There are those who will tell you – probably regardless of whether you ask them to or not – that the greatest opening line in movie history is either “A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away…”, “As long as I can remember, I always wanted to be a gangster” or “I believe in America”. There are probably also those who would counter that it is actually “Once upon a time… no it wasn’t once upon a time”, “We shouldn’t be here when it gets dark” or even “Mission successfully completed: Trailblazer Desmond Brock has safely returned to Space Podule Exxon Mark IV”. As far as I’m concerned, however, the greatest opening line in movie history isn’t an actual line of dialogue or even a caption. It’s a credit. And it’s “Python (Monty) Pictures Ltd. in association with Michael White presents…”.

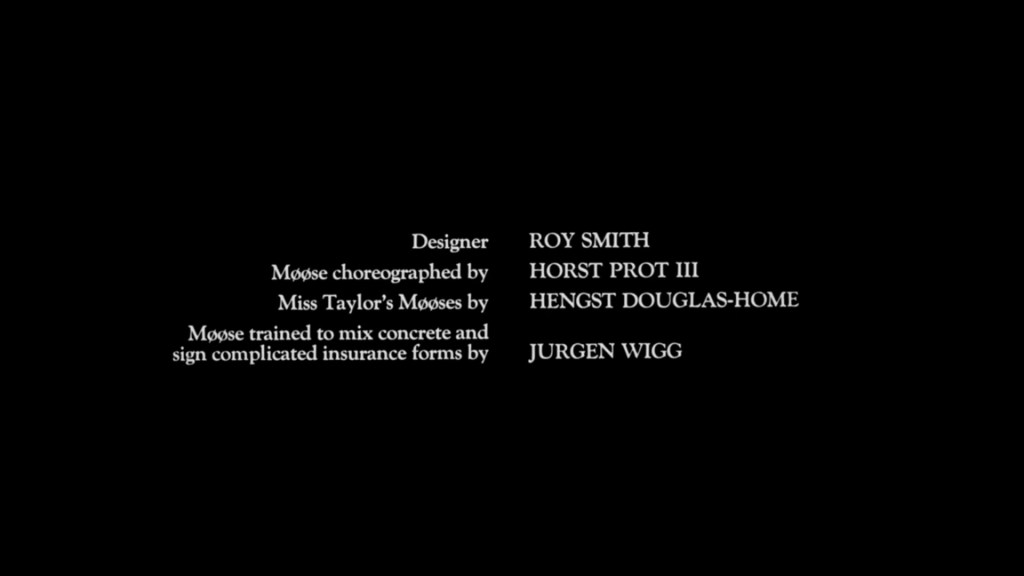

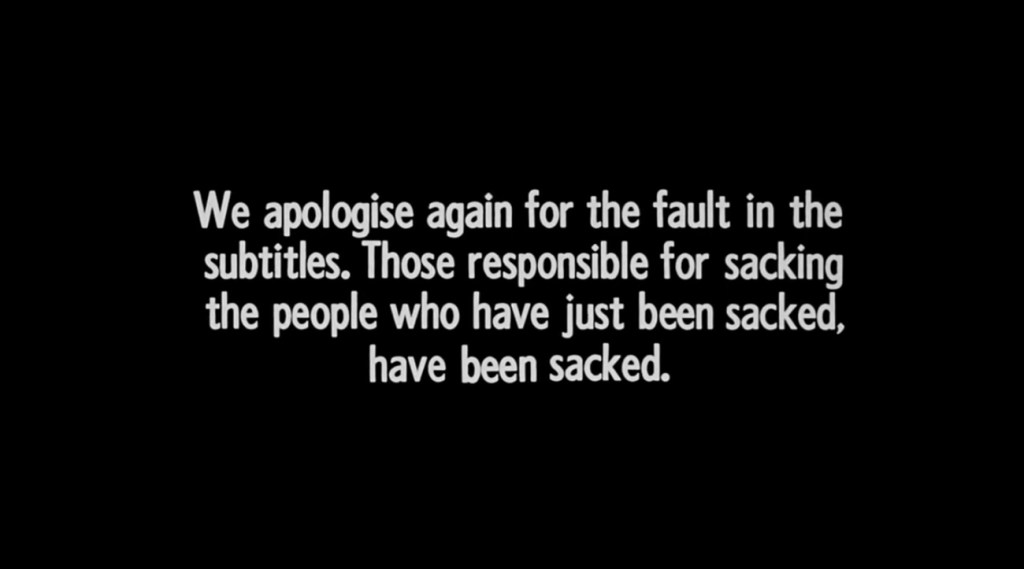

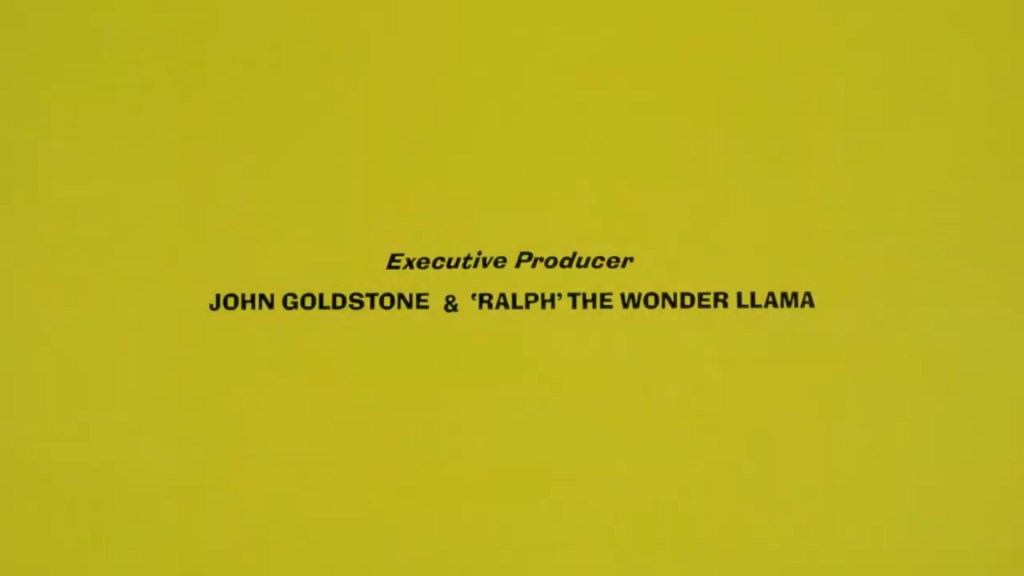

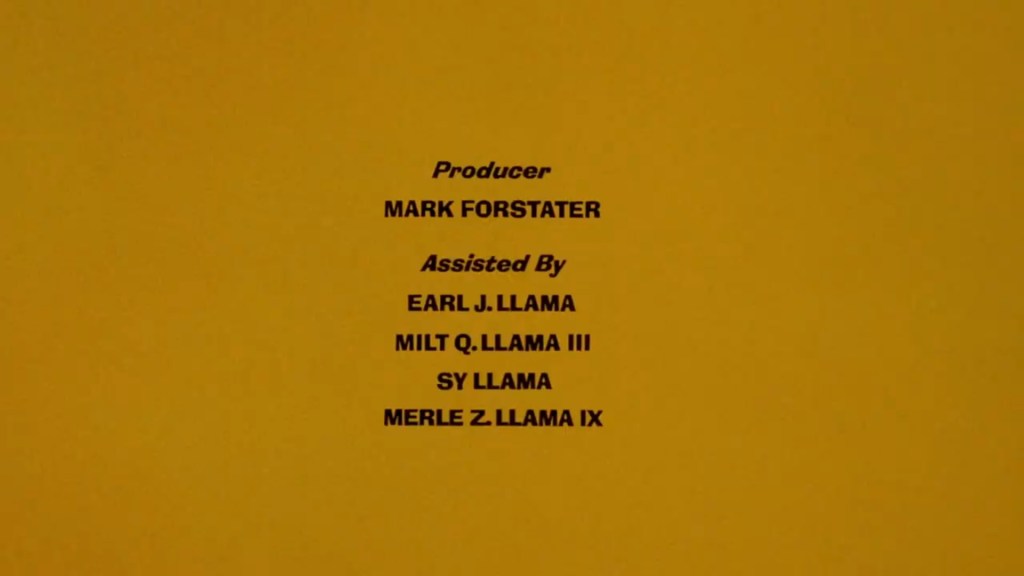

Michael Palin has often suggested that if you ever needed to define ‘Monty Python’ to someone with a single sketch, you should show them the Fish-Slapping Dance; this is an entirely correct suggestion – and he should know – but if you ever also needed to illustrate their complete and utter mastery of meddling with anything and everything they could get their collective hands on in the name of silliness and humour, then you probably couldn’t do much better than the opening credits of 1975’s Monty Python And The Holy Grail. Opening with portentous orchestral thundering and stark white credits on an equally stark black background – with a copyright disclaimer signed by ‘Richard M. Nixon’ – they suddenly judder to a halt when someone notices the appended translations, holiday tips, cinema guides and warnings about potential moose attacks in possibly not entirely accurate Swedish. The individual responsible is promptly sacked and it starts up again for a fraction of a second before the inevitable happens, and the individual responsible for sacking the individual who has just been sacked is sacked. The orchestra strike up a sweeping romantic serenade and the credits resume, only to wind down once again when the additional moose-handling credits are spotted. Pretty much everyone involved is sacked, and the credits are completed in an entirely different style at great expense and at the last minute – thanking legions of llamas while a Mariachi band whoop and holler with disconcerting enthusiasm and the projector suddenly seems to be in need of a new bulb fitting. Way above the level of cursory ‘funny’ credits, every joke is perfectly pitched and perfectly timed, including the choices of and changes in music. It has little to do with The Holy Hand Grenade Of Antioch or Sir-Not-Appearing-In-This-Film, but it would be difficult to think of a more effective way of setting the tone for them.

