No matter how many increasingly spuriously-numbered anniversaries you might throw at them, as far as the wider viewing audience are concerned Doctor Who began on 28th December 1974. That was the moment when Tom Baker was effectively first seen in the role, and the moment that the popular ‘image’ of Doctor Who that persists to this day was instantly cemented in all of its jelly baby-proffering ubiquity. Even now, and even after almost a dozen further lead actors in the title role – one of whom wasn’t even a man – the immediate default image that most members of the general public will call to mind whenever Doctor Who is mentioned, even if the mention comes courtesy of a moving digital advert in an Underground station with its backwards baseball cap on admonishing the non-WAP Enabled squares who aren’t hip to the streaming jive, daddio, is of a man in what is apparently officially and irrevocably known as an ‘intergalactic’ scarf. All of that fanfare over The Three Doctors barely eighteen months previously and all of a sudden they may as well never have existed, with the first decade of Doctor Who‘s history relegated to incorrect lists of ‘The Doctors’ in the wrong order from olders and wisers (“I should know, I used to watch it!”) whose opinion you had neither solicited nor valued. Solicitor Grey, The Old Silurian, The Morok Messenger and Warrien belonged to the past; welcome to a staring-eyed battered felt-hatted permanent present.

In fairness, Tom Baker was quite unlike William Hartnell, Patrick Troughton and Jon Pertwee in almost every manner imaginable; a relative newcomer and virtual unknown, an acclaimed heavyweight actor who had dazzled critics in a procession of forceful interpretations of decidedly family-unfriendly roles, and so dedicated to his craft that at the time he was cast in Doctor Who, he was working on a building site in preference to accepting parts he did not find interesting. In marked contrast to the publicity-shy Troughton and Hartnell’s fixation with being perceived as a ‘legitimate’ actor, he not only threw himself into a phenomenal amount of in-character promotional appearances with abandon, but also went to great lengths to ensure he was also recognisably behaving in a manner befitting ‘The Doctor’ when out and about and off duty in case he was spotted by an impressionable child. His immersion in a role that he entirely made his own was so total and absolute that it was difficult not to view anything else he appeared in, whether it was Call My Bluff or Frankenstein: The True Story, as somehow constituting ‘extra’ Doctor Who.

This was not solely down to the remarkable personability that Tom Baker brought to the role, however; Barry Letts and Terrance Dicks had recently handed production duties over to Philip Hinchcliffe and Robert Holmes, who envisaged a somewhat darker and literary horror-influenced direction for Doctor Who in line with a peculiar general trend towards a more macabre tone in children’s entertainment at the time, which incidentally you can find some more thoughts about here. It’s true to say that this realignment had effectively started with Letts and Dicks during Jon Pertwee’s final series – and you can find more about that here – and that the most significant entry in the new series, if not the most celebrated Doctor Who story of all time, came about as a direct consequence of Dicks suggesting that Terry Nation might like to ‘show us where The Daleks came from’. The fact fully remains, though, that with the perfect lead actor, the perfect production team and at the perfect time – this was where and when the perception of the series as a Basil Brush and Bruce Forsyth-sandwiched big-hitting emblem of the glory days of BBC1 owning Saturday Night television really began – Doctor Who was suddenly to all intents and purposes an entirely new show again, just as it had been in what must equally suddenly have surely felt a lot longer ago than 1970. Adding to all of this, the series was – virtually without precedent – underpinned by a loose rough running storyline of sorts, though they had to draw a line under a handful of remnants from the previous Doctor first…

Filmed In RobotVisionTM

In keeping with the approach adopted by the series as a whole, Robot picked up directly from where Planet Of The Spiders had left off – and there’s more about that here – with the newly regenerated Doctor lying on a very flea-infested looking carpet in U.N.I.T. HQ, but in many regards it was more of a celebratory send-off for The Brigadier and company than it was a jolting journey into the new and unknown. Obliged to help the United Nations Intelligence Taskforce see off an unashamedly King Kong-analogising threat from an increasingly expansive android, and after rejecting a series of overplayedly comically unlikely outfits including a Knave of Hearts, a Pierrot and a Viking – you cannot help but wonder if this may have had its origins in the brief timeframe when Michael Bentine was all but signed up for the role but pulled out when they declined to afford him script approval; how delighted they must have been with his eventual replacement’s noted enthusiasm for adhering directly to the dialogue that had been written for him – and flashing around his Alpha Centauri Table Tennis Club membership card which in itself raises logistical questions that we are possibly best advised not concerning ourselves with here, The Doctor finally gets around to tackling the Scientific Reform Society’s crackpot foot-shooting plans to use global diplomatic blackmail to, apparently, prevent women from wearing shorts with the iron-armed assistance of their expanding and contracting plastic pal who’s fun to be with. Despite the somewhat singular design that rendered it apparently on the constant verge of saying something conversation-stopping, The Giant Robot itself proved remarkably popular for an antagonist with in-built one-story obsolescence, inspiring not just two separate iterations of Terrance Dicks’ tie-in novel but also an action figure courtesy of the ever licencing-hungry Denys Fisher Toys, and enjoying increasingly dented pride of place in the Blackpool and Longleat Doctor Who exhibitions for years thereafter. Less remarked on, however, was the ‘Robot’s Eye View’ representation of its supposed field of vision, thickly and blurrily delineated into a series of smaller squares somewhat reminiscent of when an adult would lift you up to ‘have a look’ through the security glass inset on the exterior door of a workplace which you could never actually make anything out through anyway. Quite how Robot K1 managed to develop such a fixation on Sarah Jane Smith when it only ever saw her in a procession of smaller squared-off images akin to a sheet of distorted postage stamps, let alone enact its assigned duties as part of Think Tank’s plot to hold the world’s governments to ransom, is a question perhaps not best placed under too rigorous an evaluation. Still, it’s probably more worthy of one than certain other robotic hench-droids…

