could only manage a comparatively pathetic leap of a mere eleven places, and the previous week’s number nineteen, Miss You by Jimmy Young, had impressively achieved the exact opposite and gone down one place.

So, while John Smith And The Common Men have their place in Doctor Who history – as part of an episode, we should not forget, that there wouldn’t have been any other episodes without – it’s doubtful they would have fared too well in the harsh reality of the real world pop business. This is probably the point at which a million Doctor Who fans will leap in with theories about how this proves that Susan was indeed even more ‘unearthly’ than we thought and that the track had been deliberately chosen to enhance her mystique as a girl out of time who was only posing as a teenager in pre-Swinging London and couldn’t even quite get that right and something something timeless magic, but the reality is almost certainly that it sounded enough like current pop music to a director in his mid-twenties – which, it should not be overlooked, would have seemed ‘past it’ to teenagers in 1963 – and was easily licensable enough to make a dramatic – if not dramatic per se – point. It did, however, make an unlikely if hardly ‘unearthly’ favourite out of a library track that otherwise might never really have been heard by anyone – come on, how many of you have actually heard Three Guitars Mood 1? – and from this distance, well, it’s difficult for us to really tell the difference anyway. A fleeting cameo appearance by The Beatles aside, this would be more or less Doctor Who‘s last direct brush with the hit parade until The War Machines brought everything back down to Earth three whole years later. A lot had changed by then, but they did at least manage to get the music in London’s hippest hotspot more or less spot on. Although that said, there was a distinct lack of actual ‘mods’ in the capital’s most happening mod hangout…

