Published by Hodder Wayland in November 1980 – scarcely a month after the in-studio events that it captured were actually seen on screen – A Day With A TV Producer was part of a series of educational books aimed primarily at libraries and classrooms that also elsewhere spent an allotted nine to five or thereabouts with amongst others a footballer, a nurse, an airline pilot and a vet. On this occasion, however, the profession in question was a slightly more opaque one largely involving, if the front cover photograph was anything to go by, casting a quizzical eye over a loosely bound script with a couple of oddly positioned BBC cameras in the background and all too familiar item of scenery all too prominently positioned in the foreground. At the outset of the the book, in the first of a series of vignettes purportedly charting the events of his average working day, we meet the TV Producer in question standing outside BBC Television Centre, grinning broadly and looking both driven by youthful vitality and like he simply cannot wait to get cracking on the show he has just taken over, posed with the distinct air of someone who understands the value of any and every form of publicity in whatever opportunity it may present itself; indeed, before his first story had even entered production, he had taken the opportunity to make a short appearance in a tangentially associated Blue Peter feature to talk up the upcoming adventures. The TV Producer who had shared his day with Hodder Wayland’s photographer was John Nathan-Turner, and – regardless of your perspective – Doctor Who would never be quite the same again.

Although barely into his thirties, John Nathan-Turner was already what could be considered a BBC veteran, having joined as a Floor Assistant in the late sixties and steadily worked his way up the ranks whilst working on a series of highly rated drama and Light Entertainment productions and forging several of what would later prove to be significant professional relationships along the way. His most significant professional relationship, however, was with Doctor Who, a series he had worked on sporadically and then regularly since 1969’s The Space Pirates, a story of which his most enduring impression was the proliferation of stairs in the BBC’s Lime Grove studios. He had served as a particularly effective Production Unit Manager for much of Tom Baker’s tenure, and in 1980, after the initial choices had not worked out and with his contribution towards the runaway success of All Creatures Great And Small very much on the drama department’s mind, they opted for a calculated gamble and offered him the role of producer of Doctor Who. As will become more than abundantly clear, John Nathan-Turner was and remains a divisive figure who in far too many respects to catalogue here was simultaneously both the very best and the very worst thing ever to happen to Doctor Who. What will also become more than abundantly clear, however, is that he was and remains a hugely misrepresented figure, perpetually beset by axes ground by those with professional, personal and entitled fan-engendered ‘opinions’ on his skill and value as a showrunner – particularly once he was unable to respond for himself – albeit never exactly helping himself with an increasingly reality-averse dependence on over-optimistic spin. Neither has his reputation been exactly enhanced by – and it would be remiss not to acknowledge this here – certain allegations of what could be considered less than professional conduct, although even this it has to be said has been wilfully and maliciously misrepresented by the axe-grinders and for a more considered yet fully appropriately judgemental assessment of what did and did not happen interested parties, if that is the right word, are directed to Richard Marson’s excellent JNT biography Totally Tasteless. The aspect of his tenure on Doctor Who that has been arguably misrepresented more than any other, however, is just what and how much of an effect and impact he had back in the Autumn of 1980. Faced with taking responsibility for a programme that was still hugely popular but very much set in its ways and at increasing risk of being left behind in a changing world, that had done its best to counter the not unwarranted accusations of excessive violence and horror but still found itself unable to shake them off regardless of how ludicrous The Horns Of Nimon may have been, and undermined by a BBC full of departments that appeared to believe that, as he himself put it, ‘it’ll do because it’s Doctor Who‘, John Nathan-Turner took the difficult decisions – and we’ve not even alluded to the most difficult one yet – and dragged Doctor Who firmly up to date for a new decade. Admittedly a new decade that was not always exactly welcoming to it, but the excitement and invigoration of that almost entire overhaul is too often played down in service of a ‘point’ that even the individual making it never quite seems able to arrive at, and it was an excitement and invigoration that at least initially almost everyone was excited and invigorated by. Most thrillingly of all – and as chronicled in charmingly contrived detail in A Day With A TV Producer, it was evident from the very first second of the very first episode bearing his implosion-backed credit…

Theme From The BBC TV Series Arranged By Peter Howell

At the exact moment that everyone and everywhere else – including many of the BBC’s own trailers – was exhorting all and sundry to embrace the exciting new world of ‘the eighties’ in a sort of lazer-zapped-on ‘calculator’ font, Doctor Who‘s opening titles and logo had not substantially changed since 1974, while – the odd additional ‘spangle’ aside – the theme music had remained more or less exactly the same for nigh on two decades. It may be easy to look back with the benefit of distance, hindsight and a tedious fixation with the ‘classic’ Diamond Logo and ask ‘so what?’, but back when Doctor Who was an actual ongoing workaday television programme hovering under the constant threat of budget cuts and even cancellation rather than a ‘brand’, it was a matter that was long overdue drastic attention. John Nathan-Turner was by all accounts particularly uncertain about the fact that Tom Baker now looked considerably older in the actual episodes than he did in the opening titles, and while this may not have been the greatest of his concerns – although it did provide an early hint towards the greatest one – when he assumed the producer’s ‘chair’ as Doctor Who Magazine insisted on calling it, it was certainly the most pressing. Out went the well-worn stretched backlit supermarket bag and photograph of Tom Baker looking ‘alarmed’ and in – courtesy of Sid Sutton, one of the BBC’s most talented, prolific and significant in-house Graphic Designers, who amongst his many other achievements only designed the actual bloody BBC Globe – came an unyielding void of eye-grating stars and a swanky new metallic-glass effect logo that looked uncannily like what you might have otherwise seen enticing you to peruse your newly-opened local video rental shop’s dazzling wares, and an up-to-date image of a decidedly jaded-looking Tom Baker who would probably have served only to encourage you to give your video shop a wide berth; ironic considering that he would soon become the face of BBC Video’s own selection of superbly-named ‘Video Tasties’. The resultant starfield, it has to be said, bears more than a passing resemblance to the refractingly-photographed cake on the cover of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop’s 1979 retrospective album 21, which perhaps suggests what then happened with the theme music may not have been particularly much of a coincidence. It is difficult to convey but at the same time impossible to overstate just how popular recent Radiophonic Workshop recruit Peter Howell was with viewers at the turn of the decade; having provoked a torrent of appreciative correspondence with his contributions to Jonathan Miller’s The Body In Question in 1978, amongst a flurry of ensuing engagements he was the first choice to provide theme music for quickly-derailed flagship live marathon arts show Mainstream and was considered such a selling point by BBC Records And Tapes that they even tried to launch him as a sort of budget-conscious in-house counterpart to Jean-Michel Jarre and Vangelis with his full-length synth wizardry-festooned concept album Through A Glass Darkly. If you’re interested in knowing more about any of these albums, incidentally, then you’ll find a lot more about them and plenty of other Doctor Who-related releases besides in Top Of The Box Vol. 2 here. With plans already in progress to shift towards using the Radiophonic Workshop for incidental music rather than the long-serving but increasingly outmoded Dudley Simpson, courtesy of an audition process that essentially involved them entirely rescoring a hefty chunk of The Horns Of Nimon, it undoubtedly made sense to ask their most prominent Fairlight CMI-twiddler to have a go at overhauling the theme music using – as profiled in several hundred million ‘behind the scenes’ features on BBC magazine shows – emergent studio technology, resulting in an entirely new version which sounded new and exciting and thrilling even just playing in the background of ‘Tonight… on BBC1!’ rundowns. As much as present day commentators might pour scorn on the supposed ‘soft rock’ arrangement of the theme tune – although quite which Hall And Oates number it bears such a pronounced resemblance to has never been clarified – and deride the logo which admittedly resembles something that you are now more likely to see hanging ill-positionedly in the window of a takeaway offering a disconcerting mishmash of cuisines alongside ‘VAPES’ and ‘NEWS’, it is both unfair and unreasonable to dismiss the impact that this brand new look had on blasting out of the nation’s television sets at a quarter past six on Saturday 30th August 1980; well, providing you actually saw it that is, and you can hear all about one unfortunate individual who missed the grand unveiling due to, ironically, being at the Doctor Who Exhibition in Blackpool here. Without a word of irony intended, John Nathan-Turner had succeeded in dragging Doctor Who into the age of The Hot Shoe Show, Einstein A Go-Go by Landscape and Radio 4’s The Chip Shop, and whatever reactions this may provoke now they are arguably immeasurably outweighed by the reception that they engendered at the time. It should stand to reason, then, that whatever followed that exhilarating first glimpse of the brand new Doctor Who opening titles and theme tune must have been equally dazzling and diverting…