IIIIIIIIIINN THREE… A Robot!

Produced by Central Television between 1981 and 1995, Bullseye was a Sunday afternoon game show in which intemperate club comic Jim Bowen marshalled dart-chucking teams of members of the public who generally had difficulty in making it all the way from one end of a one-word answer to the other through a series of suitably oche-orientated rounds necessitating resolutely failing to hit the portion of the dartboard bearing the preferred category (“Geography we’d like”) with audience-pleasing animated interjections from stripy-shirted taurean mascot Bully, most famously seen in the opening titles arriving at a bawdily heaving pub with a coach full of ‘the lads’ and, erm, visiting the gents in the ad break bumpers. The ultimate aim or indeed lack thereof was to make it through to the final round, where they were joined by a celebrity darts professional in the hope of securing lavish riches from Bully’s Prize Board, with an option to gamble on a chance at a Special Prize such as a caravan or a fitted kitchen, but otherwise constituted a parade of lower quality escapees from that page in the Argos Catalogue that you could only ever find when you weren’t actually looking for it including carriage clocks, blank video cassettes, televisions with attached ‘remote’ controls – inevitably depicted showing episodes of Bullseye – and a seemingly limitless supply of home barbecues. Constructed from dull yet glaring alloys of indeterminate chemical composition, these shabby constructions bore more resemblance to a breadbin placed on top of an old-skool pushchair framework than anything that you might have seen Tom Vernon alliteratively showboating around with on BBC2, and indeed looked for all the world like they were falling apart before they had even been constructed. Although the episode in which he romped home to dart-skewed victory has yet to resurface on Challenge TV, Sontaran reconnaissance officer Weam Styre had evidently done quite well on Bullseye at some point as he deployed one of these barbecues to guard his spaceship while he conducted his strategic assessments of an abandoned future Earth in The Sontaran Experiment; it was eventually short-circuited by The Doctor but to be honest he could probably have taken it out of active service by whacking a couple of Bernard Matthews’ Turkey Hamwiches on it and expecting it to attain a temperature above ‘none’. It certainly attains a truly Jim and Bully-worthy degree of cheapness and nastiness by virtue of all of its appearances in The Sontaran Experiment being shot outdoors on videotape, as indeed does the scrubland posing as Earth ten thousand years in the future, which has the unintentional look of a particularly weather-abandoned location report from BBC rural current affairs show Countryfile. Which in fact wasn’t the only John Craven-adjacent magazine show to find its way in to this series of Doctor Who by proxy…

“No Doubt You’re A Bit Surprised To See Us In The World Of Doctor Who!”

Such were the febrile working relations of the time, with industrial action staged in response to pretty much everything probably including some actual in-progress industrial action itself, that it is actually difficult to find a UK-made television programme of the early seventies that wasn’t in some manner affected by strikes and walkouts. Indeed, in Doctor Who‘s case alone, it’s the primary reason why Spearhead From Space had to be made entirely on film and entirely on location, as you can find more about here. Many more minor and on occasion major instances of tool-downing would impact Doctor Who‘s production over a decade that was in all honesty riven with them, and late in May 1974, a disagreement over scene-shifting duties and responsibilities resulted in some studio sets for Robot remaining in situ after they should have been replaced by others, necessitating some hasty on-set lateral thinking and careful shooting around of items that should not have been where they were but nobody dared move them for fear of further complications. This also had the slightly more inconvenient consequence that the sets then could not be cleared to make way for that afternoon’s edition of Blue Peter, meaning that Pete, John and Lesley – and indeed Petra, Shep and Jason – had to present the show from an assortment of offices, laboratories and cells rather than their usual triangular shelf-punctuated white void. To be blunt, outside of less than half of an acknowledgement of the presence of the TARDIS right at the start, they really don’t dwell on the Doctor Who situation at all, despite the supposed ‘special relationship’ between the two, and prefer instead to get straight on with some business about a ‘very unusual’ pet shop in America that does horoscopes for dogs or something. Also, later on, they got around to a ‘make’ that they actually bothered seeing through to completion, unlike certain other grand ambitions on open display in Doctor Who at the time…

My Skystriker! My Glory!

