It’s probably fair to say that State Of Decay is not exactly the most highly regarded story from Doctor Who‘s big updated modernised relaunch series – which also, not entirely coincidentally, happened to be Tom Baker’s final one – but it is equally fair to say that this is to some extent a retrospective viewpoint imposed by an audience that it was not strictly originally intended for. If you were a very young viewer in 1980 who was already dazzled by the brand spanking new opening titles and theme music arrangement and the sub-narrative diversion about being stranded in a miniature universe, the idea of Doctor Who, Romana and K9 fighting vampires with Classic Horror stylings given an intergalactic twist seemed like quite simply the best thing ever. It’s hardly surprising, then, that despite its overlooked status State Of Decay still holds a place deep in the affections of those who watched it under similar circumstances, and indeed that I not only read and re-read the Target Books novelisation of State Of Decay but also repeatedly listened to a double cassette set of Tom Baker reading out an entirely different adaptation of the story bookended by compellingly and hilariously ridiculous music, which at that point was essentially the closest that the overwhelming majority could get to actually ‘watching’ Doctor Who when it wasn’t on the air. Perhaps an indication that back then, with limited options and similarly limited technology, we appreciated home entertainment on a more simple and straightforward level. This was originally written in a much longer form – with much more on the history of the Pickwick Talking Books imprint, the technical development of commercially available synthesisers at the turn of the eighties, the story behind various actual adaptations of The White Ship, what actually went on with the BBC’s Count Dracula and a competing big screen version that apparently somehow escaped their attention despite both productions sharing cast members and plenty more besides – as a new feature for my anthology Keep Left, Swipe Right, and you can find that extended version in paperback here or at the Kindle Store here.

In the autumn of 1980, after a couple of years of mixed fortunes to say the least, Doctor Who started to find itself just as Doctor Who himself got very lost indeed.

Launched with a synthesised trumpet fanfare of publicity and the first episode of The Leisure Hive on 30th August 1980, the eighteenth series of Doctor Who – Tom Baker’s final run in the title role – was conceived from the outset as very much a new show for a new decade; not unlike, in a neat coincidence of seventies-bookending symmetry, Jon Pertwee’s debut a decade earlier. Brought in with a brief to modernise and revitalise Doctor Who following a turbulent late seventies that had seen it roundly condemned initially for being too horrific and then for being too silly, incoming producer John Nathan-Turner took an immediate decision to replace the graphics, the music and even the regular cast with something more attuned to exciting new modern tastes. Longstanding soundtrack composer Dudley Simpson was quietly informed that his ominously descending brass stings were no longer what the cliffhangers demanded, and the compositional duties were instead handed over to Paddy Kingsland, Peter Howell, Roger Limb, Elizabeth Parker and the many other Fairlight CMI-friendly synth wizards at the BBC Radiophonic Workshop. Howell, who was very much viewed by BBC Records And Tapes as their own in-house budget-conscious counterpart to Jean-Michel Jarre and Vangelis at the time, was also tasked with updating the theme music – which at that point was technically still Delia Derbyshire’s original recording from 1963, although by then it had been subjected to so many edits and additional enhancements that even Mehendri Solon would have advised them to steady on a bit – with a new arrangement built up from sequencers, voice modulation and MIDI-controlled guitars that felt and sounded ever so slightly more in step with the post-punk futurist electronic eighties, while the long-serving ‘time tunnel’ titles were replaced with a racing starfield straight out of the video age and a new neon tubing-inspired logo straight off the cover of a pre-cert video.

With little willingness or patience to indulge Tom Baker’s by now legendary production-souringly jadedness and irritability, John Nathan-Turner also somehow managed to pull off the unthinkable and persuaded him that the time might be right to leave the series and hand over the role to a younger actor; a decision that was not only arrived at amicably but also earned him the perpetual warm-hearted professional respect of the not exactly famously casually cordial Baker. At the same time, feeling that the show had come to rely too heavily on undergraduate-level humour and the day being conveniently saved by a laser-blasting robot dog in lieu of a proper ending with any degree of ingenuity, and an associated tendency to leave viewers feeling left out and cheated respectively, Nathan-Turner also elected to write out well-established fellow TARDIS travellers Romana and K9 and their bookish witticisms. In their place came a gaggle of naïve and arrogant teenage strop-throwers and – significantly – a determined drive towards stories with a more Fractional Quantum Hall Effect-aligned grounding in the sort of modern popular scientific theory that primetime BBC audiences might normally have seen being explained in viewer-friendly terms on shows like Tomorrow’s World and Horizon. The sort of changes, it has to be said, that are pretty much guaranteed to provoke a certain type of viewer into fuming with incandescent rage about how this is all an insult to the classic days of timeless magic and nobody asked for this cheapening pandering to a ‘trendy’ audience who could never possibly understand what it was like to have drawn Bellal in a Silvine Exercise Book. If you were a much younger viewer who got excited when New Musik turned up on Swap Shop playing synthesisers, coveted ‘a go’ on any given calculator and made secret detailed operational plans to be enacted in the event that you woke up to find Big Trak at the bottom of your pillowcase on December 25th, however, it was exactly what you wanted and more, and sometimes that’s the most important reaction there is.