Take Me Back To That Place That I Know

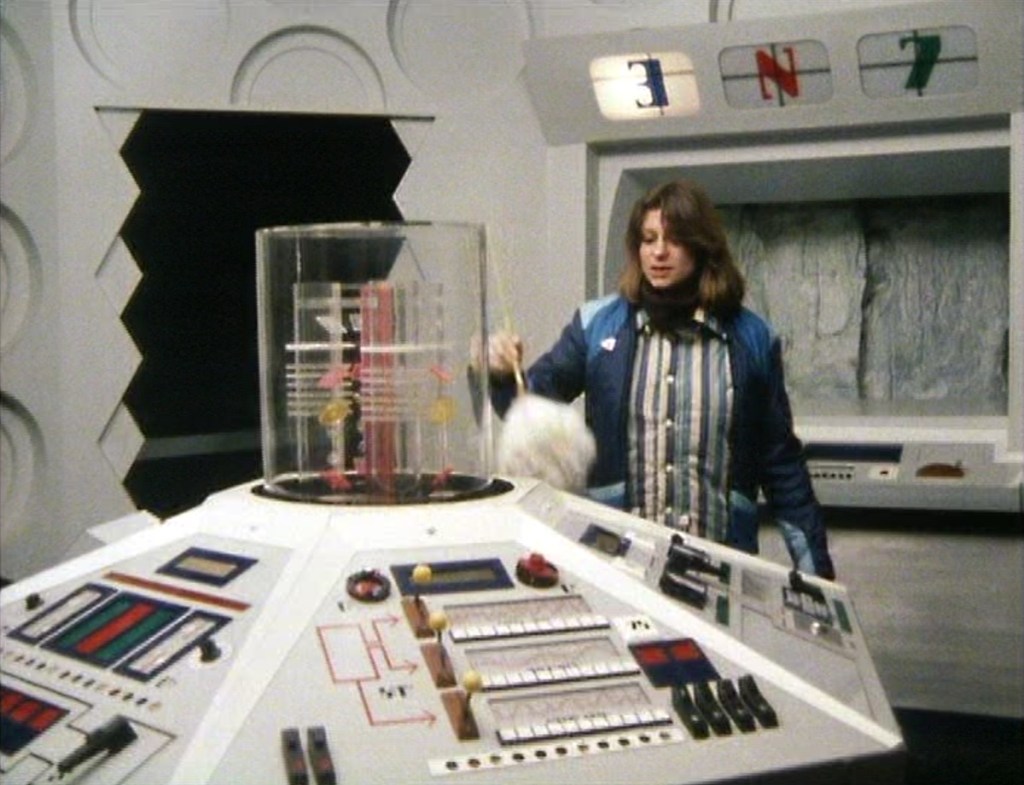

On paper – and indeed mostly on videotape – The Leisure Hive was the ideal story to launch the all-new all-improved eightiesed-up iteration of Doctor Who. Gleaming and futuristic yet economical and functional set designs, ingeniously deployed state-of-the-art video effects on loan from the Current Affairs department, an incidental score from Peter Howell so listenable and engaging that it was later siphoned off into a suite in its own right by BBC Records And Tapes, wittily incorporated ‘real’ science courtesy of incoming Script Editor Christopher H. Bidmead – who despite only remaining in this role for this one series would have an enormous and continually undervalued influence on the future directions of Doctor Who but who even in this look at his one set of stories in charge will probably be largely overlooked, but to be honest that’s how much JNT is always going to overshadow everyone else – and the actor David Haig sporting a hairdo somewhere between a failed attempt at launching a Pistachio Walnut Whip and what might have happened if Douglas Hurd had taken style tips from the ‘punk’ off Sorry, I’m A Stranger Here Myself. Even the emergent leisure industry boom that it sought to satirise was relatively topical and ‘new’. It would be interesting to know, however, how many viewers actually stuck around to witness any of this. With one eye on an opportunity for pre-series publicity and the other on an opportunity for the lead cast to indulge in a dash of light-hearted scene-setting regarding some recurring plot devices and indeed the entire ‘holiday’ theme, John Nathan-Turner suggested incorporating a short opening scene shot on Brighton Beach. Unfortunately, for reasons best known to himself, director Lovett Bickford interpreted this as meaning that the episode should commence with a full one minute and thirty seconds of an interminable tracking shot across nineteen empty deckchairs, occasionally punctuated by changing huts that hove into view then seem to remain motionless for an entire ice age, before alighting on one bearing an unresponsive Tom Baker with his hat pulled over his face. To make matters even less palatable for the passing casual viewer with half an inclination to see what ITV’s big new hugely hyped import Buck Rogers In The 25th Century was all about, the scene rapidly degenerates into wilful mistreatment of K9 as Romana, displaying a lack of forethought right up there with THAT cliffhanger from Dragonfire, not only assumes that the angular trundling robot dog is capable of retrieving a beach ball but actively encourages him to hurtle off towards the tidal mark, resulting in a Public Information Film-level flash of rust, sparks and seaweed and his convenient inactivity for large parts of the remainder of the story. The unofficial line always ran that K9 was popular with viewers but not with the production team – and this incident arguably serves as early notice of JNT’s own intentions towards the ‘AFFIRMATIVE’-chirruping mainstay – but that sort of popularity with viewers is disregarded at your peril and there must have been more than a few who were relieved to see a sort of metal Anne Widdecombe carrying a talking BBC Test Card G around its neck who seldom got into any hairier scrapes than getting stuck in a cupboard over on the ‘other channel’. Somehow requiring an entire two days of location filming, the sequence achieves little other than to suggest that the old-school BBC ethos has dug its heels resolutely into the shingle and is refusing all attempts to force it up to date. In something approximating a joke, The Doctor remarks that he has missed the opening of Brighton Pavilion twice, despite the fact that he has been there long enough to witness it eighteen times over, and the audience must have felt like they had been there for even longer. If they did manage to somehow endure this and stick around, however, then they may well have found themselves greeted by a reassuringly – and suspiciously – familiar sight…

Imps And Demons (And Foamasi)

Very much intended as a central pillar of ITV’s triumphant return following the epic channel-scuppering strike of 1979 – which you can read more about here, incidentally – Nigel Kneale’s Quatermass revival was in many senses a victim of its own troubled and surprisingly lengthy production history; striking an exceptionally downbeat tone in already exceptionally downbeat times, shorn of the intense cultural topicality it would have held back in 1973, struggling to compensate for the lack of the knowing tone so casually wielded by newer and more sophisticated competitors, and generally not succeeding in recapturing that mid-fifties thrill of pubs emptying so everyone could gather round the nation’s three and a half television sets to catch the latest deployment of an increasingly crackly cue from a Trevor Duncan library disc. One more positive aspect of the circumstantially muted anticipation, however, was that Arrow Books took the opportunity to reprint the three original Quatermass script books with new covers depicting the nominal villains – who in course in actuality are nothing of the sort – of the respective serials; hapless alien-infiltrated astronaut Victor Carroon for The Quatermass Experiment, ‘mark’-stricken Captain John Dillon for Quatermass II and one of the troublesome prehistoric Martian hobgoblin thingymajigs for Quatermass And The Pit. Wisely, rather than understandably opting for the sort of hallucinogenic puffins that they were reimagined as for the big screen adaptation, the illustrators wisely elected to base their interpretation on the original 1958 models, responsible of course for one of the simplest yet most effective jump scares in television history when one of them apparently ‘moves’ as a torch is shined on it. They were of course shaded green for the book cover in the absence of any colour reference material when the originals where apparently a sort of sandy beige, but this mishued reappearance appears to have been more than a little convenient for whoever was designing spinny-eyed antagonists The Foamasi for The Leisure Hive a couple of months later, as they are to all intents and purposes exactly the same. Still, even in the midst of all this mildly confused looking back to the sci-fi of yesteryear, Doctor Who itself was very much fixated on the exciting new age of the silicon chip…

Step Into The 80s!

Founded in Massachusetts in 1972 with a stated business strategy of putting ‘Software First’, Prime Computer Inc. were early leaders in the burgeoning microcomputer market, specialising in sleek yet high-powered business models that looked less like set dressing from a late seventies sci-fi film than they did a high-end MFI suite; even the requisite in-built spool of tape looked unaccountably stylish. In 1979, they had broken new ground with the ’50’ series, carefully designed to meet the requirements of academic institutions, with range leader the Prime 750 – an early 32-bit system – boasting an impressive 8Mb of RAM, 1200Mb available storage space and a 9-Track tape unit. With the increasingly microchip-fixated world at their variable-processing feet, what better way to promote their wares than with a series of adverts featuring an at best semi-in character Tom Baker and Lalla Ward getting to grips with a computer that average television-watching punters had little to no interest in or practical use for, and which were only shown in Australia anyway? Quite what degree of market saturation they inspired is another question entirely, but lucky viewers in the land down under were nonetheless treated to a series of whimsical Prime-promoting Doctor Who mini-adventures in all but name, complete with a sort of whoinging mock-‘TARDIS’ sound effect and music that sounded more like it belonged in the Quatermass revival, with The Doctor and Romana employing the assistance of a nearby Prime 750 – which they had, crucially, ‘seen on Gallifrey’ – in obtaining the orbital co-ordinates of nine hundred planets in the constellation of Kasterborous in seventeen seconds and calculating the total length of The Doctor’s scarf – 7.013 metres exclusive of the loose threads, in case you were wondering – while marvelling at its seven languages and five protocols, earning them an unamused rebuke to ‘don’t patronise me Doctor’ for their silicon chip-dazzled troubles, and even ultimately requesting relationship advice from the hapless oversized integer-tackler, prompting an impatient suggestion to ‘MARRY THE GIRL DOCTOR’. Considering how that would work out for all concerned in reality, perhaps this was the moment at which the industry at large should have begun to question Prime’s computational accuracy. In certain other regards, however, Prime’s calculations would prove to be uncannily if unintentionally accurate. Having, well, stepped into the eighties with considerable fanfare surrounding their skilled integration of cutting edge technology, Prime would to struggle to maintain this momentum as the decade progressed, frequently unwisely opting for endorsing riskier technological advances whilst losing ground to smaller-scale competitors that may not have been as far-thinkingly sophisticated but used the means at their disposal to a more immediate mass appeal-courting effect, before being quietly ‘retired’ – without any official acknowledgement that it had been – as the nineties arrived. What is more, it did so without any assistance from Terror Of The Vervoids too.

“I Know Who You Are!”