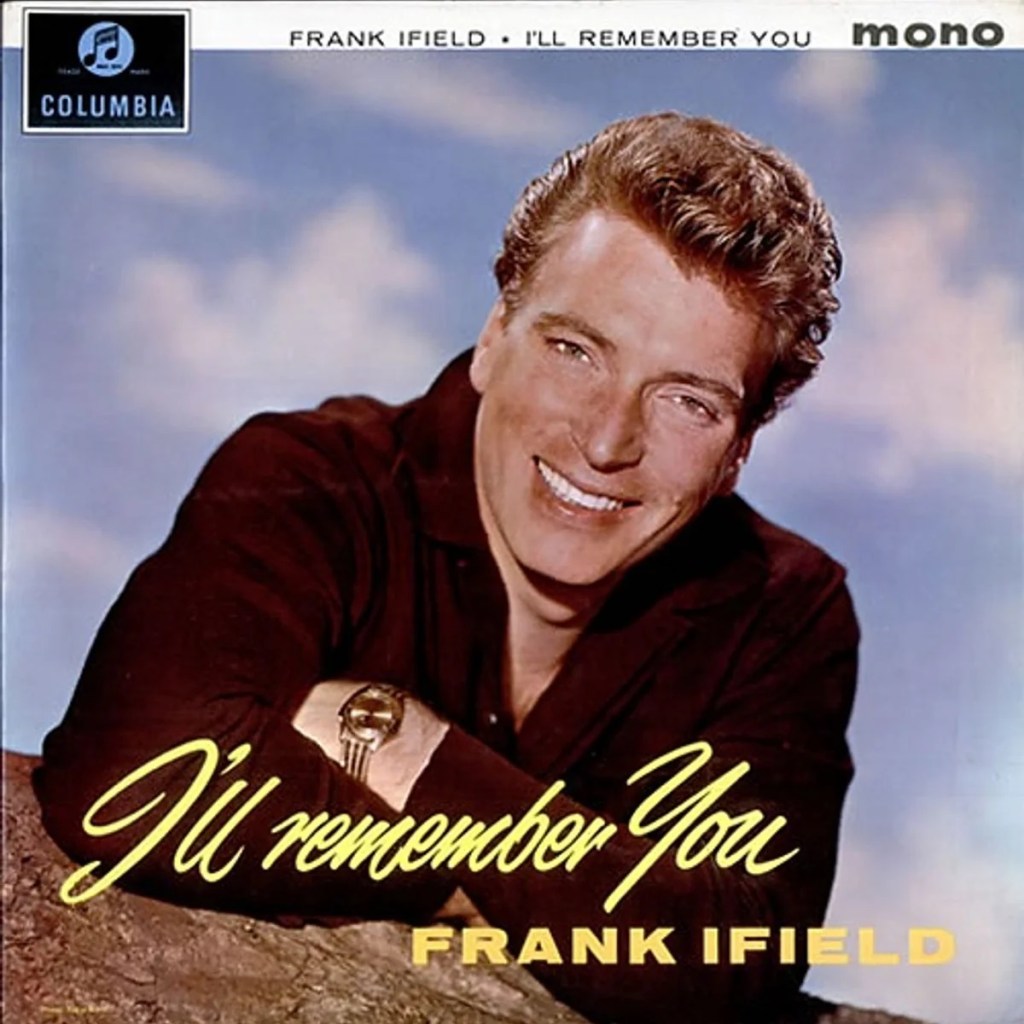

Doctor Who began with the not exactly epochal or indeed timeless or magical opening line “wait in here please, Susan – I won’t be long”, but while Susan did indeed wait in there with her dial tuned to whatever radio station was blasting out John Smith And The Common Men, certain of her classmates out in the corridor were pledging their pop allegiance in an altogether different direction. Very much in the foreground while that inaugural non-conversation is taking place, a rather glam girl and her slightly more dowdy mate are busily conferring over a pin-up in a magazine when a class clown-type boy comes along and pulls an exaggerated Kenneth Williams face while exclaiming “ooooooh yes!”, causing them to share a delicious-looking private joke about him. The barely visible object of their affection? Real life chart sensation Frank Ifield.

Looking not unlike the puppet ‘pop stars’ that would turn up in many a Gerry and Sylvia Anderson series, squarer-than-square-jawed Frank Ifield had a massive hit in 1962 with the mid-paced ballad I Remember You, which topped the UK charts for seven weeks – and, in an early example of public exasperation at pop songs outstaying their welcome, drove The Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah band to incorporate it into their live set as the significantly more Frankenstein-themed I Dismember You. His astute fusion of deep fried country and rock’n’roll balladeering was clearly what the public wanted, however, as the livelier double a-side Lovesick Blues/She Taught Me How To Yodel and the cinematic The Wayward Wind both also went to number one later that year. The syrupy Nobody’s Darlin’ But Mine stalled at number four early in 1963, but shortly afterwards Confessin’ (That I Love You) went all the way to the top again. Whacked full of whipcrack effects, a deliberately harder cover of Mule Train could only climb as high as number twenty two – in the week of John Smith And The Common Men’s massive chart leap it fell to number thirty seven – and despite Don’t Blame Me making the top ten in 1964, that was pretty much it for the man with the ooooooh-occasioning quiff as a chart contender. Until 1990, when he found himself back in the top forty with a rave-styled reworking of She Taught Me How To Yodel. No, really. While it’s possible that Susan’s classmates would have been yanking on Global Hypercolour t-shirts and getting bleep rush to the sounds of Sueno Latino and Guru Josh if they had been stalking the corridors twenty-odd years later, back in 1963 they were doubtless feeling pangs of lovelorn adolescent loyalty as the guy on their bedroom walls started to fall from chart favour. The Kenneth Williams-evoking joker, on the other hand, had evidently been listening to Radio Luxembourg and knew full well that Frank Ifield was old hat, daddio, and was more than certain of exactly what was what when it came to the exciting new sounds emerging from the Mersey region. Yes, that’s right. Ian And The Zodiacs.

Buy A Book!

You can find an expanded version of Sing Along With The Common People, delving even deeper into the now almost impenetrably remote cultural backdrop to An Unearthly Child, in Keep Left, Swipe Right, available in paperback here or from the Kindle Store here.

Alternately, if you’re just feeling generous, you can buy me a coffee here. Watch out for a careering Lance Percival though.

Further Reading

There’s a lot more about that very first series of Doctor Who – and not all of it entirely reverential towards that ‘timeless magic’ – in It’s Still A Police Box, Why Hasn’t It Changed? Part One: Breakin’ Down The Walls Of Hartnell here.

Further Listening

There’s more TARDIS-centric chat about everything from the ‘Talking Book’ of Doctor Who – State Of Decay to Barry Letts’ version of Pinocchio in Doctor Who And The Looks Unfamiliar here.

© Tim Worthington.

Please don’t copy this only with more italics and exclamation marks.