Part of this reinvention-occasioned diversion involved a literal diversion as, for a whole three stories, The Doctor, Romana and K9 found themselves trapped in ‘E-Space’ – a pocket universe with negative temporal-spatial co-ordinates that had formed on the outside of our own – with little obvious hope of finding their way back out again. Full Circle – written by Andrew Smith, a seventeen-year-old fan who had submitted an atypically strong story breakdown to the production office; although his insistence on involving fans in Doctor Who’s actual production would later cause him no end of headaches, John Nathan-Turner’s active encouragement of the various writers, artists, musicians and others who had been inspired towards creativity through their love of the show to try their hand on a more professional level is something that he is never really given enough credit for – was set on a planet caught in a hyper-advanced evolutionary cycle that was too rapid for the indigenous species to see coming, and introduced new regular character Adric, a vain and selfish high-flying scholar turned wannabe outlaw who stowed away on the TARDIS at the end of the story out of sheer entitled nosiness. The concluding instalment Warriors‘ Gate, written by up and coming sci-fi novelist Stephen Gallagher, was set in a colour-drained void between E-Space and our own universe where conventional notions of time and space hold no meaning; the fact that it also saved a great deal on scenery costs into the bargain was presumably an inadvertent coincidence. Meanwhile, the story that came between the two was comparatively positively ancient, had evolved imperceptibly over time, and seemed to have a pronounced aversion to sunlight.

Written by former Doctor Who script editor Terrance Dicks – who perhaps fittingly had also been heavily involved with the 1970 relaunch – The Witch Lords, or as it was also known at various points The Wasting and The Vampire Mutation, had originally been intended as the opening story of series fifteen in 1977. It was all set to go before the cameras when disconcertingly late in the day, in one of those bafflingly eccentric leaps of admin that was only really ever possible at the BBC and even then only in the days before John Birt started insisting that every middle manager should have their own middle manager and that everybody used the same three types of teabags or something, word came from on high that these vampires were to stop mutating with immediate effect. BBC2 were planning a high profile adaptation of Count Dracula as the centrepiece of their Christmas schedule, and Head Of Serials Graeme MacDonald had somehow managed to arrive at the conclusion that the expected hordes of Roses-scoffing viewers would be left rolling around in the wrapping paper with helpless mocking laughter at the antics of literature’s most celebrated Witch Lord if silly old Doctor Who with its rubber walls and cardboard monsters had been trifling around with vampires only three whole months beforehand. Despite the frankly baffling nature of his concerns, nobody could apparently persuade him otherwise; production was halted and The Wasting was left, well, wasting. Dicks very quickly came up with Horror Of Fang Rock, a replacement murder mystery set in a 1900s lighthouse that presumably did not pose any risk of potentially undermining any planned adaptations of H.P. Lovecraft’s The White Ship, and the shelved four-parter was quietly forgotten about. Until John Nathan-Turner needed a workable story at short notice after a procession of writers had failed to fully grasp the direction he was trying to move Doctor Who in, and was somewhat relieved to find a more or less ready-made one sitting around on his desk minding its own business.

State Of Decay – as it would ultimately find itself being called after a good deal of debate and disagreement – had to be substantially restructured to introduce not only Adric and the concept of E-Space but also K9, who had not even been so much as a throwaway line in a draft script back when The Doctor and Leela were scouring Fang Rock for an errant Rutan. Filmed in May 1980, when the production team found themselves having to contend with the unexpected additional complication that the stormily romantically involved Tom Baker and Lalla Ward were not speaking and that neither of them had exactly taken to the newly installed Matthew Waterhouse, the story was eventually broadcast in four parts between 22nd November and 13th December 1980, where it presumably did not pose any reputational issues for the Starsky And Hutch episode Vampire. A story about a medieval community ruled over by three similarly E-Space-marooned astronauts who have evolved – or devolved, whichever way around it is – into powerful bat-supported vampires but whose existence conceals a deeper and darker menace and some typically morally debatable historical actions by the Time Lords, it can be argued that State Of Decay has little in common with the more space shuttle-adjacent silicon chip-worshipping stories that surrounded it, and in many ways was more closely aligned with that brief but massively popular detour into classic horror that had caused so much consternation way back when it was originally supposed to have been broadcast, but to youngsters subsisting on a diet of Trebor Mummies while refusing to put down Misty comic, this was scarcely an issue. In fact if anything, its positioning somewhere between Hammer Films Productions’ just slightly out of time stylings and brand new up to the minute sci-fi thrills that you could probably have set your digital watch by if you could actually work out how to use it pushed it far closer to the then-current trends in actual juvenile scare-occasioning horror movies. Well, closer than Count Dracula had managed at any rate.