Poor old Meglos seemingly never could get anything right. The title was changed during production from The Last Zolfa-Thuran – a title dripping with the promise of intrigue, mystery, urgency and pathos – to Meglos, which sounds like exactly the sort of name you would give to a story about a talking cactus. Written explicitly with the contrast between studio and location work in mind as a narrative device, budgetary considerations instead resulted in it being realised entirely in the studio with virtually no amendment to the scripts whatsoever, and to say that it looked like it would be generous to say the least. Widely hailed by fan writers as featuring pioneering if not the actual first ever use of Scene-Sync, an effect allowing two separate cameras to move in unison so that live actors could be convincingly superimposed on a moving backdrop, it was in fact nothing of the sort; Scene-Sync had been in use at the BBC for several years by that point, and in fact the myth-embellishing The Scene-Sync Story on the Meglos DVD opens with clearly marked studio floor plans for the BBC’s ‘Sunday Classics’ adaptation of Pinocchio from 1978. Even the new theme music is played in at the wrong pitch on one episode. There was, however, something that Meglos did get, well, ‘Wright’. After leaving Doctor Who early in 1966, Jacqueline Hill, one of the original stars of the series at a time when it very nearly rivalled The Beatles for popularity, had – as would prove to be the case with so many of her contemporaries – taken a step back from public life to start a family, and would soon find herself all but forgotten by audiences and by the industry alike. Fortunately for Jacqueline, she happened to have started that family with acclaimed director Alvin Rakoff, and once enough time had passed for her to consider a return to board-treading, he cast her as Lady Capulet in Romeo And Juliet, 1978’s opening instalment in the BBC’s prestigious and ambitious attempt to televise the complete works of William Shakespeare, unwittingly providing a private thrill of recognition for the scattered handfuls of Doctor Who fans prevailed upon to watch the production at school over the following decade. Roles in Crown Court, Tales Of The Unexpected and Angels would soon follow, and in 1980 director Terence Dudley suggested her for the role of Lexa in Meglos. Aware of the positive attention that this would be liable to draw from Doctor Who‘s burgeoning and increasingly voluble organised fandom, JNT enthusiastically agreed, and with an uncharacteristic display of restraint made no attempt whatsoever to in any way link Lexa with Barbara Wright; an example that has apparently mercifully been followed by subsequent production teams and spinoff media too. The Dodecahedron still looks like, well, a dodecahedron though. Sorry Meglos. You just can’t win.