Although the haphazardly interrupted selections evidently were neither recorded nor intended as ‘comedy’ music, as the credit for ‘Additional Music’ from prolific stock music library DeWolfe arguably makes abundantly clear, their use to facilitate gags in the opening titles of Monty Python And The Holy Grail somehow managed to make them, well, funny. The Pythons had an uncanny and unparalleled ability to find amusing absurdity in the unlikeliest corners of the thoroughly mundane, and presumably – much as they did when originally picking out The Band Of The Grenadier Guards’ 1967 reading of John Philip Sousa’s Liberty Bell as the theme music for Monty Python’s Flying Circus – alighted on those three particular pieces of music while wading through library records, fell about laughing for reasons they were neither able to nor wanted to define, and set about working out exactly how and where to cue them in to the opening titles. If you wanted to get hold of them to fall about laughing for your own reasons that you were neither able nor wanted to define, however, then you were out of luck.

Although some other DeWolfe cues did put in an appearance, none of them were featured on The Album Of The Soundtrack Of The Trailer Of The Film Of Monty Python And The Holy Grail – surprisingly, as you might think that an album that even had its own bomb threat might have found room for something approximating ‘opening titles’ – but some unlikely and unexpected clues to their identity could be found hidden away in that other commercially available reminder of the ladies of Castle Anthrax from the pre-home video age. In amongst the revelation that Graham Chapman’s policeman is called Inspector End Of Film, the stage direction ‘FX: SPLASH, GURGLE’ and the original entirely abandoned attempt at the script which is more or less a pencil sketch for what became series four of Monty Python’s Flying Circus, Mønti Pythøn Ik Den Hølie Gräilen (Bøk) also includes a timing chart representing the two audio tracks that were cut together to make up the opening titles, identifying the individual musical inserts under the titles Wide Horizons, Ice Flow, Country Wide and Mexican Busker. Although in fairness there were probably not very many people looking for them, anyone who was at least had the titles and the fact that they were published by the DeWolfe music library to go on. So how would you go about finding them?

Well, let’s be upfront about this – nowadays you can probably just type ‘monty python llamas music off is what’ into the average search engine and find the artist credit, year of release, catalogue number and even the running time straight away, although it would almost certainly ask you if you ‘meant’ some band called Llama Moose with three gigs to their name instead. There was a time, however, when they really were just titles of tracks on records that were never intended for commercial release, and the likelihood of identifying them in any meaningful sense was as remote as, well, identifying the music from the ‘Blackmail’ sketch in Monty Python’s Flying Circus – Roving Report No. 2 by Jack Trombey and The International Studio Orchestra from the 1968 DeWolfe album Roving Report, in case you were wondering – so with this and the fact that nobody ever really seems to have anything to say about the compositions or the composers themselves in mind, here’s a quick look at the music behind the mooses.

The three ominous elongated electronically treated piano thumps and accompanying nervy orchestral panic at the very opening of the opening credits are all that are used from Wide Horizons by the Pierre Arvay Ensemble, released as the opening track on Empty Horizons by DeWolfe’s specialist experimental imprint Hudson Music Company in 1974, apparently only a couple of weeks before the opening titles for Monty Python And The Holy Grail were assembled. The full piece continues for another four minutes or so in much the same sort of horror movie-friendly neo-classical avant-garde style, which probably will not come as too much of a surprise if you are aware that George A. Romero would later use several tracks from Empty Horizons in 1978’s Dawn Of The Dead.

Also heard in Dawn Of The Dead – although arguably more evocative of longboats and Vikings than zombies – Ice Floe as it is more correctly spelt was so seamlessly edited on from Wide Horizons that anyone studying that audio cue chart while watching the opening titles could have been forgiven for assuming that the latter was either listed in error or later dropped. The full version is not really very much longer than what is heard on screen, although after the point where the titles screech to a halt there is a repeat of the main melody and then, rather appropriately, an abrupt ending. Incidentally the phenomenally prolific Pierre Arvay worked mainly in library music, so you will probably have heard his compositions hundreds of times without ever realising; one track that might be more familiar however is Merry Ocarina from 1964’s Illustrations No. 2, used for many years to accompany the absurdist exchanges between Humphrey The Tortoise and his unnamed existential young female associate in the Children’s BBC arts show Vision On.