However much in the way of illicit vampiric thrill it may have engendered at the time, though, nowadays State Of Decay is one of the Doctor Who stories that nobody ever really much comments on one way or the other – a situation that was not exactly helped by the high quality of the stories that followed, especially once they emerged from E-Space into an Art Deco regal power struggle for the scrolling LED display age that culminated in the shock return of The Master, followed by Tom Baker handing over to Peter Davison in an ominous tale of remote radio telescopes, figures watching from flyovers and a regeneration triggered by some very difficult algebra – but to the right audience at the right time it was a fun, entertaining and just about acceptably scary story that perhaps deserves a little more respect than it seems to ever get now. If you want evidence for an assertion that The Three Who Rule did actually rule, then look no further than just how unusually heavily State Of Decay was made available through other media at a time when actual repeats were a rare enough luxury, let alone the opportunity to watch any given Doctor Who story at any given time on any given electronic device. Having written forty two of the sixty four Doctor Who novelisations published by Target Books so far, famously taking up entire shelves in the children’s sections of local libraries entirely by himself, Terrance Dicks was inevitably engaged to rework his own scripts into Doctor Who And The State Of Decay in November 1981, adding a humorous and effective postscript as well as taking the opportunity to indulge in his usual literary mischief with phrases like “it was as though they weren’t quite human” and the gleefully spectacularly over-the-top description of the space vampires finally crumbling into bloodsucking dust, which would certainly have provided the requisite grisly thrills for anyone who was still sulking about not being allowed to stay up to watch The Hammer House Of Horror. Unusually, however, this wasn’t actually the first adaptation that he had written of State Of Decay.