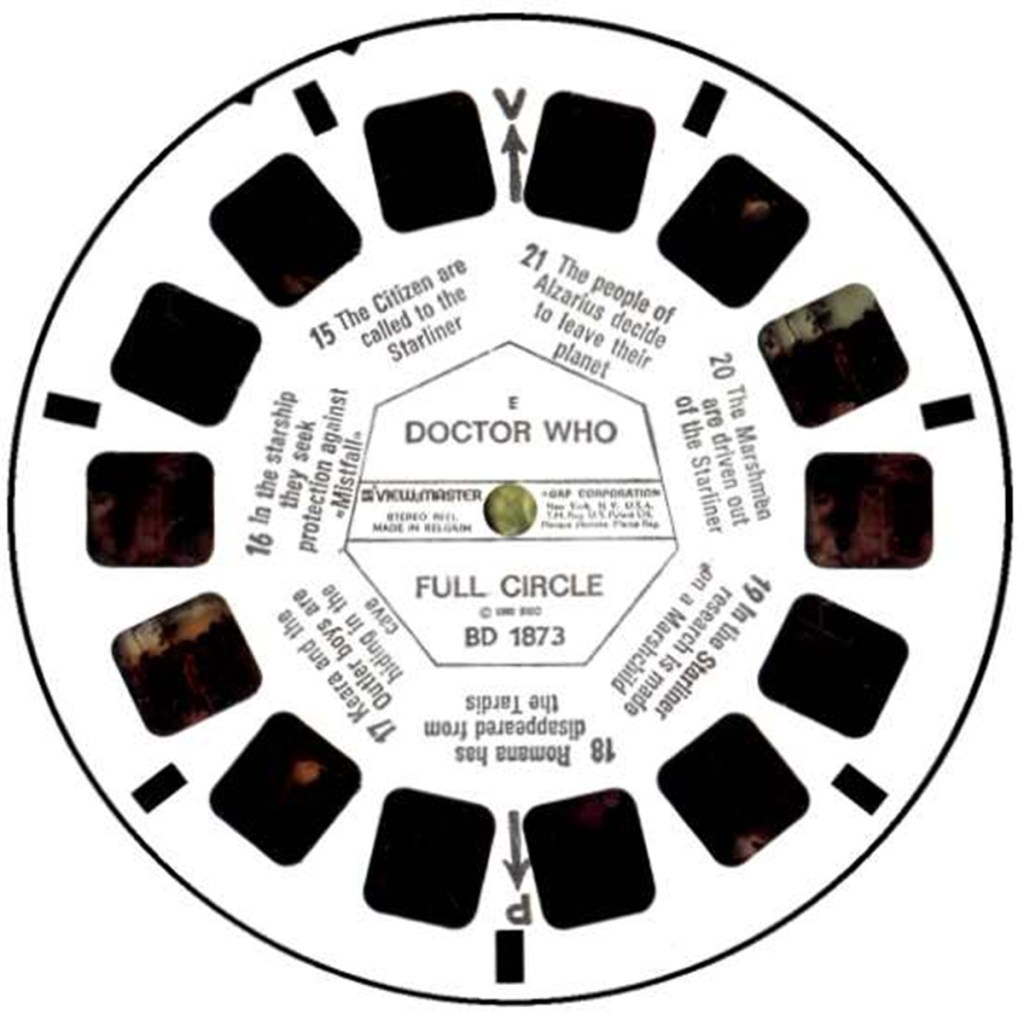

16. In The Starship They Seek Protection Against “Mistfall”

It is only really when you actually find yourself having to consider just how many changes John Nathan-Turner implemented on his arrival as producer of Doctor Who, and indeed how substantial and fundamental they were – and we haven’t even touched on the most significant and impactful one yet – that you realise that even just considering them in passing leaves so little space for any further consideration of a series that you had not only thought there would be plenty of angular observations and gags to make about but also are often minded to consider may well be your favourite run of Doctor Who of all. Scribbled notes suggesting entries on Tom Baker’s two waxworks, “…especially if I do this!”, the gantries in Warriors’ Gate apparently being lit by the Top Of The Pops production team and even a partially written one about the proliferation of a certain now unfortunate hairstyle in this run of episodes headed Out There In Space, Shall We Find Blokes With Abacuses? have had to be equally hastily scribbled out due to what can only be described as a lack of room. Even aside from there not being sufficient space to properly ruminate over Christopher H. Bidmead’s contribution to Doctor Who‘s relaunch and indeed arguably its long-term future, it is even more difficult still to crowbar in any mention of the fact that Barry Letts was brought in as an executive producer to assist the relatively inexperienced JNT and more than likely had more than a hand in proceedings too. Two longstanding and much-loved regular cast members were phased out in favour of three brand new and notably ‘younger’ characters, yet they may well struggle to secure even a mention in passing. Most naggingly inconveniently, however, the major thematic narrative diversion of this run of episodes – an inadvertent extended period spent trapped in ‘E-Space’, an external pocket universe with negative co-ordinates and sort of scouring pad green ‘space’ where the most significant issue at hand is that The Doctor and Romana simply do not want to be there; K9 on the other hand does not appear to be unduly concerned by this turn of events – which looms so large in the reputation of this major repositioning of Doctor Who that it not only inspired a DVD box set entirely of its own but also the actual title of this entry in It’s Still A Police Box, Why Hasn’t It Changed?, has unwittingly yet by necessity taken a back seat to assorted other aspects considered more worthy of blokes on forums-enragingly overlong commentary. The story in which they find themselves adrift amongst a universally external gaggle of four and a bit planets, Full Circle, is in itself possibly more notable for illuminating even more otherwise unacknowledged aspects to John Nathan-Turner’s quiet revolution than it is for its ingenious storyline, surprisingly accomplished realisation which it has to be emphasised stands up unexpectedly well even now, and, well Kenneth Williams’ ‘excitable’ diary entries about it. Serving early notice of a constant determination to discover and encourage new talent that would help to launch the careers of several major talents both behind and in front of the camera, albeit to little wider acknowledgement, Full Circle was commissioned on the basis of a story outline sent in by seventeen-year-old aspirant scriptwriter Andrew Smith, and introduced eighteen-year-old Matthew Waterhouse as incoming TARDIS traveller Adric, whose intentional unpopularity and abrasiveness is perhaps better explored elsewhere at somewhat more substantial length than the umpteenth adjunct in an already very long sentence. While neither Smith nor Waterhouse would go on to exactly enjoy quite the sort of stellar career that they no doubt envisaged in the initial flurry of excitement that accompanied Full Circle – although both would remain very proudly and gratefully associated with Doctor Who – it is fair to say that they made their debut with an impressive and original story which even in itself, with a complexity of observation that Decider Draith would doubtless be impressed by, reveals even further depths to JNT’s under-appreciated vision for a bold new Doctor Who for the eighties. Also present on set and indeed on location was a stills photographer for the General Aniline And Film Corporation assigned to capture stereoscopic images to form the basis of a presentation of Full Circle for View-Master, a once ubiquitous red plastic 3D viewer toy slash novelty that in its heyday churned out thousands upon thousands of reels encompassing everything from intercontinental landmarks and The Smurfs to long-forgotten Keep Britain Tidy mascot ‘Dusty’ and The Waltons for the edification of pre-home video youngsters hungry for home entertainment, and which incidentally you can hear much more about in Looks Unfamiliar here. As quaint as this may seem now, the very idea of Doctor Who aligning with anything as interactive as View-Master – and this was not the only occasion; GAF would return to add some literal depth to Castrovalva the following year – is indicative of JNT’s belief in the potential in a changing technological and media landscape for Doctor Who to continue as a viable entertainment option outside of its allocated broadcast hours, although while several of his attempts to expand the show into other media were a resounding success, others as will become increasingly obvious as the eighties progress simply suggested that he may have had ideas that were years ahead of their time but lacked the self-awareness to realise that implementing them might not be technologically or even practically viable for a good while yet. What’s more, as the dual-angled photographs used for the View-Master reels were effectively unique and now appear not to exist in any other form, they have the unexpected legacy of forcing an amusing quotient of completists into performing disconcerting contortions with magnifying glasses in a bid to ensure that they are ‘best’ at Marsh Spiders. Meanwhile, speaking of both E-Space and expansion into other media…