From the Cybermen who sound more like that bloke announcing indirectly to the very long queue behind him that we have come to a pretty pass indeed if a leading high street let me fi- let me finish if a leading high street bank can only have eight cashiers on duty on a day when very busy people need to use the bank to the very fact that, vulnerability to the primary export of the ‘Planet Of Gold’ or otherwise, they by definition should not have been capable either of seeking or desiring ‘revenge’, there are many deep-set issues with Revenge Of The Cybermen although arguably none more self-condemnatory than the fact it is a story that it is more interesting to read about the hair-raising incident-strewn making of than it is to actually watch. In fairness, gold-proffering Cyber-botherers the Vogans are well realised for the time and have some entertaining haughtily bicker-driven exchanges, so when their lead ‘guardian’ Vorus exclaims ‘My Skystriker… MY GLORY!’ in an amusing over-enunciated fashion whilst collapsing to the floor, you could be forgiven for expecting the decades-in-the-making magnum opus projectile he’s just launched in a bid to see off the Cybermen to be a visually stunning example of alien technology searing through the stars in a scorch of special effects. Instead, we just get extremely over-exposed and impossible to effectively match stock footage of an actual Saturn V rocket taking off. Doubtless there have been innumerable sub-He’s Free Is Nelson Mandela fan gambits aimed at explaining it away as Magrik and company constructing it from remnants of a recovered ‘lost’ NASA rocket et al but this is little more than a deflection from the harsher fact of the matter that the majority of younger viewers glued to Revenge Of The Cybermen would also have been similarly avid followers of the real life Apollo Missions, and would have been able to spot a shoddily-made featureless Cybermat when they were being sold one. There’s convenient expense-saving ingenuity and there’s having what verges on outright contempt for the intelligence of your audience. Though – astonishingly – it wasn’t even the most visually risible element of Revenge Of The Cybermen…

Why The Long Face?