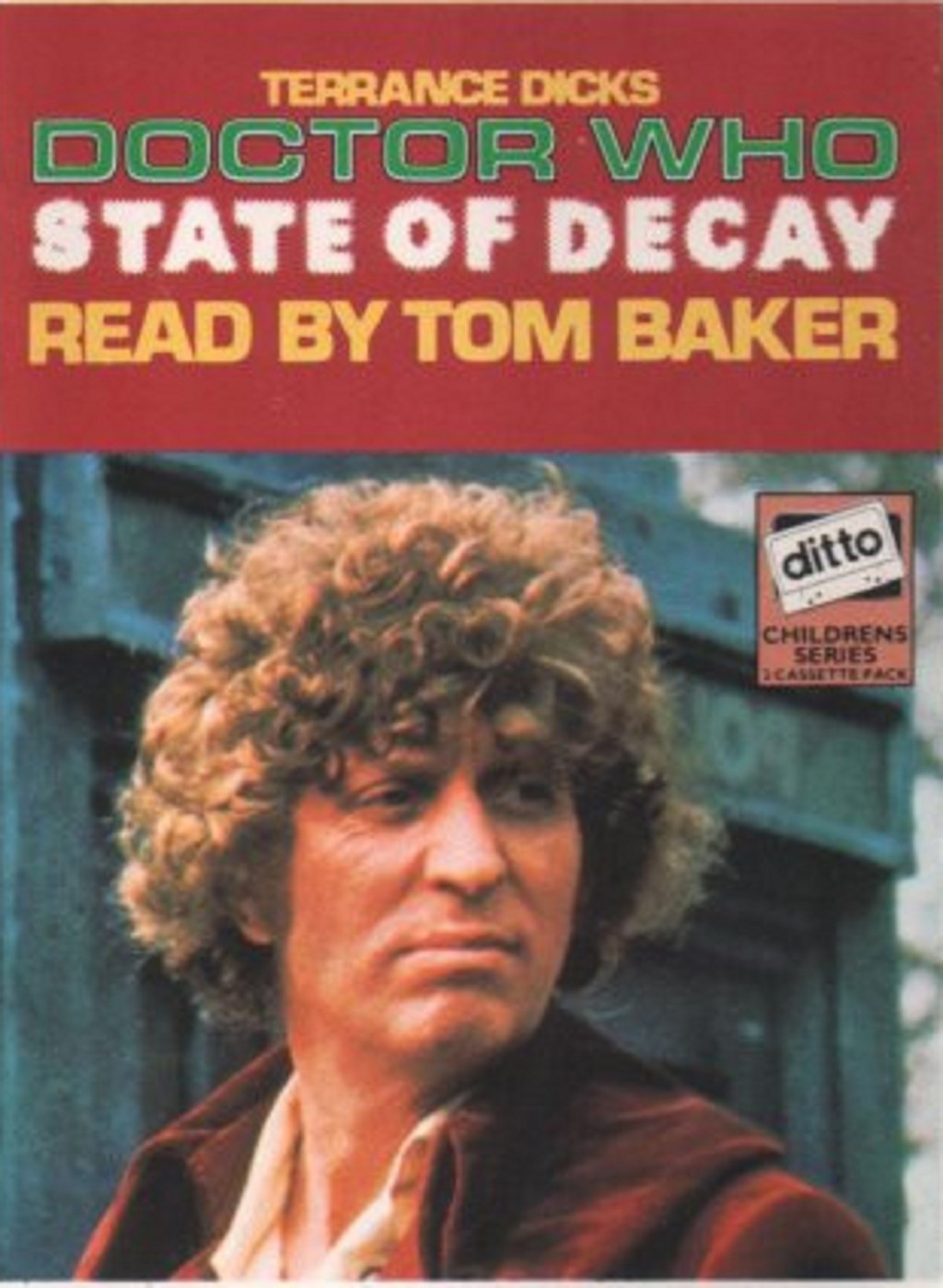

For reasons that are irretrievably lost in an inaccessible external universe, although almost certainly had something to do with it being a good scary story by a writer with a proven track record in children’s literature, Pickwick International approached Terrance Dicks early in 1981 with a view to producing an adaptation of State Of Decay for their recently launched Pickwick Talking Books range, alongside such other literary delights reconfigured for long journey listening as Roy Kinnear reading Roald Dahl’s The Twits, John Hurt reading Dr. Jekyll And Mr. Hyde, Richard Briers reading a selection of Noddy Stories, Miriam Margolyes very specifically reading Walt Disney’s Snow White and the somewhat less dulcet tones of football manager Terry Venables narrating his way through a handful of novels featuring his down-at-heel detective James Hazell. Read in the objective third person by Tom Baker, this completely different retelling of State Of Decay actually changes a number of plot details both major and incidental to suit its medium and method of delivery; notably The Doctor and Romana’s first encounter with a villager is entirely different, as is the reason for Romana cutting her hand and attracting the less than wholesome attention of The Three Who Rule, while there is also a lot more walking and a lot less in the way of references to The Record Of Rassilon. It is also considerably more descriptive than the novel in places, and any plot detail that does not directly involve The Doctor or Romana is either amended so that they observe it from a convenient distance or simply written around completely. Divided into two thirty minute instalments on either side of a cassette, it’s sadly unclear how many parents will have caused the tape to ‘accidentally’ chew up after being asked for it in the car for the eighteen thousandth time, but the fact that it would be listened to over and over again is what is really important here. At a time when the first Doctor Who home video release was still over two years away, and the first affordable one four years further away from that, State Of Decay was – staggeringly – only the third Doctor Who television story to find an audio release after Genesis Of The Daleks in 1979 and a lone episode of The Chase in 1965. Someone at Pickwick must have really, really liked Ivo and Kalmar.

The Talking Book of Doctor Who: State Of Decay – read by Doctor Who‘s most popular and identifiable lead actor around six months after he had left the role, inadvertently capturing a revealing tone somewhere between fondness and detachment rarely found elsewhere – was essentially as close as you could get to ‘owning’ actual television Doctor Who and enjoying it at your leisure, and it was widely loved for that reason above all others; something that it is worth bearing in mind the next time that you feel like very loudly voicing your disproportionately venomous frustration that Doom’s Day isn’t aimed at you personally and worse still has one of those ‘women’ they have now in it too. Correspondingly it sold in enormous quantities, to the extent that it was reissued in 1985 by Pickwick’s budget imprint Ditto where it joined the audio-only escapades of such then-current popular toy-television crossover hit franchises as Transformers, He-Man And The Masters Of The Universe and Rainbow Brite, although sadly we never did discover who would ‘win’ out of Aukon and Mer-Man. Ditto – as the name sort of doesn’t actually imply in any manner whatsoever when you think about it – was a range made up exclusively of double-cassette packs, so for this reissue State Of Decay was edited into four fifteen-minute parts with music added to the start and end of each side. Not the Doctor Who theme, though, or even anything that sounded even halfway like a vague approximation of it. This was literally marching to its own tune.