Wasting The Wasting

It may not have had a stereoscopic photographer hovering about between takes, but the second E-Space set story State Of Decay – as you can find out much more about here – was considered to be in sufficiently close proximity to cross-platform friendliness that it was turned into Doctor Who‘s very first authentic and dedicated audiobook, complete with copyright-averting music that sounded like someone who had never heard of Doctor Who had read a description of the theme music by someone who couldn’t remember how it went, listened to Peter Howell’s Through A Glass Darkly, bought an electronic keyboard from Tandy because they liked the demo tune that the shop assistant had neglected to turn off and then just did more or less whatever they felt like but panicked at the last minute and remembered it had to be about ‘space’ and threw in a disproportionately loud stereo-panning ‘laser’ and hoped for the best. State Of Decay was certainly well liked at the time, and inspired not just an enjoyably brisk and well above average novelisation from Terrance Dicks but indeed that audiobook for which he essentially wrote a whole new separate novelisation, but since then it appears that there has been some kind of meeting that nobody else was invited to – not even Aukon – where it was unanimously decided that State Of Decay was the one to ignore and overlook in a series that included bloody Meglos. This would be baffling enough on account of the quality of the story as broadcast in itself – witty and nerve-jangly in equal measure, with not just K9 being a villager-vexing smartypants to contend with but a freshly stowed-away Adric throwing a spanner at the spanner he’s already thrown into the works by deciding on the basis of stupidity and greed that becoming a space vampire holds greater CV-boosting potential than roaming N-Space past and present with two noseypoke Time Lords and their shooty dog thing, and above all is Doctor Who fighting vampires and frankly to the average self-respecting member of the intended original target audience it simply does not get much better than that – but the bizarre route it took to production is not just fascinating in its own right but should in theory elevate it by association alongside a certain all too over-lauded corner of Doctor Who‘s history that a certain strain of all too prevalent bore insists on measuring more or less anything and everything else against in a tiresomely want-finding manner. The Wasting, as it was originally called when it wasn’t also apparently going under the name of The Vampire Mutations and/or The Witch Lords, was originally to have opened the 1977 run of Doctor Who and despite the strict instructions to incoming producer Graham Williams to tone the furore-provoking excesses down, would certainly have continued the established and widely feted ‘gothic horror’ style in a more acceptable manner. When BBC Head of Serials Graeme McDonald got wind of the Count Dracula’s Deadly Secret-adjacent plans, however, he expressed concern that it might for some frankly incomprehensible reason pre-empt and undermine the BBC’s upcoming flagship adaptation of Count Dracula – which, incidentally, was not a serial – and prevailed upon the production team to shelve Terrance Dicks’ original scripts in favour of his hastily but splendidly written emergency replacement Horror Of Fang Rock, which arguably still to an extent continued the established and widely feted ‘gothic horror’ style in a more acceptable manner but also in one that effectively drew a line under that troublesome era. When a number of writers under consideration failed to deliver anything that was quite workable within the new approach, however, Christopher H. Bidmead was left with little option – and with tremendous irony – other than to reach for the more or less camera-ready scripts sitting around on his desk and that, essentially, is how State Of Decay finally made it to television and indeed audiobook. Count Dracula of course would find itself hailed in many quarters as a superlative and quite possibly definitive adaptation of the original source material. State Of Decay, on the other hand, would find itself hailed as little more than one of those moments when all of those hardy individuals slogging through a story by story Doctor Who rewatch slash review that seemed such an easily accomplishable task when they very first thought it might be a quick and easy and fun distraction fire off a mardy social media post about there being too many episodes and something something pantomime embarrassment. The indisputable fact of the matter, though, is that it is a hugely enjoyable and just the right kind of inconsequential horror-tinged joke-riven runaround with a hugely likeably big dumb conclusion that entirely by accident straddles two of Doctor Who‘s most accomplished and celebrated eras and makes the absolute most of both of them, and most importantly is about Doctor Who fighting vampires, and it really is time it was afforded a little more attention. Yes, even that music from the ‘Talking Book’. Anyway, is that a sort of gateway out of E-Space…?