The suitably elegant and opulent accompaniment to the credit for Miss Taylor’s Mooses by Hengst Douglas-Home, Anthony Mawer’s Country Wide was recorded by the Hilversum Radio Ensemble for the 1961 DeWolfe album Autumn Serenade. Redolent of a lost world of Nina And Frederik and cinema decor with ideas above its station, the version used in Monty Python And The Holy Grail omits – perhaps somewhat ironically for The Pythons – a delightful introductory ‘bong’, although a decent amount of the full track ends up on screen, and while the rest of it continues much as you might expect that really isn’t anything to complain about.

Under a variety of permutations of the word ‘Ensemble’, the Holland-based Hilversum Orchestra would record for a huge number of DeWolfe composers, presumably due to some arcane workaround for tax, union or rights complications, while Anthony Mawer’s compositions enjoyed wider exposure than you might realise. Prima Bossa Nova and Follow That Doll enlivened, if that’s the right word, many an ethically dubious seventies sitcom and comedy film, while Follow A Star is often used to evoke the glamour of a bygone age including in 2019’s Booksmart, and the self-explanatory all-purpose Mediterranean Cruise frequently finds itself deployed as ‘intermission’-styled music and even showed up in Pam And Tommy. No really. Meanwhile anyone who owns the ‘Executive Edition’ of The Album Of The Soundtrack Of The Trailer Of The Film Of Monty Python And The Holy Grail will be all too familiar with Jeunesse. Country Wide itself has more recently shown up on a number of DeWolfe compilations, although there are those out there who will fondly point towards first having been able to identify it via an unexpected appearance in Britain’s Best Drives, a 2009 BBC Four series in which Richard Wilson set off in a procession of Morris Travellers and Ford Zodiacs to recreate recommended leisure drives from a fifties motoring guide, including a memorable stopoff in Whitby where he determined to find out more about “these goths I’ve been hearing about”. There were, apparently, some viewers who on hearing that music were unable to believe it.

Written by Keith Papworth, whose music was also prominently heard in Octopussy along with – slightly less prestigiously – Benny Hill’s television shows and the grotty British sex comedy ‘Adventures Of…’ series, Mexican Busker was recorded by The Papworth Combo for the 1969 DeWolfe album Dogsbody. It sounds at least in its original version somewhere between the b-side of an early seventies football team’s single and when the music on BBC Test Card G got a bit ‘lively’, although The Pythons elected to embellish it here with a chorus of ree-ree-yees en un estilo similar a ese boceto en la serie uno donde presentaron algunos datos interesantes sobre la llama (¡LA LLAMA!).

Given that The Album Of The Soundtrack Of The Trailer Of The Film Of Monty Python And The Holy Grail closing by shrugging “Well that’s about it, really – the film ends… mainly visually”, and the final stage direction in Mønti Pythøn Ik Den Hølie Gräilen (Bøk) is “[SLUSHY ORGAN MUSIC STARTS AND THE HOUSELIGHTS IN THE CINEMA COME ON… ORGAN MUSIC CONTINUES AS THE AUDIENCE LEAVE]”, it’s not really possible to debate whether Monty Python And The Holy Grail has a better closing line than “I’m an average nobody – I get to live my life like a schnook” or even “I’m not sure how I got here, has do to with Spider-Man I think… I’m still figuring this place out but I think a bunch of guys like us should team up and do some good”. You’d be hard pushed, however, to find a better closing credit than “Directed by 40 Specially Trained Ecuadorian Mountain Llamas, 6 Venezuelan Red Llamas, 142 Mexican Whooping Llamas, 14 North Chilean Guanacos (closely related to the llama), Reg Llama of Brixton, 76000 Battery Llamas from ‘Llama Fresh’ Farms Ltd Near Paraguay, and Terry Gilliam and Terry Jones”. Don’t tell Martin Scorsese though. He probably wouldn’t be very amused. Even though as long as he can remember, he’s always wanted to be a llama.

Buy A Book!

You can find an expanded version of Special Møøse Effects: Olaf Prot, with much more on the background to those credits and those library music tracks, in Keep Left, Swipe Right, available in paperback here or from the Kindle Store here.

Alternately, if you’re just feeling generous, you can buy me a coffee here. Preferably not a Swedish one, though. Even if the subtitles do recommend it.

Further Reading

What number did Life Of Brian get to in Empire Magazine’s 1995 poll of the best movies of all time? Find out in The 100 Greatest Films Ever Made? here.

Further Listening

Why was a young Grace Dent terrified of Monty Python’s Flying Circus? Find out in Looks Unfamiliar here…

© Tim Worthington.

Please don’t copy this only with more italics and exclamation marks.