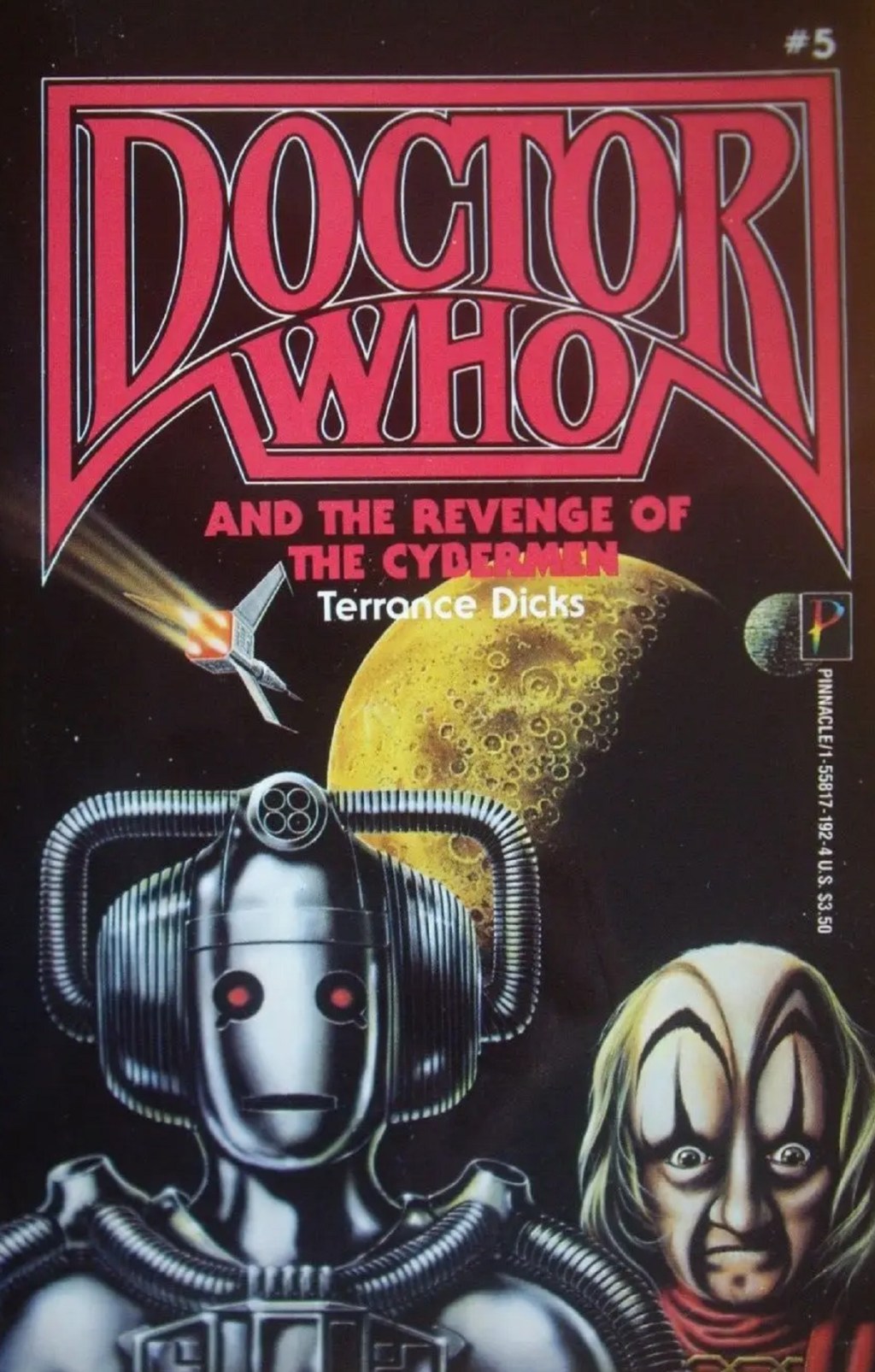

It may not exactly be one of the more sterling titles in the range, but all the same Terrance Dicks did a creditable job in turning some muddled and self-contradictory scripts into the at the very least readable Doctor Who And The Cybermen, buoyed and bolstered by his understanding of and evident liking for the regular cast even if his descriptions of the Vogans appear to be based on something else entirely that he may even have just made up himself based on nothing. On its initial publication by Target Books in 1976, Chris Achilleos gave it a fittingly adequate yet undistinguished cover featuring Tom Baker apparently in the middle of a swarm of bees descending on a melted Crunchie with competently replicated publicity photos of a Vogan and a Cyberman facing off against each other, replaced for a later reprint by Alister Pearson’s arrangement of the latter adversaries in inset circles disturbingly reminiscent of the opening caption from Tom And Jerry. In 1979, however, Target licensed several of their Doctor Who titles to Pinnacle Books for American publication; as well as dangerously parochial references like ‘jelly babies’ being changed to thoroughly all-American counterparts and an unhinged introduction from perpetually worrisome loose cannon Harlan Ellison in which he basically offered to fight anyone who didn’t watch Doctor Who, Doctor Who And The Revenge Of The Cybermen now came in an all-new cover apparently written by someone working from a video copy in the wrong aspect ratio whilst being gradually boxed in by one of those things they used to use to measure your feet with, in which the two by now familiar opposing view-holders over the universal proliferation of gold appear bearing elongated heads that in moderately different circumstances would have bagged them both a side hustle appearing in mid-eighties Tefal adverts. The Vogan bearing a disconcerting resemblance to some sort of art deco clown who ended up sighing ‘but doctor… I am Tyrum!’ in the slough of his despond is ridiculous enough, but the elongated Cyberman looking at himself in the back of a spoon frankly makes it seem faintly absurd that Mary Whitehouse had considered them to pose such a liability to tear society’s moral fabric asunder only a couple of years previously. Still, they’d have inspired plenty of jokes if they’d walked into a bar with Harlan. If he could stop punching people for liking A Man Called Sloane instead for five minutes. Meanwhile, speaking of things that were way too long by normal and rational standards…

“Faithful Old Scarf…”