Black Time White Void

On 11th December 1980 at 13.45pm, BBC1 presented the fourteenth outing of Spaceman, the sixth episode of their much-loved 1971 Watch With Mother show Mr. Benn. This particular expedition through The Door That Could Lead To Adventure saw the bowler-hatted changing room-hopper asking to try on a spacesuit and correspondingly finding himself on a rocket in the company of a disconcertingly generic astronaut on an exploratory mission to several drawback-marred planets including one teeming with precious stones that turned into worthless rocks the moment they left the atmosphere, another where the lively and vibrant surroundings were literally underscored by what appeared to be somebody repeatedly stopping and starting a Keith Tippet Group album at a deafening volume, and most memorably a swanky well-to-do sophisticated city on the move that just happened to be entirely devoid of colour. Three weeks later, the TARDIS found itself precariously perched in a similarly monochromatic void at the very edge of E-Space, and unlike Mr. Benn, Romana and K9 did not find their way back to Festive Road with a previously bejewelled rock in their pockets to help them remember. Which was possibly something to be thankful for on the basis of K9’s likely interminable explanation of the phenomenon alone. John Nathan-Turner had never made any secret of his disdain for the inherited TARDIS stuffed with clever clogs know-alls, hence his decision to replace two incredibly popular characters with the markedly less popular Adric, who was of course, erm, a boy genius who had won a proudly sported gold badge for his achievements in the field of mathematics, but at least he was more liable to wander about pissing people off and pressing the exact wrong button at the exact wrong time for no other reason than that he felt like it. There were of course other factors in play in the decision to retire what many might well argue was the very best assembly of central characters in Doctor Who‘s history – not least Lalla Ward’s turbulent relationship with Tom Baker – and the tabloids inevitably sensed an opportunity to bash the BBC and launched countless ‘Save K9’ campaigns where any sense of awareness of or giving a flying fuck about anything that actually happened within the show itself ended halfway through the headline, but to no avail – the decision had been made and Romana and K9 would voluntarily remain on the other side of a handily positioned Charged Vacuum Emboitement to assist with liberating the subjugated time-sensitive Tharils. To anyone who has never actually seen The Doctor, Romana, K9 and Adric wandering around in what appears to be the same BBC standard ‘White Void’ set as also favoured by the likes of Blue Peter and Ragtime – although sadly they did not encounter Fred Bubble during their coin-flipping meanderings – and indeed the Prime Computers adverts, this quite probably makes it sound as though Stephen Gallagher’s script was an impenetrably dense simultaneous equation of hard scientific theory about potential dimensional travel and the capacity for multiple realities to exist in the same instance. This was certainly a view widely shared amongst the production team at the time – to the extent that John Nathan-Turner would subsequently intervene in original plans for the novelisation to expand on the televised version of events even further – and one that continues to be shared by Doctor Who fans keen to emphasise that they are very good at understanding it unlike those poor deluded fools who like Holby City, but right the way along all of the above appear to have missed the single most important detail; to the actual intended viewing audience at the time, it made perfect sense. Whichever way you interpreted it, Warriors’ Gate was a story about getting from one place to another and you did not need to be a member of a producer-troubling over-booksmarted TARDIS crew – or indeed a very clever fan bashing away at a typewriter or indeed subsequently a forum post in one long unpunctuated sentence that appears to have commenced before it started and to continue after it has finished – to follow it. You certainly didn’t get THAT with Buck Rogers In The 25h Century. Mind you, finding himself back in the ‘normal’ universe with only Adric for surely exceptionally patience-testing company and indeed with knowledge of what was coming next, perhaps The Doctor should have followed Mr. Benn’s example and taken this as a salutary lesson about being careful what you wish for…

“People Have Begun To Think She Was Married To The Statue…”