Kicking off with a synthesised trumpet fanfare that sounds like the parrot playing it has just realised that it’s coming in a quarter of a bar late, a band of session musicians who are evidently not that concerned about sounding like one blast their way through a triumphant pop-rock melody signposting adventure, thrills and spills and derring-do ahead before diverting into a moodier ‘mystery’ interlude with menacing electric guitar drones, synthesised spooky percussion and what appears to be an amplified book being unsuccessfully snapped shut before an extremely loud ray gun effect scorches its way from left speaker to right speaker and pretty much obliterates everything in its musical path. It then returns to the main melody and fades out just as Tom Baker starts speaking, only to fade back in at the end of each instalment before coming to a halt with an ending that very much suggests that everyone involved had one eye on the clock. Kassia’s Wedding Music it was most certainly not.

Except that, in a sense, it wasn’t as far removed from the new and improved music from the new and improved Doctor Who as that might suggest. It may not sound very much like the Doctor Who theme, but the synthesised brass tones and cursory attempts at treated guitar atmospherics are at the very least close enough to Peter Howell’s arrangement to suggest that either someone had been paying attention or it was the most almighty coincidence in the entire history of music composed and recorded to order. It’s difficult to say for certain, however, as there is no way of finding out who composed it to order and why as there appear to be no musical credits for Doctor Who: State Of Decay available anywhere. Complicating matters further still, while it is routinely and indeed understandably assumed by Doctor Who fans that this must have been standard generic music that Ditto slapped across all of its releases, it actually appears to have only ever been used on Doctor Who: State Of Decay; it’s certainly not on Transformers: Battle For Planet Earth or for that matter First Term At Malory Towers, which deploy their own individual evidently specially-composed setting-appropriate music. By any degree of logical conclusion, it would seem that somebody at some point was asked specifically to come up with some music for a Doctor Who story record that was a bit like Doctor Who music but not quite, and what they came up with was this. Which in all fairness at least sounded closer to it than when a ‘witty’ kid at school sang ‘a BOOOO weee oooooooooo-ah!’ on discovering you owned the State Of Decay Talking Book as a sort of satirical joke.

On television, State Of Decay ended with The Doctor and Romana celebrating the villagers’ hopes for the future while sharing their uncertainty over whether it will ever be possible to escape from E-Space, and bluntly informing Adric that his escape will be even less likely as he will be returned home at the nearest available opportunity. The novel concludes with a significantly expanded version of this exchange, with The Doctor suggesting to the villagers that with those pesky vampires out of the way, they might be better staying where they are likely to remain untroubled by outsiders after all, followed by an amusing closing thought from Kalmar musing that nobody that eccentric could ever be a real scientist. The Talking Book is to all intents and purposes a fusion of the two, only rewritten to suit Tom Baker’s voice and indeed ‘voice’ and ending with a delightfully intoned proclamation that ‘the menace of The Great Vampire was ended forever’. It also ends, of course, with a final blast of that deeply peculiar music. It was never actually the Doctor Who theme, and nor was it even pretending to be, but to an entire generation it sort of actually was. Perhaps we should just pretend it was, but in E-Space.

Buy A Book!

You can find an expanded version of I Can Hear That Sound Again, with much more on late seventies electronic music technology and the story behind the BBC’s prestigious adaptation of Count Dracula, in Keep Left, Swipe Right, available in paperback here or from the Kindle Store here.

Alternately, if you’re just feeling generous, you can buy me a coffee here. Don’t do a Romana and chuck it all over The Doctor’s coat. Well, depending on which version you’re listening to. Or watching. Or reading. However that works exactly.

Further Reading

You can find much more about The Doctor, Romana and K9’s escapades from the previous year – when due to a truly bizarre turn of events they managed to top the television ratings for an entire month – in It’s Still A Police Box, Why Hasn’t It Changed? Part Eighteen: Erato, Erato, Put Your Hands All Over My Body here.

Further Listening

If you want to know exactly what that music sounded like, you can find a chat about Pickwick Talking Books’ Doctor Who: State Of Decay in Doctor Who And The Looks Unfamiliar here.

© Tim Worthington.

Please don’t copy this only with more italics and exclamation marks.