Reputedly literally fashioned in true can-I-ask-a-practical-question-at-this-point-are-we-gonna-do-Stonehenge-tomorrow-night fashion from an accidentally over-ordered over-abundance of varyingly hued wool, The Doctor’s seemingly endless multicoloured scarf – as fan-written reference works are apparently legally, morally and ethically obliged to refer to it as – is arguably second only to that non-changing Police Box itself as the general public’s most instantly associative and recognisable aspect of Doctor Who iconography. Whether forming an essential part of the wardrobe of any fan who habitually dresses as ‘their’ interpretation of The Doctor presumably in the hope that a BBC producer will spot them on the street and exclaim ‘you’re just what we’ve been looking for – welcome aboard!’, enabling jocular letter-writers to Points Of View to sign off with a chortlesome ‘perhaps The Doctor could use his scarf – to trip up Michael Grade!’ or facilitating Syd Little’s immediate recognition that through the donning of a cursory hat and single-coloured scarf Eddie Large had ‘turned into Doctor Who’, it almost immediately became powerfully effective shorthand for Doctor Who to the extent that it did not even need to be in any way accurate or evocative, just there. What is rarely remarked on, however, is just how much of that was down to Tom Baker’s performance, and in particular his usage of the scarf as essentially an extension of his acting technique. You never really got Jon Pertwee saying ‘arrest the frock coat, then’ or William Hartnell using his pince-nez as a three in one lockpick, tripwire and sacrificial implement for checking whether floors were electrified, but right from the outset he uses the scarf as part of his performance and persona and the writers very quickly began to pick up on this too, resulting in a sort of seemingly endless multicoloured loop of wool on wool creativity. If he’d just gone around simply wearing it, it may never have caught on in quite the same way, and it is perhaps telling that even three years into the role people were still asking what in the absolute fuck Peter Davison’s sprig of celery had to do with anything and indeed continued to do so even after it was ‘explained’. While the ingenuity of whoever staged the marathon knitting session in the first place should not be disregarded, it was almost as though Tom Baker considered the scarf an unofficial member of the regular cast. Which was a fairly high set thespian bar at that point…

WhataboutSarahandHarryyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyy?

Out of all of the shorter-stay regular TARDIS travellers, few seem to inspire as much genuine affection as clumsy and blustering military medic with a sturdy duffle coat and a mean right hook Harry Sullivan. The very first character to get their own full-scale proper solo spin-off novel, very nearly brought back for the twentieth anniversary celebrations, regularly referenced in genuinely touching moments in The Sarah Jane Adventures and star of a Big Finish audio play in which he accidentally caused himself to trend on Instagram, Harry has always been a much loved fixture of what for want of a better term that’s still better than ‘Whoniverse’ shall have to be identified as the ‘expanded universe’, which makes the contrast between this enduring adulation and the amount of time he actually spent on screen all the more jarring. With several older actors considered before Tom Baker came to their attention, the production team had envisaged Harry as a convenient handler of the more ‘action’-necessitating plot details; with the eventual new Doctor thundering off and performing them himself before the script had even landed in his hands, Harry was considered surplus to directional requirements and quietly if suitably comedically let go at the end of the run. Philip Hinchcliffe would later remark that this was a mistake, however, and not without good reason; so much more than just a relatively strong-armed line-feed, Harry’s combination of meddlesome buffoonery, square-jawed loyalty and fervent belief that sometimes a well-placed and well-deserved thump is the only language these dashed bounders speak fitted in incredibly well with the established Sarah Jane and the brand-new Doctor – who nonetheless denounced him as an ‘imbecile’ at a television speaker-rattling volume – and the audience certainly took to them as a team; it really is a shame that they did not get to continue their tremendous rapport further, especially considering how well suited he would have been to the more macabre stories that lay ahead. It is also worth considering just how closely their dynamic was mirrored by that of The Doctor, Rose and Captain Jack at a moment when Doctor Who could scarcely afford to make any false moves and obvious tried and tested audience-pleasing gambits were being skilfully worked in pretty much everywhere you looked. As throwaway a segue between scenes as it may have been, Tom Baker’s echoing elongated single-word “WhataboutSarahandHarryyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyy” to the evaporating Time Lord at the outset of Genesis Of The Daleks feels like a powerful affirmation of their strength and popularity as a unit; he really doesn’t want to embark on this frankly daunting unwanted assignment without having them to hand, no matter how liable Harry is to get his foot caught in a giant clam at the first available opportunity. As for how they ended up caught up in that frankly daunting unwanted assignment in the first place…

Uh Oh, Wirrn Trouble…

Although Robot ostensibly raised the curtain on both a new Doctor and a new era, it was also effectively tactfully drawing a discreet line under the previous one before properly moving on, and the new regime itself did not really make itself evident until the following story; upon which it really did make itself evident in no uncertain terms. At something of a slight remove from writer John Lucarotti’s original story breakdown where The Doctor drove The Wirrn out into space with a Jacob’s Club or something, Robert Holmes’ overhaul of The Ark In Space took Doctor Who into realms of horror in general and biohorror in particular where it had never even previously given so much as a passing thought about venturing, let alone dared to venture, with the Nerva Beacon’s cargo of far-flung futuristic fugitives from a troubled Earth struggling to fend off a parasitic life form literally eating away at them. Travelling down to Earth to repair the transmat link that will allow the now Wirrn-free voyagers to return to the potentially now once-again inhabitable planet, The Doctor and company discover that they aren’t the only ones with designs on the deserted landscape and Field Major Styre is brutally thick-headedly conducting The Sontaran Expriment on a handful of scarcely representative stranded technicians. Intending to return to the Nerva Beacon, they are instead waylaid by the Time Lords and sent back to change history by preventing the Genesis Of The Daleks, returning to the TARDIS at its conclusion by way of a ‘Time Ring’ that, presumably on account of the eventual moderate modifications to the timeline, deposits them back on the Nerva Beacon centuries before they left it, with the TARDIS very gradually taking its merry time making its way back to them from the future, where they fail to see very much actual enacted evidence of the Revenge Of The Cybermen. Although the interlinking narrative concept was fairly quickly retired, the much darker yet sophisticatedly comedic tone that this new series established and indeed the new lead actor himself resonated so strongly with the viewing audience at the time that it is small wonder that so many will not unreasonably identify this as the best ever series of Doctor Who, despite it also including two stories that they at best tactfully omit to mention. After all, its reputation does pretty much hinge directly on one story – and one character – in particular…