Originally conceived at least partially as an avenue to prepare viewers for an upcoming surprise – well, a surprise to anyone who had somehow avoided all news coverage, playground and workplace chatter and probably even stray conversations outside Fine Fare – quasi-Ruritanian saga of succession, flimsy peacekeeping protocols and sort of stone statues with helter skelter faces The Keeper Of Traken would itself prove something of a wealth of surprises; one enormous one for the audience which we will be coming to in due course, and even then taking the production team by surprise as they were so taken with The Moon Stallion – which you can find much more about here – alumnus Sarah Sutton’s Swap Shop-courting portrayal of fizzy-wigged aristocrat Nyssa that they elected to hastily retain her as a regular character. A sturdy and thought-provoking story much more in line with traditional Doctor Who than the assorted fretting over backblast backlashes and dodecahedrons that had preceded it, The Keeper Of Traken is nonetheless notorious for one particular explicability-defying outburst of silliness. As Nyssa’s father and Keeper nominate Counsul Tremas ties the knot with more easily manipulable fellow Consul Kassia – thereby setting the entire Melkur Switcheroo-skewed, well, master plan in motion – their revels are accompanied by a quite extraordinary piece of music that sounds for all the world like an unstoppable jester is running production-haltingly amok on the set of Jackanory Playhouse, veering suspiciously close to a companion piece to the music from the Talking Book of State Of Decay and heavily suggesting that even Roger Limb may well have been listening to Through A Glass Darkly by Peter Howell. Subsequently afforded full-length pride of place on the original Doctor Who – The Music, it would later prove a hazardously unshiftable earworm for a generation of Doctor Who fans sitting school exams with questions that looked like one of Christopher H. Bidmead’s story briefs, and later still social media would find itself abuzz with videos of fan-inclined couples who had exchanged I Dos to the accompaniment of that very piece of music, hopefully with a congregation of Ftone Clearers on hand to remove any rogue statues that might have taken it as their honking Answer Prancer-esque clarion call. We can only hope that they had neglected to invite the reason behind those rocky interlopers…

“Peoples Of The Universe, Please Attend Carefully…”

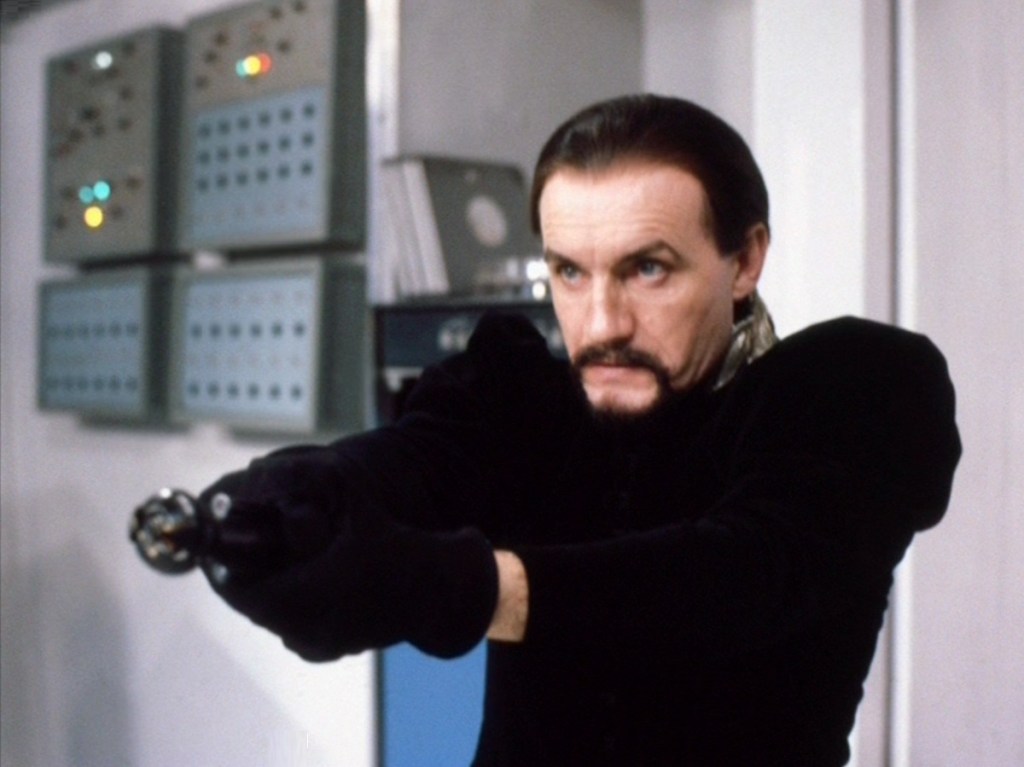

When audiences last caught sight of The Master in The Deadly Assassin – as you can find out more about here – he had run out of regeneration energy and had effectively assumed the form of an angler given to dossing down for the night in a pile of rotting fish with even more rotting fish being dumped onto him on a prompt hourly basis; all things considered, it was perhaps no real surprise that he did not succeed in his bid to secure himself a further stash of regenerations. By the time that the eighties rolled around, the Doctor’s one-time arch-nemesis was to all intents and purposes as good as a forgotten adversary, so few can really have been expecting him to reappear in The Keeper Of Traken, still in search of that elusive restorative cache of regenerations and having at least upgraded his appearance to that of someone who preferred month-old contents of a salad tray to actual proper clothes. Even in a run of stories crammed full of technobabble like a machine code program listing in an issue of Sinclair User the logic behind The Master being able to assume Tremas’ physical form by virtue of him having rested his hand against his grandfather clock-cosplaying TARDIS is honestly just left as it is on face value, though the identity of the actor playing both variously-bearded iterations of the same character serves as yet further evidence that the new producer had assumed responsibility for Doctor Who with a plan already in place. John Nathan-Turner had first encountered Anthony Ainley, an experienced and reliable supporting actor, on the set of the BBC’s celebrated 1974 adaptation of The Pallisers in which he played – as Doctor Who Magazine was always wont to remind us – ‘Smarmy Emelius’. Whether or not he detected a hint of The Master about him on their first meeting is sadly a matter of speculation, but the fact of the matter is that when JNT astutely sensed that the moment was right for The Doctor’s arch-nemesis to make a return, there was no doubt from his perspective as to who should play him. Adding a powerful dash of last-minute menace with a studied performance that imbued the character with an extra sense of being slightly yet dangerously detached from everyone else’s reality, it is difficult to convey from this distance just what an impact Anthony Ainley made on his debut as The Master, and indeed why an entire generation would experience such a rush of excitement when his laugh issued from a previously innocuous-looking pocket watch many years later. Unfortunately, part of the reason for this difficulty in conveyance was that – proving the old adage that you can have too much of a good thing – he would wind up being staggeringly overused, often with no real good reason to be in any given story and invariably with his appearance ‘disguised’ with a ‘clever’ pseudonymous name like Het Remsat and a entirely convincing fake moustache added on top of his already extant entirely convincing fake moustache. This, it has to be said, was not entirely helped by the fact that Ainley reputedly grew so attached to The Master that he refused to play any other character in anything else, nor indeed that one of the handful of other engagements he did deign to take on was singing – sort of – “AND THE CAYNINE COMPYOUTARRRRR” on a charity record nobody asked for. All of the initial excitement, promise and exhilaration of much-needed change was lost in a lengthily drawn-out flurry of welcome-overstaying, to the extent that it is now difficult to convince anyone that it was ever otherwise, and if there is a better analogue for the wider implications of John Nathan-Turner’s tenure at the helm of Doctor Who then frankly one has yet to present itself. After all, he did take a decision that few if any other producers would have dared to…