“Yes, I Would Do It…”

From Sydney Newman scrawling ‘NUTS!’ on some vague and high-falutin’ ‘meaningful’ mythology nobody asked for on the original initial Doctor Who outline document all the way to the show being airlifted to Disney+ to do battle with The Falcon And The Winter Soldier and Chrissy And Dave Dine Out rather than sitting alongside all those embarrassing flops nobody watches like Gladiators, the history of Doctor Who is strewn with pivotal moments that are frequently discussed and debated with even more fervour than more important questions like why Polly has The Doctor’s hat on at the end of The Underwater Menace, but there is one that is arguably more pivotal than most and yet invariably conspicuous by its absence from such discourse – Terrance Dicks politely suggesting to Terry Nation over lunch at The Ivy that maybe they’d done stony-faced rebels with tedious names being sent on a mission to take down The Daleks a few too many times now and it might be an opportune moment to finally tell the story of their, well, genesis. This was far from the first occasion on which an at least halfway official attempt had been made to document and codify the politico-evolutionary background to The Daleks – you only need to look at the largely uncannily similar chronicle of Skaronian scientist Yarvelling in the TV Century 21 strip, or all those tie-in books from the mid-sixties claiming that Daleks were morally forbidden from acknowledging Quink or whatever it was – or indeed to establish some form of hierarchical command, which at any given moment could switch between The Black Dalek, The Gold Dalek, The Dalek That Painted Itself In ‘Showbiz’ Candy Stripes Or Something Although Apparently It Also Didn’t or that Habitat salt-grinder posing as the ‘Emperor’ Dalek, or indeed its spacehopper-headed comic strip counterpart with a ready supply of handy inflatable body doubles. The moment that Davros abruptly swung into view, however, everything equally abruptly swung into place with him, and it was suddenly as though the Dalek mythology had never been in question at all. Visually repugnant yet chillingly charismatic, morally repugnant yet coldly and unshakeably logistical in his beliefs, ferociously intelligent and calculating yet stark staring mad, Davros was conceived by Terry Nation as a genius with the potential to heal the universe driven to insanity by his own ruthless self-inflicted physical and genetic existence-extending cerebral and medical modification at the expense of the less ‘important’ parts of his anatomy – no matter how uncomfortable subsequent corresponding modifications to his backstory by other writers may make some audiences feel now, that’s not what the character really is and it’s both unreasonable and more than a little troubling to denounce and disregard him on that basis – and from the brilliantly sculpted mask to Michael Wisher’s powerfully effective economy with his movement and speech, whether the character and the performance hooked viewers on account of the odd twisted sense of humanity and egotistical vulnerability that almost made you want him to succeed or because it was half of a man and half of a Dalek and therefore the best thing EVER, Davros is a screen villain with few equals and if you want some stunningly effective evidence of this, then sidestep the usual ‘that power would set me up above the gods’ clip show-friendly debate and take a look instead at the scene where he forces The Doctor under extreme duress to outline every known set of future events that ever resulted in The Daleks being defeated. Which admittedly does cut to another scene partway through but that’s probably just because he had to describe all of those rope bridges. Davros, of course, is almost certainly a large part if not the largest of the reason why Genesis Of The Daleks itself is so routinely cited as the greatest Doctor Who story of all time – but should it really be that easy to make that degree of distinction?

Is Genesis Of The Daleks REALLY The Best Doctor Who Story Ever?