The Moment Has Been Prepared For

By 1980, Tom Baker had been Doctor Who for six years, six series and – if Shada had not been abandoned due to industrial action – what should in theory have been over one hundred and fifty episodes; more than sixty hours of screen time, and that is not even taking into account the innumerable appearances he was prevailed upon to make in costume and in character, many of which were not even intended for television in any sense whatsoever. It is entirely possible that, at least as far as the general public were concerned at that particular moment in time, he was the most deeply associated that any performer has ever been with the part, and anyone born within the past decade more than likely had little to no idea that anyone else had ever played The Doctor. In reality, however, by that point he was quite possibly the least invested in the part that any performer has ever been – well, maybe with one exception, but let’s not get into that right now – and was worn down, ill-tempered, creatively dissatisfied and frightened to relinquish a role he nonetheless longed to move on from. One notorious manifestation of this dissatisfaction was a tendency to threaten to quit if he did not get his own way with directors who did not share his creative vision, invariably necessitating panic from the production office and more often than not intervention from higher up at the BBC. To pretty much everyone else, Doctor Who without Tom Baker seemed pretty much unthinkable, yet the very first time he pulled this stunt under John Nathan-Turner’s tenure, the response came back that maybe it was indeed time that he should think about leaving. Baker would later warmly reflect on the impact of a rare instance of someone in the industry standing up to him and the reminder it served to him of the need to seek new challenges – it is worth noting that for much of the eighties, he found himself uneasily flitting between all-too-‘Doctorish’ engagements such as playing Sherlock Holmes in the BBC’s ‘Sunday Classics’ adaptation of The Hound Of The Baskervilles and narrating The Iron Man for Jackanory and consciously different roles in the likes of The Life And Loves Of A She-Devil and Blackadder II that he was careful to advise everyone ‘might come as a surprise’ to anyone who associated him primarily with Doctor Who, and staying even a year longer would have made that typecast straitjacket even more difficult to escape from – and for all that conventional wisdom may contend that he ‘enjoyed’ a fractious relationship with JNT, they certainly seemed to enjoy messing around with the press whilst announcing his departure, notably with a throwaway suggestion that the next Doctor would be a woman which it later transpired both had been privately entirely serious about. What was more, JNT’s skill at dealing with and distracting reporters saw to it that the news was greeted with more of a fond farewell and a curiosity about who would come next than any sort of an outcry. Accounts seem to vary on whether his intention had been to replace Tom Baker from the outset, but if it really did effectively happen in that instant then his efforts should be applauded and appreciated all the more. Evidently those concerns about the opening titles were not arrived at on a whim after all.

Logopolis, the very last of Tom Baker’s seven years, seven series and by now over one hundred and seventy episodes and seventy hours in the lead role of Doctor Who, could scarcely be described as a fond farewell. It opens with the sound of the TARDIS warning system the Cloister Bell and a pensive and pessimistic Doctor planning drastic displacement activity in the form of finally repairing that Police Box-favouring Chameleon Circuit. Before too long he and Adric are obliged to make their way through an infinite procession of dingily lit Console Rooms whilst The Master casually murders passers-by on a grim-looking hard shoulder before his attempts to interfere with The Doctor’s plans by doing likewise with a planet full of mathematicians inadvertently threaten to erode the Universe in a welter of entropy. Unsurprisingly, The Master deduces a way in which he can turn this to his peoples of the universe-ransoming advantage, causing The Doctor to regeneration-triggeringly plummet from a radio telescope in a noble but undignified manner. Beset by visions of some of his former fellow TARDIS travellers looking never less than desperately glum and an assortment of adversaries apparently practicing ventriloquism and accompanied by some of Paddy Kingsland’s finest downbeat meanderings, the Fourth Doctor bows out with a decided lack of fanfare, and right throughout there’s been a mysterious spectral figure standing at a distance and ominously observing. With plans to reintroduce some of his earlier companions to soften the blow for the audience having fallen through, John Nathan-Turner instead literally surrounded him with those three new young faces – gobby Australian air hostess Tegan Jovanka was always part of the plan for this story, and Nyssa was very cleverly and carefully worked into the plot rather than just being awkwardly inserted into the action – but even they fail to add much mirth to proceedings, even being berated by The Doctor partway into the story for having barged in on his escapades for their various own individual advantage. The only smile that is really cracked throughout the whole of Logopolis – and there can be little doubt that this was a deliberate move to provide a more effective contrast to the forward-looking positivity of the arrival of a new lead actor – is that of the face of the immensely likeable and infinitely cheerful incoming new Doctor. He was also someone whom John Nathan-Turner had worked with before – and the very first that viewers would get to see of him was wishing them a Merry Christmas…

Anyway join us again next time for the worst Butterkist endorsement in popcorn history, Dirk Benedict and a Cylon vying for audience attention with a dry stone wall and the unexpected Aunt Lavinia/Hi-NRG crossover…

Buy A Book!

There’s lots more about Peter Howell’s overhaul of the Doctor Who theme – and plenty more about other of BBC Radiophonic Workshop projects besides – in Top Of The Box, the story behind every single released by BBC Records And Tapes. Top Of The Box is available in paperback here or from the Kindle Store here.

Alternately, if you’re just feeling generous, you can buy me a coffee here. I really don’t recommend walking along Brighton Beach for one.

Further Reading

You can find more about some happier times for The Doctor, K9 and Romana in It’s Still A Police Box, Why Hasn’t It Changed? Part Eighteen: Erato, Erato, Put Your Hands All Over My Body here, and there’s also another look at State Of Decay‘s unusual prominence in other media in I Can Hear That Sound Again here.

Further Listening

You can find out exactly why I loved the Talking Book of State Of Decay so much – and just how much of it I can recite word for word – in Doctor Who And The Looks Unfamiliar here.

© Tim Worthington.

Please don’t copy this only with more italics and exclamation marks.