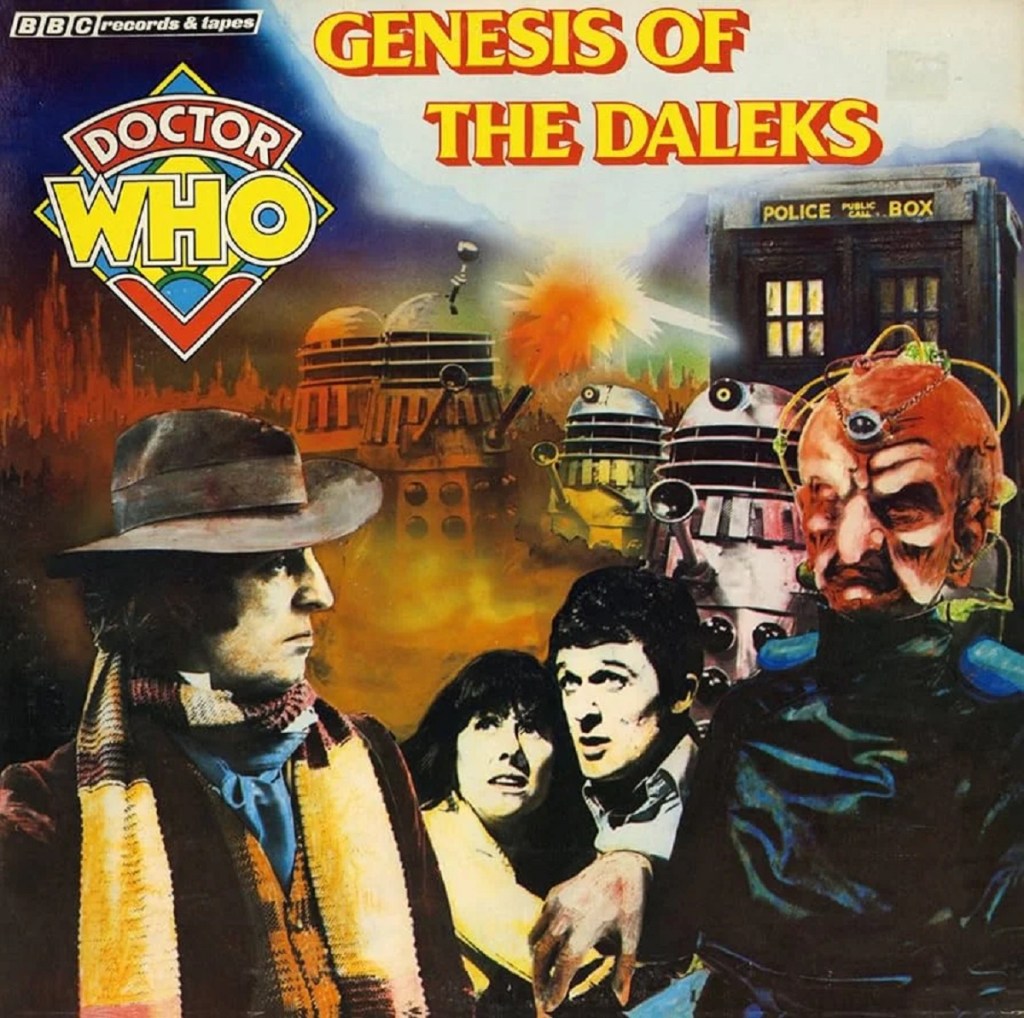

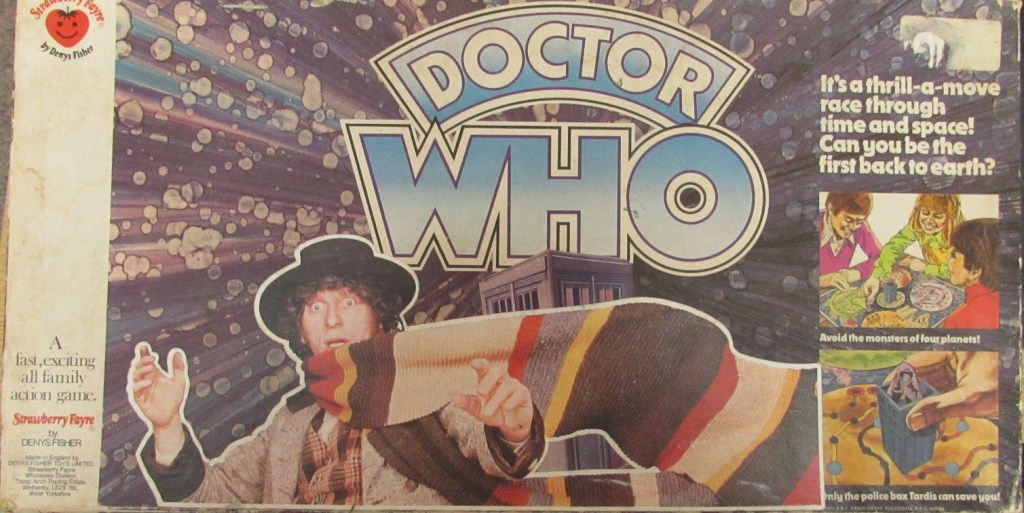

Mischief-prone wags might try to claim with a straight face that it’s Rings Of Akhaten, aesthetically cerebral types might make an esoteric case for the low-key emotional punch packed by The War Games and stand-up comedians might respond “aw man, bro – I thought you were going to say the one with the Weeping Angels, bro – give me something to work with bro!”, but when it comes to lists, polls and those ‘World Cup’ things that you are obliged to ‘rt for larger sample’ of the best Doctor Who stories ever made, Genesis Of The Daleks will more often than not be at the very least hovering around the top of it though more usually triumphantly seeing off all other competition bar none. Even the one with the Weeping Angels. There is little doubt, of course, that it is a remarkable achievement with the cast, crew and writer all working at the absolute top of their game, with a variety of contradictory moral points addressed in unflinching yet spellbindingly entertaining fashion and never at any points feeling like it’s a six episode story that knows it and doesn’t care, but there is still an important question to be asked about its reputation, and one that even Davros might hesitate before answering at that – how much of the loftily elevated status that Genesis Of The Daleks enjoys is down to the affection that it is held in rather than its actual – if admittedly undisputed – quality? Rapturously received at the time, and possibly even more so on account of the fact that Mary Whitehouse did not receive it remotely rapturously, it was soon given a well above average tie-in novel treatment by Terrance Dicks, and the exposure did not end there; it was repeated in a rearranged movie length edit over Christmas 1975, and then again – staggeringly for a time in which extant old episodes of Doctor Who were so rarely seen again that they may as well have been wiped too – as two forty five minute instalments fashioned from three episodes apiece in 1982. More significantly, an entirely different edit with new linking narration from Tom Baker was released as an album by BBC Records And Tapes in 1979 – you can find out much more about the story behind that and the label’s other Doctor Who-related releases here, incidentally – and without any hint of hyperbole or exaggeration there is a good case for arguing that this is the most significant item of Doctor Who tie-in merchandise ever. For many, and for many years, this was the closest that it was possible to get to actually owning some actual Doctor Who that you could enjoy at your own convenience and leisure and that’s essentially exactly what everyone did, listening to the album so avidly and so often that there are more individuals than you might expect out there who can recite both sides word and sound effect perfect right the way through without pausing. There is little doubt that this degree of enduring affection through availability and repetition will have some bearing on anyone’s opinion of Genesis Of The Daleks over and above any rational critical analysis, but we have to be honest here – that is true of any Doctor Who story and indeed anything similar from any other series or indeed any other media for that matter, and that’s exactly as it should be. Responses to art and culture should always be as emotive as they are coldly and hardly factual, and after all, it’s only really the same sort of reaction that might inspire somebody to write nigh on sixteen thousand words in defence of Time And The Rani. Not that anyone would have done that. Especially not here. Anyway, the upshot of all this is that your personal feelings about your favourite story should be more important than anyone else’s militantly quantified defined and enforced assessment of ‘best’, and while Genesis Of The Daleks is unutterably fantastic, some may personally like other stories better and good for them. Unless it really is Rings Of Akhaten. There may even be those who consider whatever was going on with that Ludo-based thrill-a-move race through time and space in the other major item of merchandise related to this particular run of Doctor Who – Denys Fisher’s Tom Baker sticker-boxed plastic TARDIS-bolstered Doctor Who board game, although there’s much more trying to make sense of that here – the ‘best’ story. Although if they do, they really ought to admit to themselves that it’s the same one that was used in pretty much every other seventies board game based on a television series…

Anyway, join us again next time for a possibly non-existent suit of fairy lights, the shadowy ‘Fourth Kraal’ conspiracy, and Sutekh’s Gift Of Ritz Cheese Sandwiches…

Buy A Book!

You can find the story behind the Genesis Of The Daleks album – and a lot of other Doctor Who-related releases, some of which have escaped even the most dedicated researchers until now – in Top Of The Box Vol. 2, a complete guide to every album released by BBC Records And Tapes. Top Of The Box Vol. 2 is available in paperback here or from the Kindle Store here.

Alternately, if you’re just feeling generous, you can buy me a coffee here. AND THROUGH THE DALEKS I SHALL HAVE THAT COFFEE.

Further Reading

You can rewind back to the end of Jon Pertwee’s stint as Doctor Who – and Tom Baker’s first appearance – in It’s Still A Police Box, Why Hasn’t it Changed?: Shout Out To My Exxilon here.

Further Listening

There’s tons of further Doctor Who-related chat, including a look at a certain other Tom Baker-narrated audio adventure from slightly further into his run, in Doctor Who And The Looks Unfamiliar here.

© Tim Worthington.

Please don’t copy this only with more italics and exclamation marks.